Baba Ramdev fast: Just cause or blackmail?

- Published

- comments

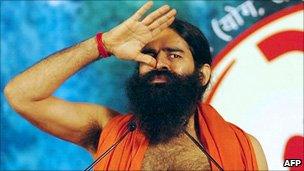

Baba Ramdev is a popular yoga guru

In this open season of hunger strikes, India is bracing for another one, beginning this weekend.

After activist Anna Hazare , external with his 96-hour fast in April demanding tough anti-corruption laws, the government is now debating a contentious law for a corruption ombudsman with Mr Hazare's "civil society" representatives. Now popular yoga guru Baba Ramdev has decided to begin a "fast unto death" demanding a crackdown on illicit money.

The north Indian saffron-clad yoga teacher presides over a thriving yoga and health empire, including an island in Scotland, external. He abhors multinational corporations, believes the World Health Organisation (WHO) is an American big pharma "conspiracy", claims his exercises can cure HIV, is openly homophobic and advocates capital punishment for the corrupt. He also believes yoga can "rescue" India. His critics believe he is uncomfortably close to Hindu nationalist organisations.

So why is he pitching tent, external in Delhi with 60 doctors, an intensive care unit, 1,300 toilets, a huge media centre, seven giant TV screens broadcasting the anti-graft fast and an estimated 20,000 supporters in attendance? Is he a publicity seeker or is he using his popularity to highlight a just cause?

"There are two ways of changing a system," Baba Ramdev said in a recent interview, external. "One to enter politics directly, and [secondly] to create such an enormous groundswell of pressure from the public that the political class is forced to act responsibly."

His supporters say there is a legitimate space for people like him, who have influence over thousands of followers, and who can rally them against corruption, India's biggest existential threat. They say people like him and Anna Hazare actually do democracy proud by bringing citizens' pressure to bear on government.

There have been widespread protests against corruption in India

But many question whether a yoga merchant should become a self-appointed leader of the anti-corruption drive. They believe such fasts in a constitutional democracy can easily become a coercive tool to blackmail government. One of India's greatest thinkers, BR Ambedkar, eloquently wrote that such methods introduced a "grammar of anarchy" to a democracy. Pratap Bhanu Mehta, a respected commentator and head of a leading Indian think-tank, believes that Baba Ramdev's fast is an "absurdity, an absolute travesty of democracy and phenomenally dangerous trend".

An effete government, many say, has allowed things to come to such a pass. A bewildered sociologist friend of mine believes that by abdicating its responsibility in making a serious and sincere effort to crack down on corruption using available laws and institutions, it has allowed a bunch of "oddballs and fetishists, masquerading as the new Gandhis" to take leadership of a media-driven, largely middle-class anti-graft movement.

Pratap Bhanu Mehta echoes a similar sentiment. "The real issue in this is that we don't have a government, part of the reason you have this problem is that there is no leadership," he told a newspaper.

"Can you imagine a government of a large democracy becoming hostage to someone saying 'I am going on a fast'? If we had a strong government and the prime minister took responsibility for government actions, this situation would not have come about."

When a large number of people lose trust in the government to deliver on promises, they turn to anyone who captures their imagination. This is why Anna Hazare and Baba Ramdev have becoming the darlings of India's restless, politician-baiting middle-class, who are fed up with corruption.