The woman taking on India's communists

- Published

Mamata Banerjee is a street-fighting politician

For a moment, Mamata Banerjee, caught in a crush of people, looks harried, her eyes darting from side to side.

Her safari-suited security men are trying to keep a sea of raucous supporters - men and women, young and old - at bay, and some burly party workers are trying to clear the road of the teeming, unruly hordes ahead.

All traffic has come to a halt as Ms Banerjee's campaign walkathon swings through the rustbelt suburb of Howrah in India's eastern state of West Bengal.

Thousands of people have clogged the roads, and gathered on verandahs and rooftops to catch a glimpse of the diminutive woman who is leading the charge in state polls which begin this month.

Many believe she will almost single-handedly unseat the ruling communist government, which has ruled the state uninterruptedly for 34 years.

Frugal

Ms Banerjee, who has invoked the slogan of rooting for ma-mati-manush (Mother-Earth-People) in her speeches, and lives frugally, is wearing an off-white cotton sari with an apron emblazoned with the party symbol - two tricolour flowers on a bed of grass - and walking in rubber sandals.

"Where is she? Where is she?" scream her supporters, baking in the sun uncomplainingly for hours.

Ms Banerjee has tapped into public disenchantment with the Communists

Suddenly the walkathon is upon them.

People surge ahead, a frisson of excitement runs through the crowd, the slogan shouting reaches a crescendo and a couple of party workers escorting me are swept away in the wave.

"She is here! She is here!" roars the crowd - men and women, some togged out in colourful party tee-shirts, caps and saris and some holding party umbrellas.

Now Ms Banerjee regains her composure. She breaks into a broad smile, clasping her hands into a namaste, the traditional Indian greeting, and waves to people, some of whom throw flowers at her - her minders say later that she is allergic to flowers.

And suddenly she is gone, lost in the multitudes on a gruelling 7km (4.5-mile) walk which takes two hours to finish in the heat and dust and milling crowds and the narrow streets of Howrah, aflame with the flags and bunting of her party and her rivals.

"A new morning beckons. The age of darkness is ending. Change is in the air," says Ms Banerjee at a meeting later.

She uses folksy rhetoric and relentlessly lampoons the communists, using native limerick and doggerel.

She calls her rivals "buccaneers, thieves, and Goebbelsian liars", and derides the film-loving communist chief minister Buddhadeb Bhattacharya for being more comfortable with watching "Truffaut and Godard" rather than the jatra (folk opera) of Bengal.

'Naive'

The provocation: Mr Bhattacharya had told a meeting the previous day that Ms Banerjee's pet evocation of ma-mati-manush sounded "naive and more like the name of a jatra".

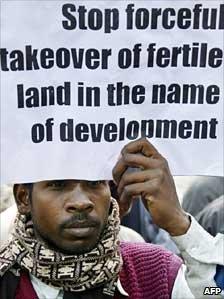

There have been protests against forcible land acquisition in Bengal

"The communist-alliance is on the ventilator. It will be cremated on 13 May [the day the votes are counted]," Ms Banerjee continues.

Here in Bengal, her supporters appear to forget that she is India's railway minister - they call the spitfire 56-year-old didi (elder sister). She has steered her once rag-tag Trinamool Congress party to a position where it looks set to defeat the communist-led alliance.

The commentariat in Bengal also feel that her time may have finally arrived - a clutch of opinion polls suggest that her party - in alliance with Congress, which rules nationally but is junior in West Bengal - is poised to pick up 180-200 seats in the 294-seat assembly.

Even her critics concede that Ms Banerjee, nearly written off after the 2004 general elections when her party won just one of the 42 seats, has bounced back, riding public anger against the communists.

Peasants have accused the communists of trying to acquire fertile farmlands to build factories. The middle classes blame them for not doing enough to prevent the industrial decline of Bengal.

Also, they point out, unlike most politicians who quit the Congress - Ms Banerjee left the party in 1998 to form her breakaway group - she did not return to the party sheepishly after the independent venture failed. Instead, the Trinamool Congress leader has stuck to her guns and become the main opposition in Bengal.

She is also a tough bargainer and has refused to kow-tow to her alliance partners - once the Hindu nationalist BJP, now the left-of-centre Congress party - and has resisted pressure to concede more in seat-sharing arrangements during elections.

Ms Banerjee has also refused to budge from her stand that fertile farmland was being given to India's Tata group to build a factory to make the Nano, the world's cheapest car. The group eventually left Bengal to set up the Nano factory in the western state of Gujarat.

'Rebel'

"She has been consistent in her anti-Left stance, she has been a tough negotiator in her alliances and is a street-fighter. She's an archetypal rebel," says analyst and former BBC correspondent Subir Bhaumik.

Her communist rivals dismiss Ms Banerjee, saying she is all "sound and fury" and is an untested administrator, despite her ongoing stint as federal railway minister.

Ms Banerjee has set out an ambitious first 200-day "action agenda" for "industrial revival and employment generation" in her exhaustive 55-page manifesto. She aims to develop "world class centres of [industrial] excellence, revive the moribund jute industry, promote Bengal as a tourist destination and revamp the ailing health sector, among other things.

Ms Banerjee's party controls the municipality in Calcutta

She even wants to introduce river cruises on the Ganges skirting Calcutta - "in line with Thames in London, Nile in Cairo, Seine in Paris and Hudson in New York" - and revamp a well-known park outside the city along the lines of "Kew Gardens, London".

"She has been very tall on promises. Her real challenge will be delivering on them. She has to walk her talk. It will be interesting to see how she copes with the challenges," says Mr Bhaumik.

For the moment, Ms Banerjee has shed her shrill and sometimes crude rhetoric and her street-fighting ways to appear as a more reasonable and responsible politician.

"All communists are not bad," she says, on her campaign. "Opportunist communists are bad."

In a country where women politicians are often caricatured more than their male counterparts, the indefatigable Ms Banerjee is one of the few mass leaders left.

There is enough evidence of that in a public meeting in north Bengal where thousands have waited for hours to listen to her speak.

"Will you vote for us?" Ms Banerjee asks the dimly-lit meeting.

"Yes, yes," a chorus rises from the audience.

"So go out and bell the cat [defeat the communists]," she exhorts, waving quickly to the crowds. Then she disappears into the inky night.