Why mining in India is a source of corruption

- Published

India cannot afford to stop mining if its economy is to continue growing

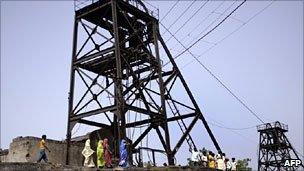

The mining scandal which led to the unseating of a prominent leader in India's southern state of Karnataka is the latest scandal to hit the industry.

BS Yeddyurappa of India's main opposition Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) quit recently after an anti-corruption report named him as a key suspect in a scam which allegedly cost the exchequer more than $3bn (£1.8bn). Mr Yeddyurappa denies any wrongdoing.

But what is undeniable is that illegal mining has been rife for years in Karnataka. The state produces about 45 million tonnes of iron ore a year and exports more than half of it to China.

It is not the only state in India where mining has become a controversial trade.

South Korean company Posco's plan to build a $12bn steel plant - India's largest foreign investment project - in the eastern state of Orissa has run into heavy weather over how much iron ore it should be allowed to export. More recently, acquiring land from the farmers for the plant has also become a problem.

Controversial

And last August India rejected controversial plans by mining group Vedanta to extract bauxite in the Niyamgiri area of Orissa.

The company has proposed a $2.7bn investment in the area, a project which it says will bring jobs and development to one of the country's poorest districts. It has previously said it has complied with all rules and regulations.

Mining has not helped local communities

The local tribespeople say the mining project will destroy their sacred hill and their source of livelihood.

Why has mining become a source of massive corruption in India?

For one, India is rich in lucrative minerals.

It is the world's largest producer and exporter of mica, the third largest producer of coal and the second largest producer of barites.

India is also the world's fourth, fifth and seventh largest producer of iron ore, bauxite and manganese respectively.

Some of the most mineral-rich parts of the country are situated in regions that are home to some of the poorest tribal communities.

These places comprise a third of India's area and are also hotbeds of Maoist insurgency - largely a consequence of sharp inequalities in income and wealth.

Over the last two decades, India has opened up mining to private companies without strong and independent regulation.

A note from the federal ministry of mines talks about the mixed results of this opening up.

It says "legal and regulatory loopholes and inadequate policing has allowed the illegal mining operations to flourish and grow".

So much so an ombudsman report on mining in Karnataka found that the promoters of privately owned mining companies in the Ballery region - where most of the mines are located - paid off politicians, and then joined politics themselves, rising to positions in the state government.

These mining businessmen-turned-politicians exerted so much influence over the local officials that the Indian media began describing Bellary as a "new republic".

Ugly underbelly

Investigations have shown that while the government receives paltry royalties from private mining companies, a few influential oligarchs in collusion with politicians have made massive profits.

India is rich in lucrative minerals

No wonder that for many in India, mining has come to epitomise the ugly underbelly of economic liberalisation - crony capitalism and rampant loot of natural resources.

The mines ministry now admits that "mining activities have resulted in little local benefit and, in fact, has been at the cost of environmental degradation".

Now the government plans to amend a 54-year-old law to make it mandatory for mining companies to put in place rehabilitation and resettlement programmes for the people affected by their activities and protect the environment.

Otherwise, as the government itself concedes, mining will continue to contribute to social dissatisfaction and unrest.

India cannot afford to stop mining if its economy has to grow.

But it needs stronger regulation and a fair deal to the communities that live on lands rich in minerals.

Only then India's "resource curse", as many economists describe the dichotomy of the poorest living on the richest lands, can be turned into a "resource boon".

The writer is an independent journalist and has produced and directed a number of documentary films on mining in India.

- Published21 July 2011

- Published2 August 2011

- Published17 December 2010

- Published24 August 2010