Narendra Modi: Loved and loathed in his Indian homeland

- Published

It is believed that Mr Modi is intent on winning India's top job

Narendra Modi, one of India's most controversial politicians, has completed 10 years as the chief minister of the western Indian state of Gujarat. All the indications are that he wants a bigger role in politics - that of India's prime minister. But as the BBC's Zubair Ahmed reports from Ahmedabad, there is one significant obstacle to any Modi candidature for the top job - his alleged inaction in the 2002 riots in Gujarat in which 1,000 people, mostly Muslims, died.

It is not difficult to see why Narendra Modi is eager that his image receives something of a makeover.

His reputation has in some sections of Indian society forever been tainted by the communal riots of February 2002, which began after 58 Hindus were allegedly killed by a group of Muslims in the town of Godhra.

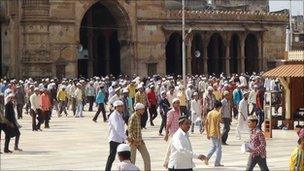

Ahmedabad's Muslim community remains deeply suspicious of Mr Modi

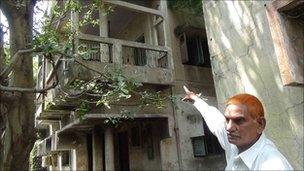

Evidence of that mistrust can clearly be seen at the Gulbarg Housing Society in Ahmedabad, where 68 Muslims were killed during the rioting.

Once, the colony was the pride of the Muslims of Ahmedabad. Its residents were affluent, educated and respected.

Today it is in ruins and no-one lives here. The residents have moved elsewhere in the city and are afraid to return.

On either side of the overgrown grass and bushy patches of land stand the remains of burnt-out two- and three-storeyed buildings.

Windows have been blown away, doors unhinged and the walls still bear the marks of torching.

It is still possible to see what is left of the home of former MP Ehsaan Jaafery, who was killed by the mob on that fateful day along with other residents who had taken refuge in his house.

'We want justice'

Some survived to tell the tale. Sayeed Pathan, aged 55, was one of them.

"A huge mob, armed with swords and bottles filled with soda, descended upon the Gulbarg Housing Society," he said.

"We took shelter in Mr Jaaffery's house as he was the most prominent man here and we thought we would be safe. We fought back and held them at bay until noon.

"But by then we were exhausted and choked in smoke after our homes were torched. We were heavily outnumbered."

By the time the police arrived the mob had killed 68 people.

"I lost 10 members of my family alone," Mr Pathan said.

Sayeed Pathan outside his abandoned home in Ahmedabad's Gulbarg Housing Society

"Mr Jaafery called the chief minister to ask for help, but it never came.

"We will never forget what happened to us that day. We will never forgive Mr Modi... Our wounds are still raw. Nearly 10 years on and we haven't got justice.

"We want justice, we want the culprits to be punished by law. Only then can we move on."

Mr Pathan does not think that Mr Modi's attempt at an image makeover will help him in his quest to become prime minister.

"It's just a facade. He wants to change his image by claiming to be friends with Muslims. But in my view his effort lacks all conviction and sincerity."

Remarkably, Saahil Shaikh, aged 17, survived the massacre.

"I was hiding here," he says while pointing to a corner in a room in Mr Jaaffery's house.

"I was just eight then. I remember hiding behind my mother and two older sisters. First they dragged my mother out and killed her. Then one of my sisters.

"I don't know when they killed my other sister. I ran out, was caught by the mob and was slapped. I fell down on the ground, no-one noticed me, so I slipped out and ran to the police station. Later I learnt they had killed my other sister too."

Saahil's memory of the killings, unlike Mr Pathan's, is fading. He wants to move on.

"Revenge was never on my mind. I am not a political person. I want to join my father's business after my studies and that's all I think about."

'Apology'

On Friday afternoon, inside the 600-year-old mosque in the heart of Ahmedabad, many people are none too complimentary about Mr Modi.

"He doesn't deserve to be the country's prime minister," one man said in views that seemed to be shared by many others.

The chief minister is adored by many Hindus, who say he has brought wealth to Gujarat

Like many other Indian cities, Ahmedabad is named after the city's Muslim founder Sultan Ahmed Shah.

It is fast becoming a modern city with malls, restaurants and cafes.

Outside a burger bar, I asked a group of young boys about Mr Modi's recent three-day fast to promote peace and reconciliation between Hindus and Muslims.

A young boy, a youth member of Mr Modi's Bharatiya Janata Party, swears by him. "He has been the best chief minister of Gujarat. The state has become prosperous during his reign.

"The Congress party paints him as anti-Muslim. But many Muslims have joined him."

Also in the group was a young Muslim boy who seemed completely at ease among his Hindu friends. But when it came to Mr Modi, he was as candid in his opinion as other Muslims in the city.

"We seek a simple apology from him if he is to be forgiven by [our] community," he says.

Electoral maths

In sharp contrast to the the affluent shopping malls and restaurants, the bazaars of Ahmedabad are hundreds of years old.

Its shops and stores seem to be run by Muslim and Hindu stall holders in an equal number. They work cheek by jowl.

"The riots cannot happen here because our numbers are nearly equal," one stallholder said. "They only tend to happen where one community is weaker than the other."

But here too opinion on Mr Modi seems to run largely along communal lines. Muslims in general dislike him, while he seems to be a hero among Hindus.

Muslims comprise nearly 10% of the state. Electorally they cannot prevent Mr Modi from winning the 2013 state assembly elections for yet another term.

But Mr Modi knows that it is not so much his popularity among Muslim voters in Gujarat that he needs to tackle, it is his image across India of being anti-Muslim.

Only then - as one Hindu shopkeeper points out - can he stand a chance of one day becoming prime minister.

- Published19 September 2011

- Published22 April 2011

- Published4 February 2011