Misdiagnosis behind Bihar's deadly TB epidemic

- Published

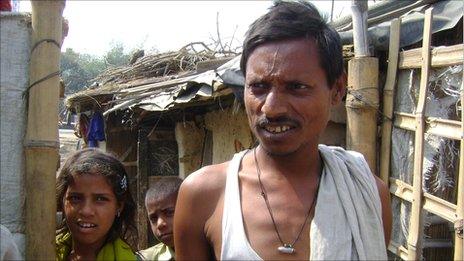

Mohd Noor Alam is among millions of TB patients in India

On World Tuberculosis Day, health officials in the northern Indian state of Bihar are warning of an epidemic of a virulent form of multi drug-resistant TB unless cases are detected more quickly and accurately. The BBC's Geeta Pandey reports from the town of Hajipur, in Bihar, on a disease that kills two Indians every three minutes.

Kishori Rai, 42, looks emaciated and his entire body shakes when he coughs.

He stands in a corner of the dark and dingy hospital room, shifting uneasily from one foot to another, his mouth covered with a white handkerchief which has turned muddy with grime and blood.

When he walked into the District Tuberculosis Centre in Hajipur in Vaishali district, he seemed uncertain that the doctors here would be able to help him.

He tells Dr Ramji Singh that he was first diagnosed with tuberculosis about nine months ago. "I took medicines for six months, but that did not help," he says.

A fortnight ago, he went to a government hospital in the capital, Delhi, where the doctor ordered a sputum culture test to check if he had drug-resistant TB. It's a facility not yet available in Bihar.

It will be another week or two before Mr Rai gets his result. He is told to return with the report before treatment can begin.

"It's difficult to know what happened with him," says Dr Shamim Mannan, medical consultant with the World Health Organisation (WHO).

"It's not known how his TB was diagnosed in the first instance. It's not known what medicines he was given. Maybe he did not even have TB when he was put on medication. Maybe he has now developed multi drug-resistant [MDR] TB," he says.

'Drain on economy'

Day labourer Kishori Rai is a classic TB patient. The search for work takes poor people like him to cities like Delhi where they are forced to live in cramped slums and shanties - a hotbed of infectious diseases like TB.

India gets nearly two million new TB cases every year - the highest in the world - and the disease, which is fully curable, kills at least 280,000 people annually.

"TB is the largest killer of Indians between 15 and 45 years," Dr Mannan says.

In the past decade, India has made major strides in bringing down the numbers of deaths by aggressively following DOTS or "directly observed treatment, short course" - a programme instituted by the WHO where patients must swallow their medicines every day, watched by health workers or volunteers, until they complete their treatment.

But the authorities admit that the disease remains a major public health challenge and an enormous drain on the economy.

And the huge number of drug-resistant cases is threatening to undo the progress made so far - in 2007, India reported 131,000 drug-resistant cases and that number is steadily rising.

'Needle in a haystack'

"In Bihar, doctors are prescribing not just first-line drugs, but also second-line medicines for TB patients," says Dr BK Mishra, head of Bihar's TB programme.

"This will lead to an epidemic of MDR cases which is a very dangerous situation. We will change a drug-sensitive disease into a drug-resistant disease," he says.

Dr Shamim Mannan (left) with TB patients Sanjeev Ram and his wife Pramila in Bihar

Dr Mannan blames the "uninterrupted transmission" of the disease on poor and archaic diagnostic methods used to detect cases.

"For testing TB, we are still dependent on a 100-year-old test called Koch's method which looks for the presence of the disease-causing bacteria in spit," says Dr Sandeep Sen who runs a diagnostic centre in Patna, the Bihar capital.

"If you have a very good microscopist looking through one slide for hours, you get a result that is 50% accurate. It's a very labour-intensive process, it's like looking for a needle in a haystack."

Overall, India has achieved the global target of 70% case detection of TB, but Bihar lags behind at 46% with Vaishali district detecting only 36% of cases.

Poor facilities

The district centre in Hajipur is on the front line of the government's battle against TB, but a visit here does not inspire any confidence.

The laboratory is running low on chemicals and I'm told that the staff are untrained and supplies never arrive on time. In one room I look in, I see a blood-laced coin-sized sputum sample on the floor, next to a plastic cup in which it was perhaps collected.

Geeta Devi is being treated for TB

The poor state of public health facilities forces patients to go to private labs and doctors who routinely prescribe unreliable blood tests known Elisa (enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay).

"Elisa is hopeless. It serves no use," says Dr Mannan. "If I am tested, I will also test positive. So will 500 million Indians. We all have the antibody for TB in our blood, but these are latent infections. It doesn't mean I'm diseased or I need treatment."

Elisa kits are developed by firms based in Australia, Germany, Britain, France and the US, but these kits are not approved for testing TB in those countries.

"But lax Indian laws mean doctors here order these tests and often prescribe strong and toxic TB drugs to patients on the basis of these reports," says Dr Puneet Dewan, head of the WHO's TB programme in South East Asia.

He says more TB drugs are sold in India than the number of patients. "This could mean that a lot of people are being treated who are not diseased."

In a rare "negative policy recommendation", the World Health Organisation recently warned against the "rampant commercial use" of Elisa to test for TB.

Dr Sen says he regularly turns back patients asking for Elisa, but thousands of labs across Bihar continue to carry out these tests.

Experts, however, say the problem will continue unless new technologies are developed for a rapid and accurate diagnosis of TB cases.

Dr Dewan says the WHO has recently approved for field trials a machine called GeneXpert which studies DNA amplification to test TB.

Although GeneXpert sill has a long way to travel, doctors say it has the potential to change the face of TB diagnostics.

"It would not require specially trained staff to operate it, it would not need any special infrastructure to run it. You don't need a three-room lab for GeneXpert, you just need a table," Dr Sen says.

In test conditions it has been able to detect even multi drug-resistant cases in under two hours.

If it works as well in the field, then Bihar's - and India's - TB problem may just be over.