The Afghan-Pakistan militant nexus

- Published

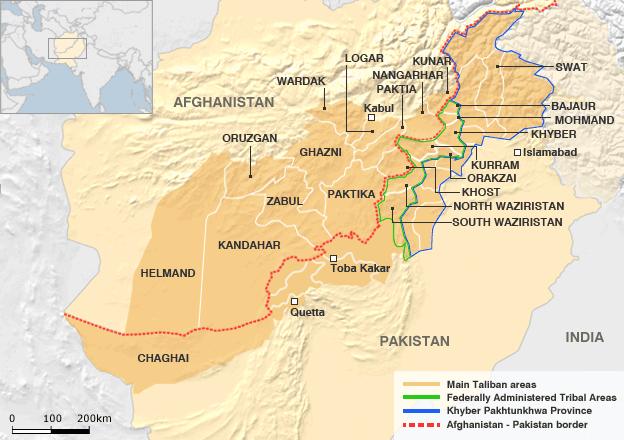

The Afghan-Pakistan border region has become the front line in the war against Islamic militants. The area is a patchwork quilt of territory where militant groups have gained strength in some places but lost ground in others. The BBC's M Ilyas Khan reports.

HELMAND, CHAGHAI

Kabul's writ has never run strong in the remote southern plains of Helmand province which is why it emerged as the most significant Taliban stronghold in Afghanistan immediately after the US-led invasion of 2001. Further south, across the border in Pakistan, lies the equally remote Noshki-Chaghai region of Balochistan province.

Since 9/11 this region has been in turmoil. In the Baramcha area on the Afghan side of the border, the Taliban have until recently maintained a major base, with IED (improvised explosive device) factories, weapons caches and residential camps. From there they have been controlling militant activities as far afield as Nimroz and Farah provinces in the west, Uruzgan in the centre of the country and parts of Kandahar province. They also link up with groups based in the Waziristan region of Pakistan.

In the past, the Taliban from Baramcha region have been moving freely across the border, and often take their injured to hospitals in the Pakistani town of Dalbandin in Chaghai.

The Helmand Taliban have been able to capture territory and hold it, mostly in the south, but also in some northern parts of the province. They have constantly threatened traffic on the highway that connects Kandahar with Herat.

But since US President Barack Obama's 2010 decision to launch a troop surge, Western forces were able to carry out a mostly successful sweeping operation in areas as far south as Baramcha to destroy the militant infrastructure.

In spite of this, the Taliban's freedom to move across the border in Baramcha and nearby areas has not been fully curtailed.

British troops have a major base in the town of Gereshk, along the Kandahar-Herat road. Fresh American troops have also been deployed in the area.

KANDAHAR, QUETTA

Kandahar has the symbolic importance of being the spiritual centre of the Taliban movement and also the place of its origin. The supreme Taliban leader, Mullah Mohammad Omar, made the city his headquarters when the Taliban came to power in 1996. Top al-Qaeda leaders, including Osama Bin Laden, preferred it to the country's political capital, Kabul.

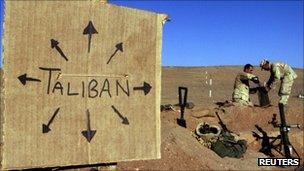

Conflict on the border areas has resulted in heavy casualties on both sides

As such, the control of Kandahar province is a matter of great prestige. The first suicide attacks in Afghanistan took place in Kandahar in 2005-06, and were linked to al-Qaeda. Kandahar has seen some high-profile jail breaks and assassination attempts, including one on President Karzai.

The Afghan government has prevented the Taliban from seizing control of any significant district centre or town. International forces have large bases in the airport area as well as at the former residence of Mullah Omar in the western suburbs of Kandahar city.

Mullah Omar is thought by some to be hiding in Kandahar or Helmand. Others suspect he is in Pakistan.

During 2007-09, the Taliban managed to infiltrate and set up entrenched positions in the heavily-populated agricultural zone of central Kandahar province, from where they exerted pressure on Kandahar city.

They also set up IED factories in this region and conducted a relentless bombing campaign against Western forces, frustrating their attempts to disrupt Taliban activity.

But since the 2010 troop surge, the Taliban have been dislodged from these positions, although they continue to have a strong presence in the countryside, and have carried out a number suicide attacks to assassinate high value targets in and around Kandahar city.

Afghan and Western officials have in the past said the Taliban have used Quetta, the capital of the Pakistani province of Balochistan, as a major hideout as well as other Pakistani towns along the Kandahar border.

Areas on the Pakistan side stretching north-eastwards along the border from Quetta to the town of Zhob are inhabited by Pashtun tribes.

Taliban activity in Balochistan is largely related to operations inside Afghanistan and is of no immediate concern to Islamabad.

The so-called Quetta Shura leadership, alleged by the US to direct much of the Taliban's activity in Afghanistan, is said to be based in the city.

But Pakistani authorities have denied the existence of such a Taliban council in Quetta - or that the Taliban have a major presence in Balochistan.

ZABUL, TOBA KAKAR

Afghanistan's Zabul province lies to the north of Kandahar, along the Toba Kakar mountain range that separates it from the Pakistani districts of Killa Saifullah and Killa Abdullah. The mountains are remote, and have been largely quiet except for a couple of occasions when Pakistani security forces scoured them for al-Qaeda suspects.

Reports from Afghanistan say militants use the area in special circumstances. In early 2002, Taliban militants fleeing US forces in Paktia and Paktika provinces took a detour through South Waziristan to re-enter Afghanistan via Zabul. Occasionally, Taliban insurgents use the Toba Kakar passes when infiltration through South Waziristan is difficult due to intensified vigilance by Pakistani and Afghan border guards.

Zabul provides access to the Afghan provinces of Ghazni, Uruzgan and Kandahar. In fact, it was from here that Taliban first started to infiltrate Kandahar in 2002-03.

There are few Afghan or foreign forces in the area, except on the highway that connects Qalat, the capital of Zabul, to Kandahar in the south-west, and Ghazni and Kabul in the north.

Taliban activity along parts of this highway has forced government officials, aid workers and journalists to give up travelling on this road.

KURRAM, ORAKZAI, KHYBER

As the Pakistani military strategists who organised Afghan guerrillas against the Soviets in the 1980s discovered to their delight, Kurram is the best location along the entire Pakistan-Afghanistan border to put pressure on the Afghan capital, Kabul, which is just 90km (56 miles) away. But because the region is inhabited by a Shia tribe that opposes the Taliban for religious reasons, the Taliban have not been able to get a foothold here.

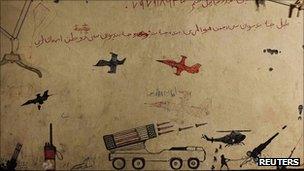

Western forces have been unable to destroy militant infrastructures

The Taliban, with their primary interest in the war in Afghanistan, have also steered clear of Orakzai tribal district because it does not share a border with Afghanistan and is therefore of no strategic value.

But Taliban groups motivated by sectarian strife, or those trying to drive Pakistani forces out of the tribal region, have set up bases both in Lower Kurram, where there are few Shias, and Orakzai.

This area links up with the town of Mir Ali in North Waziristan to the south, and Afridi tribal territory in Darra Adamkhel and Khyber in the north. It was overseen by Hakimullah Mehsud until the death of his top commander, Baitullah Mehsud, in a suspected US missile attack in August 2009. Hakimullah Mehsud has since assumed leadership of the group and has moved to the Waziristan region.

Hakimullah Mehsud was believed to command an armed force of more than 2,000 fighters of varying ability. From their bases in Orakzai and areas north of Mir Ali in North Waziristan, these fighters tried to squeeze the Shias of Upper Kurram valley and those living in the Hangu distinct of Pakistan's Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province.

They also infiltrated the Khyber region and forged ties with mostly criminal groups that have been operating there under the guise of being Taliban fighters. One such group is led by Mangal Bagh. Apart from kidnappings-for-ransom and car-jackings, these groups have also been involved in looting supplies being shipped to international forces in Afghanistan via a road that connects the Pakistani port of Karachi with the country's north-west and passes through the Darra Adamkhel-Khyber region.

These groups have also carried out rocket attacks and bombings inside Peshawar city, the capital of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province. More recently, they are suspected of setting fire to hundreds of trucks carrying Nato supplies at a transit terminal in Peshawar.

Meanwhile, groups based in Orakzai-Khyber region are believed to be behind a spate of bombings in Peshawar and other cities of central Khyber Pakhtunkhwa.

In 2012, hundreds of them raided a jail in the town of Bannu, freeing dozens of Taliban prisoners. In December 2012, a suicide bomber killed Bashir Bilour, a minister in the provincial government and a top leader of the ANP party which governs Khyber Pakhtunkhwa.

PAKTIKA, KHOST, PAKTIA

Taliban sanctuaries in South Waziristan and North Waziristan directly threaten Paktika, Khost and Paktia provinces of Afghanistan. The US-led forces have large bases in the Barmal region of Paktika and in Khost, and several outposts along the border to counter infiltration. Pakistani security forces also man hundreds of border checkposts in the region.

However, infiltration has continued unabated with many hit-and-run attacks on foreign troops.

Tribal identities are particularly strong in Paktika, Khost and Paktia. During the Taliban rule of 1997-2001, these provinces were ruled by their own tribal governors instead of the Kandahari Taliban who held power over the rest of the country.

In the current phase of the fighting they co-ordinate with the militants in Kandahar and Helmand, but they have stuck with their own leadership that dates back to the war against the Soviets in the 1980s.

The veteran Afghan militant Jalaluddin Haqqani, who is a native of Khost, has long been based in North Waziristan. He is an old man now and has stood aside to allow his son, Sirajuddin Haqqani, to lead the anti-US offensive in the region.

Sirajuddin has recently said that his group is no longer based in Waziristan and has moved inside Afghan territory. But many analysts believe their main camps are still located in the sanctuary of the Waziristan region.

SOUTH WAZIRISTAN

South Waziristan, a tribal district in Pakistan's Federally Administered Tribal Areas (Fata), is the first significant sanctuary Islamist militants carved for themselves outside Afghanistan after 9/11.

Militants driven by US troops from the Tora Bora region of Nangarhar province in late 2001, and later from the Shahikot mountains of Paktia in early 2002, poured into the main town, Wana, in their hundreds. They included Arabs, Central Asians, Chechens, Uighur Chinese, Afghans and Pakistanis.

The Taliban in many areas are well armed and highly motivated

Some moved on to urban centres in Punjab and Sindh provinces. Others slipped back into Afghanistan or headed west to Zhob and Quetta and onwards to Iran. But most stayed back and are fighting the Pakistani army.

Unofficial estimates by informed circles put the current number of these foreign fighters at "several hundred". They have concentrations in parts of South and North Waziristan and Bajaur in the Fata region, and have also fanned out to conflict zones in Pakistan's north-western Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Province such as Swat, Dir and Buner.

The eastern half of South Waziristan is inhabited by the Mehsud tribe and the main militant commander here is Hakimullah Mehsud, who rose to this position in August 2009, when a suspected US missile strike led to the killing of the top Mehsud commander, Baitullah Mehsud.

Hakimullah inherited a conglomeration of affiliated militant groups spread across most of north-western Pakistan. But some of these groups have since dispersed or relocated, while others have switched loyalties or simply gone quiet.

The western half of South Waziristan, along the border with Afghanistan, is Ahmedzai Wazir territory where Maulvi Nazir commanded roughly 8,000 to 10,000 militants. Again, most of these cannot be considered battle-hardened and whether they would fight to the last is unclear.

The Mehsuds live only on the Pakistani side, while the Wazirs inhabit both sides of the border. This partly explains the direction the two commanders have taken over the last few years. Maulvi Nazir's men have largely focused on the war in Afghanistan.

They have a peace deal with the Pakistani army and there has been no significant conflict since 2005-06. The army is not known to have intervened to check the infiltration of militants from the Wazir areas into Afghanistan, which is frequently reported.

The Mehsuds on the other hand have focused on Pakistan, which they consider to be serving the interests of "infidel" powers. In 2006, Baitullah Mehsud set up Tehrik Taliban Pakistan (TTP), an umbrella organisation for anti-Pakistan groups operating in Kurram, Orakzai, Khyber, Mohmand, Bajaur, Swat and Dir regions.

The TTP trained their guns on the Pakistani state after the 2007 siege of the Red Mosque in Islamabad, a decision they have yet to reverse.

The Pakistani army started an operation against the TTP's main base in South Waziristan in October 2009, sparking an exodus of tens of thousands of people from the Mehsud tribal region. The bulk of those refugees are yet to return to their homes.

The TTP leadership itself had to relocate to neighbouring North Waziristan. Although occasional skirmishes continue to be reported, the army mostly controls the main towns in the area.

NORTH WAZIRISTAN

North Waziristan is dominated by the Wazir tribe that also inhabits the adjoining Afghan provinces of Paktika and Khost.

North and South Waziristan form the most lethal zone from where militants have been successfully destabilising not only those provinces but others such as Paktia, Ghazni, Wardak and Logar. Groups based in the Waziristan region are known to have carried out attacks in the Afghan capital, Kabul, as well.

The border areas have been bitterly fought over

Current estimates put the number of armed militants in North Waziristan at more than 10,000. A much smaller number are battle hardened.

They are led by Hafiz Gul Bahadur, a veteran of the 1992-96 Afghan civil war who later joined the Taliban. Like Maulvi Nazir in South Waziristan, he has largely focused on the fighting in Afghanistan and has had little friction with Pakistani forces since a 2006 peace deal.

In fact, Taliban loyal to him have confronted foreign fighters based in the eastern North Waziristan town of Mir Ali, who have been attacking Pakistani troops in the region. But like Maulvi Nazir he, too, is perturbed over drone attacks in the region and considers Pakistan responsible for them.

North Waziristan is also the home base of another veteran Afghan militant, Jalaluddin Haqqani. His main priority has been to organise Taliban resistance to Western forces in Afghanistan, but he has also wielded considerable influence over the top commanders in South and North Waziristan.

He is also reported to have maintained links with sections of the Pakistani security establishment and is known to have mediated peace deals between the Pakistani government and the Wazir and Mehsud commanders in the region. Mr Haqqani is now an old man, and his son Sirajuddin has taken over most of his work.

NANGARHAR

The Afghan government has a comparatively firmer grip on the situation in Nangarhar. This is partly due to the compulsion to keep the supply route for Western forces - which connects the Pakistani city of Peshawar with Kabul and passes through Nangarhar - safe.

But there are pockets of resistance in the area. The main Taliban commander here is Anwarul Haq Mujahid, son of a former mujahideen commander, Mohammad Younus Khalis.

This group was responsible for offering protection to Osama Bin Laden in the Tora Bora caves soon after 9/11. In recent months militants from the region have been linking up with the so-called Haqqani network in the Paktika-Khost-Paktia region.

Anwarul Haq Mujahid is also known to have been participating in the Taliban's talks with the Karzai government in Dubai and elsewhere, and is known to have been flying in and out of the country via Pakistan.

BAJAUR, MOHMAND, KUNAR

Analysts had long suspected Pakistan's Bajaur tribal region to be the hiding place of Osama Bin Laden, Ayman al-Zawahiri and other top al-Qaeda leaders.

As such, it is where suspected US drones launched their earliest missile strikes. One drone strike in January 2006 was said to have narrowly missed Ayman al-Zawahiri, although it killed at least 17 others. Another strike nine months later killed 80 people at a religious seminary which US and Pakistani officials said was being used to train militants.

The dominant militant group in Bajaur, and those in the neighbouring Mohmand tribal region, became members of the Baitullah Mehsud-led Tehrik Taliban Pakistan (TTP), which was formed soon afterwards.

Militants in both areas have since fought Pakistani forces inside their respective tribal zones, and have also carried out attacks in the cities of Peshawar, Charsadda and Mardan.

They also conducted the first attacks against security forces in the Malakand region, where the Pakistani forces had to fight against a full-fledged insurgency in and around the Swat valley in the summer of 2009.

Maulvi Faqir Mohammad is the chief commander of the Taliban in Bajaur. He was said to lead a force of nearly 10,000 armed militants but there are indications the ranks have thinned in the wake of the operation in the TTP's home base of South Waziristan.

A year-long military operation against the militants in Bajaur ended early in 2009, followed by a peace agreement under which the dominant tribe in Bajaur, the Mamunds, agreed to surrender the entire TTP leadership to the government.

But that has not happened. The Taliban are back in control in most areas outside the regional capital, Khaar, and Maulvi Faqir Mohammad continues to broadcast his sermons from an FM radio station, although infighting among regional Taliban leaders has considerably reduced his influence.

Bajaur shares a border with the Afghan province of Kunar. Pakistani forces battling the Taliban in Bajaur have complained that US and Afghan troops on the other side of the border have not been doing enough to crack down on the Taliban there.

In Mohmand, about 5,000 militants led by Omar Khalid have been resisting attempts by the security forces to clear them from southern and south-eastern parts of the district in order to reduce pressure on Peshawar and Charsadda.

In recent weeks, their activities have become infrequent and their grip on most of their erstwhile strongholds has loosened.

URUZGAN, GHAZNI, WARDAK, LOGAR

Initially the Taliban were unable to maintain sustained pressure on the country's south-central highlands.

But with sanctuaries in the border region - from the Baramcha area of Helmand province in the south, to some parts of Pakistani Balochistan, Waziristan and Bajaur and Mohmand to the east - the Taliban now have the capacity to render roads in this region unsafe.

Militants have gained and lost territory in Afghanistan and Pakistan

Training camps run by al-Qaeda and Taliban groups have multiplied over the past few years.

The sanctuaries have also afforded the militants endless opportunities to find new recruits.

The Waziristan region is known to be a haven for young suicide bombers trained in remote camps. The Taliban also appear to have had access to sophisticated military equipment and professionally drawn-up battle plans.

The strategy appears to be the same as in the 1980s - "death by a thousand cuts". Sporadic attacks on the security forces and the police have grown more frequent over the years, and have also crept closer to Kabul.

At the same time, the Taliban have destroyed most of the education infrastructure in the countryside, a vital link between the central government and the isolated agrarian population.

Uruzgan has mostly come under pressure from groups in Kandahar and Helmand. These groups, as well as those based in the Waziristan-Paktika-Khost region, have also moved up the highway via Ghazni to infiltrate Wardak to the west and Logar to the east.

Safe and quiet until less than three years ago, both these provinces are now said to be increasingly infiltrated by Taliban fighters.

But they still do not have the capacity to confront troops in open battle, or capture and keep towns.

SWAT

Swat, a former princely state in northern Pakistan, was governed by a British-era law which a court declared unconstitutional in the early 1990s. That triggered a violent campaign for Islamic law to be introduced in Swat and other areas of the Malakand region of which it is part.

The Swat insurgency was effectively put down in 1994 but it re-emerged after 9/11, attracting many battle-hardened militants from Waziristan, Bajaur and the neighbouring district of Dir.

The campaign of the Swat militants has been the most destructive anywhere in Pakistan. They have targeted security forces, police, secular politicians and government-run schools.

By early April 2009, Sharia law had been imposed as part of a deal between the authorities and the local Taliban. However, the militants failed to disarm completely in line with the accord and their fighters spread to neighbouring districts, prompting international concern.

In late April 2009, Pakistani forces had launched an operation in four districts of Malakand region, causing some three million people to flee the fighting. Peace has returned to most of the area, which has since been brought under government control. Most of the refugees have also returned to their homes.

But the leaders of Swat militants and the bulk of hardened fighters were able to slip into Afghanistan's Kunar and Nooristan region via neighbouring Dir district.

Over the last couple of years, these fighters have carved out sanctuaries in areas vacated by American troops in Kunar and Nuristan provinces of Afghanistan, and have from there been launching raids into the border areas of Dir.

This is the first instance in which there has been a reverse flow of militants into Pakistan.

There have also been sporadic attacks inside Swat. In an attack that shocked Pakistanis in October 2012, Taliban gunmen shot and injured three schoolgirls, including prominent education activist Malala Yousafzai.