Land bill: A new deal for farmers?

- Published

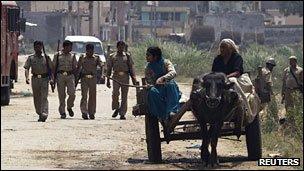

Land acquisition has become a controversial issue

Conflicts over land are deepening India's development fault lines.

In recent years, farmers have clashed with the police while resisting efforts by the government to , externalfor factories and housing, challenged the setting up of vast special economic zones, and even scuppered a car factory, external being built on farmland acquired by the government. Scenting votes, politicians have rushed in to commiserate with irate farmers protesting at the takeover of their land.

So why has land become so contentious? Farm productivity and revenues have been declining for years. Agriculture contributes less than a quarter to India's GDP. But India has the second largest arable area in the world after the US and, more importantly, more than 70% of Indians continue to live off the land. They have primordial and cultural links with land; land gives them dignity and security. All this makes land an explosive issue, both socially and politically.

So when governments and businessmen go hunting for land in rural India to set up factories or develop housing or build a highway, farmers become suspicious.

Lack of trust

Most of them don't trust commercial developers and government intermediaries. Many feel industrialisation will not bring them any benefits: they fear their children may not get jobs or be qualified enough for them in the factories that are built. Since their banking habits are rudimentary, they are not empowered enough to prudently invest money that may come from selling off their land.

The government of India has not been a great help either. Using a 117-year-old colonial law called the Land Acquisition Act, external - aptly called the Indian Expropriation Act in its early days - it has, for decades, forcibly obtained land without the consent of owners to build roads, bridges, factories, highways and homes - all in the name of 'public interest'. The law been tweaked over the years, but it essentially remains an unfair and antiquated one.

Protests against land acquisition forced a car factory in Bengal to shut

That is why the new Land Acquisition and Amendment Bill, external - soon to be tabled in parliament - has become a talking point in India. In many ways, it promises to be a game-changer of sorts. It proposes a fairer deal for land owners by giving them better compensation, expands the rights of those displaced and limits acquisitions to so-called "public purposes".

Two examples of how the radical new law would work: it proposes to pay farmers up to six times more than the market rate for land; and contains a key stipulation requiring the consent of 80% of land owners for their land to be sold for industry.

That's not all. The proposed new law also says social impact studies must be conducted for large scale displacement - 4,000 families in the plains or 200 families in hill and tribal areas - when land is being acquired. Some 40 million people in India have been displaced by land takeovers for developmental projects since 1950. By one estimate, an alarming 75% of them are still awaiting rehabilitation.

The proposed law also talks about compensation for tribal people, forest dwellers and non-land owning farm workers. It prohibits changing the use of land after it is acquired for a specific purpose.

Friction

It is heartening to see that the bill ensures a new deal for the farmers. But the new law could end up creating more friction between agriculture and industry, fear many.

Most agree that India needs a fairer land acquisition law. At the same time few would disagree that the country needs more industries to spur growth and create more jobs - and to set up more industries you need more land.

There have been clashes over land acquisition

Industry utilises a miniscule 3%-4% of all land in India today. If it is to contribute to a quarter of the country's GDP, it would need to occupy 15% of the land, reckon industry lobbyists.

Industry groups are already saying they need government help in acquisition and rehabilitation, clearer definition of public purpose, greater clarity of what constitutes industrialisation where benefits accrue to people.

They believe it will be difficult for business houses to secure the consent of 80% of the affected families, and want the government to be involved in the purchase of land in which 50% or more of the land owners have given consent. They say the government proposal requiring corporates to provide from the rehabilitation and settlement will drive up prices of land sharply. Businesses say it is inappropriate to ban the use of multi-crop land for infrastructure development, like roads and bridges. This will, they say, put about 55 million hectares or 40% of the arable land beyond acquisition.

Economist Pranab Bardhan says the entire process of land transfer, including compensation and resettlement, should be handed over to an independent quasi-judicial authority or a regulatory body to ensure that it is free from political influence.

Would the new law end up more creating more road blocks and bureaucracy so it ends up stifling industry further? Or will it satisfy both business and farmers and strike a happy balance between development and displacement? As India's leading land expert, Debabrata Bandopadhyay, says: "Let it get implemented and see how it works."