Gruesome history of India's 'house of horrors'

- Published

Overgrown bougainvillea now hides India's "house of horrors" in a wealthy Delhi suburb

Delhi's "house of horrors", as the Indian media call it, is now hidden behind an overgrown bougainvillea covered in pretty flowers.

But house D5 will forever be remembered as the place where at least 19 young women and children were raped, killed and dismembered.

The two men living there were accused of the dreadful crimes; one of them, Surinder Koli, has since been sentenced to death. He was due to be executed this week, but the date has been put off while India's president considers a mercy plea.

Its gate is blocked by police barriers, and life in the street outside carries on as normal.

There is a man selling water melons, another herding cattle. Signs on the gates of the neighbouring mansions show that lawyers, doctors and other professionals live there.

The deaths were discovered in December 2006 after body parts and children's clothing were found blocking the sewer running in front of the house.

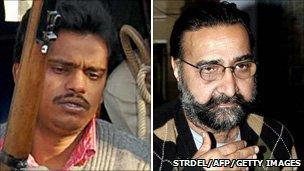

Surinder Koli (L) and Monindher Pandher (R) are accused of murdering 19 young women and children

Koli worked in D5 as a servant for the owner, Monindher Pandher, who was a businessman. In the five cases which have so far gone to trial, Pandher has been let off due to a lack of evidence, but is still in jail facing other charges. He says he is innocent.

The murders caused an outcry because they seemed to exemplify the divisions that still exist in India despite its economic miracle.

The killings took place in a wealthy Delhi suburb but the victims came from families that had migrated from the countryside. The families accused the police of ignoring their pleas for help in tracking down their missing children because they were poor.

They lived in a slum, Nithari, which backed onto the house. The children were allegedly lured to their deaths by Koli, who offered them sweets and chocolate.

He confessed in court to cannibalism and necrophilia.

Selective justice

When the crimes emerged, these details were not known and when I first visited Nithari what struck me most was the community's anger at the authorities.

Four years on, it is still strong.

"We haven't seen justice yet, they should have let us deal with the two men," Seema, a tea seller, said.

One of the first girls to disappear was Rachna, an eight year old. Her father Pappu Lal is the caretaker of a house three doors up from D5. Every day he walks past the scene of his child's murder.

"Yes today we're still angry. Whenever I think about my child I feel so sorry, I feel like crying. And whenever I see D5 I feel like burning it down," he said.

"Justice hasn't yet been done and the truth still hasn't come out."

Pappu Lal shares the widely held view in Nithari that the police and courts are covering up a conspiracy.

"We don't believe that one man can have done it all by himself. Evidence has been destroyed. But we are poor. How can we influence the courts?"

When the children started disappearing, the families asked a local social activist, Ushaa Thakur, to help them with the police.

But she says they were just not interested.

"The police said the girls had just run off with some boy, or gone to some village. They asked me why I was bothering with such matters."

After the first corpses were discovered the residents became so furious that they attacked the police. A senior officer denied to me at the time that they had ignored the complaints, but later six policemen were suspended.

According to Ushaa Thakur, the case reflects extremely badly on her country.

"India is in a very miserable state. People are just not bothered, and even if they are, they don't want to waste time on such things, on poor people, on the people who are crying," she said.

Failing the poor

But at least the killings forced politicians and the police to promise to do more about the scandal of India's missing children.

A recent report found that about 60,000 disappear across the country every year. In the capital the number is five a day. Most are forced into illegal work.

According to Kailash Satyarthi of Global March, a child rights NGO, nothing has yet improved.

"As we all know, the mass memory, the public memory, is very short. For a few months after Nithari there was a lot of hue and cry but then it slowed down," he told me.

"We have warned the government that children might be taken away and their organs could be sold or they could be killed, and that this could happen with many, many children."

The Nithari killings were especially gruesome but they highlighted issues that are all too common in India - the inequality, the failings of the police and the sad fate of so many its children.