Fury at funeral of Pakistan's assassinated minister

- Published

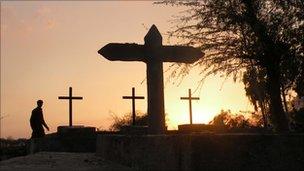

The atmosphere at the funeral of Shahbaz Bhatti, in his predominantly Christian home village, was one of anger and pain

Shahbaz Bhatti's funeral was not the usual, quiet and sombre affair.

There was plenty of sound and fury as members of Pakistan's second largest religious minority, the Christians, mourned the death of their most popular leader.

One of the few remaining voices speaking out against the country's controversial blasphemy laws, Shahbaz Bhatti was silenced when he was shot dead by four gunmen near his mother's residence in Islamabad on Wednesday.

For many in his native village, Khushpur, in the central plains of Punjab - 430km (267 miles) from Islamabad - he was much more than a rare voice.

"He was a symbol of unity not only for the Christians, but for all religious minorities in Pakistan," said his cousin, Francis Lewis.

"For the first time in Pakistan's history, he brought all minorities together to speak with one voice on common issues, and this turned out to be his greatest sin."

Unhappy endings

As we drove down a dusty road into the village, we saw several houses hoisting black flags to mourn his death.

The village of some 10,000 people is predominantly Christian, with a church, several missionary schools and one of the highest literacy rates in the Faisalabad district.

Khushpur - whose name means "the dwelling of the happy" - has had its share of celebrities and their tragic endings.

Shahbaz Bhatti was shot dead near the house of his mother, who travelled to the village for the funeral

As the crowds mourned Mr Bhatti's death in front of his village residence, an old woman among them threw up her arms and started a long, loud wail.

A bystander, a local schoolteacher, told me she was the relative of a former Faisalabad Bishop, John Joseph.

Bishop Joseph shot himself in the head in 1998 when a Christian, Yaqoob Masih, was sentenced to death under the blasphemy law.

"It was the same back then. The entire village mourned when Bishop Joseph's body was brought home. But then there was hope. Now the situation is more desperate," the schoolteacher said.

Traditionally, human rights groups in Pakistan have strongly supported minority rights and though organised groups of religious fanatics have grown stronger since the 1980s, repeated excesses against members of religious minorities often attracted condemnation.

The campaign to reform the blasphemy law and to prevent its misuse dates from the 1990s. It came closest to fruition this year when the parliament sent a draft amendment bill to a committee for vetting.

But the assassination of one of the most ardent supporters of these reforms, Punjab governor Salman Taseer, in January, scared the most daring liberals of the country into silence.

The government even failed to get the Senate to offer customary condolence prayers for him.

The task was left to the likes of Shahbaz Bhatti - himself a member of the Christian minority and therefore more vulnerable than many others who defended tolerance and religious harmony.

Prime Minister Yousuf Raza Gillani attended a memorial service for Mr Bhatti at an Islamabad church on Friday, but only one mid-ranking leader of the ruling PPP party - to which Mr Bhatti belonged - turned up for his last rites in Khushpur.

Some PPP leaders did accompany Mr Bhatti's body in a helicopter from Islamabad to Khushpur, but left from the helipad, presumably due to security reasons.

Only one religious party was represented at the funeral at his home village and the only representative from the PML-N party, which rules Punjab province, was a junior party member who is a Roman Catholic. Many in Khushpur thought he was there in a personal capacity.

PML-N is considered close to some religious hardline groups operating in Punjab, and has failed to condemn the killing of either Salman Taseer or Shahbaz Bhatti in unequivocal terms.

Several thousand mourners chanted anti-PML-N slogans to express their anger and grief.

There were also hysterical chants of "end the black law" and "Bhatti will live forever".

The funeral prayers were said in a compound adjacent to the village church, amid a din of chants and wails.

'Vacuum'

The current Bishop of Faisalabad, Bishop Joseph Coutts, seemed to touch upon the spirit of the occasion when he explained why the minorities wanted the blasphemy law to be reformed.

Many in Khushpur were angered at the poor turnout of politicians at Mr Bhatti's funeral

"In our religion we do not educate our people to insult God or his prophets… No-one is declared infidel or hypocrite in our cathedrals, and our religious leaders do not issue decrees of death against anyone.

"Our grievance is against the wrong use of this [blasphemy] law. If murderers go to heaven, then what good is the heaven. Pardon me, but we cannot worship a god who rewards murderers," he said.

"Nobody is ready to listen to our argument, or accept our innocence. Shahbaz Bhatti's message is, rid Pakistan of prejudice and hatred so that a culture of mutual respect and tolerance takes root."

When I asked Francis Lewis if there was anyone else in Pakistan who would carry forward Mr Bhatti's mission quite as courageously, he shook his head.

"The young people are angry, and their anger may give us a worthy leader some day. But for some time to come, I see a vacuum."

- Published2 March 2011

- Published14 January 2011

- Published4 January 2011

- Published6 January 2011

- Published7 December 2010

- Published5 January 2011