India female foeticide: Can Bihar save its girls?

- Published

Baby Anushka was almost not born

The latest census figures have come as a big jolt to the authorities in the northern Indian state of Bihar who are just waking up to the dangers of female foeticide. So what are they doing about it? The BBC's Geeta Pandey reports from Patna.

On a steaming hot day, nearly two dozen women have gathered in the office of the government-run child development project in the Bihar village of Vidupur.

Most are accompanied by their little daughters. All of them have a white sheet of paper which they scramble to show me.

It's a precious document - it carries the name of the girl, her date of birth and other details. And it's proof that she is enrolled for the government's Kanya Suraksha Yojana (Girl Protection Scheme).

Under the scheme, the state invests 2,000 rupees ($44; $27) in a fund in the name of the girl. The money grows along with the child - once she reaches 18, officials say it will be worth about 10 times that amount, and could be used to pay for her wedding or to fund a college education.

The scheme is available only to those living below the poverty line and a family can enrol just two daughters.

The initiative, announced in November 2007, is part of the government's plan to make baby girls wanted and, at the same time, make small families an attractive idea.

"The scheme was launched to ensure the girl child is allowed to be born, that her birth is celebrated, and that she is cared for," says Irina Sinha, an official in the state government's Women's Development Corporation.

A miracle

A mere mile from Vidupur is another villager, Bihvarpur, where a social worker takes me to see baby Anuskha.

The youngest of four siblings - all girls - Anuskha is nine months old. The very fact that she exists in flesh and blood is a miracle.

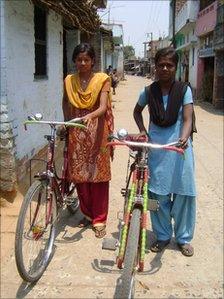

Puja Kumari and Kiran Thakur were given free bicycles by the government

In 2009, when her mother, Sunita Devi, became pregnant, she went to a clinic in the nearby town of Hajipur for an ultrasound test.

"I asked the doctor whether it was a girl or a boy. I told her, 'I'm a poor person. I already have three daughters. I can't look after another girl'," she tells me.

The doctor told her it was a girl. "I asked for an abortion. She said it would cost 5,000 rupees [$110; £68]."

Sunita did not have the money so a few months later, baby Anushka was born. Since the illiterate mother does not have a birth certificate for her, Anushka cannot claim any state benefit.

"Now where will I find the money to feed and clothe them? And how will I pay for their dowries?" Sunita asks.

In mostly rural, feudal, male-dominated Bihar, women have very low status. Everyone I spoke to talked about the evil of the dowry system. Rich or poor, no-one's exempt from this menace.

And that, almost everyone agrees, is the main reason why girls are not welcome.

'Good policies'

"People here feel very sorry when a girl child is born," says Rafay Eajaz Hussain of the Public Health Resource Network, an NGO in the state capital, Patna.

To change that, he says, the government has announced "some good policies for the girl child".

Sunita Devi has four daughters

"They are given books and uniform allowances and when a girl reaches the 9th grade, she gets a free bicycle."

Just a little over a mile from Vidupur and Bihvarpur is the village of Navanagar. Here, teenagers Puja Kumari and Kiran Thakur pose for photos with the gleaming new bicycles they have received from the government.

The three villages are in Vaishali district, a 45-minute drive from Patna, across the River Ganges.

According to preliminary data released by the 2011 census, Vaishali has the worst child sex ratio in the state, with 894 girls for every 1,000 boys aged 0-6. Patna is second from bottom with 899.

At 933, the state's child sex ratio is still better than the national average of 914, but it's dropped a long way from the than 981 which the state registered 30 years ago.

This has sent the alarm bells ringing in the administration.

Bihar is one of India's poorest states with 57% of its 103 million population living in extreme poverty. It also scores very low on human development indexes with high levels of female illiteracy and widespread malnutrition.

"The sex ratio has not been high on the government agenda. The census data has given us all a big jolt," Ms Sinha says.

"So far, we were focused on child marriages and malnutrition."

'Problem of affluence'

Mr Hussain says perhaps what has prevented a large-scale bloodbath of baby girls in the state is the endemic poverty and lack of development.

"In rural Bihar, information on sex selection is not easily accessible. Also, the poor cannot afford to pay for the ultrasound or the termination of pregnancy," he says.

Ms Sinha says the problem of female foeticide is seen more in the middle class and affluent families and urban areas which have access to technology.

"In cities what we see is a daughter who is 16 and then a son who is six - so what happened in between?"

Given that the state's girl-friendly schemes are meant for the poorest of the poor, while foeticide is mostly practiced by the affluent, is the government barking up the wrong tree?

"Not really," says Dr OP Kansal of Unicef.

"Bihar has become the donors' darling. In the past five years, the state has launched many development schemes and as people come out of poverty and get more affluent, more girl children will be killed unless something is done now.

"People would want smaller families and our obsession with the male child means they would want sons rather than daughters."

Sign language

India legally allows abortion up to 12 weeks of pregnancy. Gender can be determined only after 14 weeks of pregnancy and sex selective abortion is illegal. But medical practitioners have found a way of circumventing the law.

In Bihar, there are more than 1,000 ultrasound clinics, many of them still unregistered.

"We want to register them all. And we will punish those who carry out illegal sex determination," Bihar Health Minister Ashwini Chaubey says.

The Bihar government has introduced several schemes to promote the girl child

An ultrasound scan costs a few hundred rupees and there is zero paperwork to avoid leaving any proof.

The parents are never given anything in writing. Often, the gender of the foetus is conveyed by signs - a pat on the side of the nose signifies the nose-ring (or a girl) while a twirl of the moustache is meant to be a boy.

Mr Chaubey says the problem has to be dealt with in two steps.

In the short term, he says his government is committed to strictly enforcing the law against ultrasound clinics - they will be raided and sealed.

In the long run, everyone will have to work together to change the mindsets of people.

"We are going to tell people that female foeticide is wrong. It's a crime - religious and social. And our girl-friendly schemes will help change minds," he says.

Mr Hussain, however, is not convinced. "Populist schemes will help politicians win elections, but they will not save the girl child," he says.

"Small steps will not help. We need a revolution. And I'm not seeing that coming through."

He is right. Despite all the girl-friendly schemes, little Anushka almost didn't get born.