Can civil society win India's corruption battle?

- Published

- comments

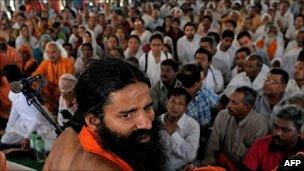

Baba Ramdev's anti-graft strike was broken up by the police

Are sections of India's civil society subverting democracy to pressure the government to push through tough anti-corruption laws?

The beleaguered Congress-party led government appears to think so. The senior-most minister Pranab Mukherjee has fired an uncharacteristic broadside , external at activist Anna Hazare's anti-graft agitation for resorting to hunger strikes, making unreasonable demands like video graphing meetings of a joint panel to discuss an ombudsman law and imposing deadlines on the parliament.

Mr Hazare is a well meaning Gandhian, who has a record of fighting corruption in his home state of Maharashtra. But he also has a predilection for making clumsy statements - he endorses capital punishment for the corrupt, for example. But few Indians deny that Mr Hazare has touched a chord, mostly among the country's fretful, politician-loathing middle classes, by pressuring the government to take a tough stand against corruption. Graft has become a way of Indian life, kept alive by the rulers and ruled alike.

Mr Mukherjee's barb is clearly not aimed at Mr Hazare alone. Last fortnight, Baba Ramdev, a thriving yoga guru with political ambitions, also began a hunger strike in Delhi demanding that the illicit money stashed away in foreign banks by rich Indians be brought back home. After futile negotiations with the guru, the government cracked down on his fast in the middle of the night, baton charged sleeping supporters and evicted him from Delhi. The police action earned the opprobrium of many Indians, and further battered the government's fast-eroding credibility.

Now the government appears to be trying to bottle the genie of Mr Hazare and Baba Ramdev's "movements", both of which it legitimised in the first place through recognition and negotiation. It seems to be also unable to handle the vicissitudes of these agitations, with its leaders blowing hot and cold against the government. Such a civil society movement, Pranab Mukherjee said, amounts to a "sinister move of destroying the fine balance between the three organs of government enshrined in our constitution".

"If someone dictates terms from outside to the government, does it not weaken or subvert democracy? It is a big question... We are all civil society, no one is uncivil."

Clearly, Mr Mukherjee's definition of civil society in the haste of a press conference is literal. The World Bank defines civil society to "refer to a wide array of non-governmental and not-for-profit organisations that have a presence in public life, expressing the interests and values of their members or others, based on ethical, cultural, political, scientific, religious or philanthropic considerations".

The middle-class is backing the anti-corruption movement

So civil society can be community groups, NGOs, labour unions, indigenous groups, charitable organisations, faith-based organisations, professional associations and foundations.

There is no denying that Anna Hazare and Baba Ramdev have the right to galvanise their supporters to take on the scourge of corruption, despite their spotty ideologies and kooky prescriptions for social reforms. At the same time, civil society can become a double-edged source. Political scientists like Neera Chandoke have cautioned against the overuse of civil society. "We should be careful in whose hands civil society ends up - eastern Europeans have exchanged the tyrannies of socialism and party apparatuses for the tyrannies of capitalism, political elites, corporate bureaucracies and ethnic majorities determined to stamp out any kind of plural life," she says. Baba Ramdev's anti-graft protest, for example, was being openly backed by right-wing Hindu nationalist organisations. Many believe that it was taking a disturbingly strident political hue.

The other point which needs to be made is that this "war against corruption" - exaggerated by many as India's second war of independence and similar hyperbole - is being seen by many as the high noon of Indian activism and civil society movement. This, many believe, is an insult to India's many well-known and unknown - and unsung - activists who are working quietly and ushering in changes without whining loudly that India has failed itself. Civil society groups led by stellar activists have saved lakes and trees and fought for the poor and dispossessed. By deifying Anna Hazare and Baba Ramdev, India appears to have forgotten outstanding activists like Medha Patkar, external and Sunderlal Bahuguna, external, who have a long and stirring track record. What about the brave Irom Sharmila Chanu, external, a 40-year-old woman who has spent more than a decade fasting against a draconian anti-insurgent law, external in the north-eastern state of Manipur? (She has been force-fed through a piece in her nose since November 2000)

India has seen deeper, meaningful civil society movements which have been blithely ignored by most of middle class in the past. Only when a protest comes to Delhi in the full glare of 24/7 news television does it get attention. And more so, when it rallies against corruption - which actually hurts the poor more than the rich and the middle class.

By all means, many believe, an enlarged and more representative civil society - ideally a larger, wider group of people from all over the country, not just a bunch of well meaning lawyers and activists from Delhi - should be putting pressure on a stubborn government to act against corruption. Also, as development expert Rajesh Tandon reminds us, civil society is not intrinsically virtuous. And good graft-free governance does not come from reforming the state alone - it demands the reformation of society and its people. There are no short cuts to a more virtuous India.