Viewpoint: Pakistan seeks Afghan talks between government, Taliban and US

- Published

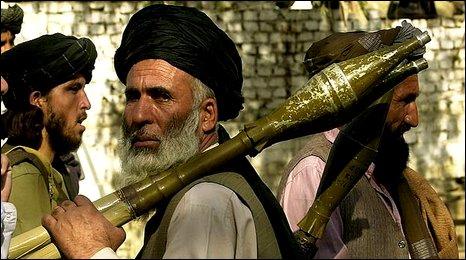

Pakistan has its own internal security headaches

Pakistan's military has undergone a dramatic shift in policy in recent weeks, writes journalist and author Ahmed Rashid. After a decade spent allowing the Afghan Taliban sanctuary and freedom to sustain its insurgency in Afghanistan, it is now pushing for peace talks between the Taliban, the Afghan government and the Americans before Nato forces withdraw from Afghanistan in 2014.

Pakistan's change of heart - if sustained - could open up several new tracks in the peace process, bring about a ceasefire with the Taliban, encourage a wider regional settlement and improve Islamabad's own fraught relations with Washington. Most significantly, a ceasefire and peace talks with the Taliban could dramatically improve the chances of survival for the weak Afghan government and army once Western forces leave.

In a rare sign of the new relationship, recently not one but several senior Afghan officials in private conversations have praised the Pakistan army and its chief, Gen Ashfaq Kayani, for taking visible actions to encourage reconciliation between the Taliban and the Afghan government. For years President Hamid Karzai and other officials have openly accused the army and its Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) of supporting the Afghan Taliban.

"We believe now there is a change in Pakistan's policy and Gen Kiyani is absolutely genuine about helping bring peace to Afghanistan," said a senior Afghan adviser to President Karzai.

In mid-November, Pakistan freed nine Taliban officials it had been holding, releasing them to the Afghan High Peace Council, which is tasked with opening talks with the Taliban. Pakistan said on 3 December it would soon free more Taliban prisoners. Officials said the ISI was holding at least 100 Taliban leaders and foot soldiers but was expected to free them all.

Those Taliban being freed will have complete freedom of movement and association, say senior Pakistan military officials. Pakistan has also pledged not to interfere if the Taliban and the Afghan council want a third country as a venue for future talks. If these initial steps bear fruit, an even more decisive step may come later when the ISI asks hundreds of Taliban commanders and officials fighting Western and Afghan forces inside Afghanistan to support reconciliation talks with Kabul.

Deal next year?

According to senior Afghan, Pakistani and Western officials, Kabul and Islamabad have prepared roadmaps with timelines outlining how future reconciliation talks could take place. While the Afghans have shared their road map with the Pakistanis and the Americans, the Pakistanis will only do so when the Obama administration offers its own plan.

Gen Kayani is now urging Afghan officials to strike a deal with the Taliban as early as next year rather than wait for 2014 as stipulated in its roadmap.

However, the wounding of the Afghan intelligence chief on Thursday by a Taliban suicide bomber will be a setback to the process as it could trigger retribution killings.

Meanwhile, a formerly slow moving tripartite commission made up of the US, Pakistan and Afghanistan has suddenly got teeth as it discusses issues such as safe passage for the Taliban, who will need to travel for talks, and how to take Taliban names off a UN Security Council list which labels them as terrorists.

US-Pakistan relations were broken for the past two years, largely over Afghanistan, but relations are now on the mend. Gen Kayani has recently met US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton and Mr Karzai. However, US officials are more sceptical about the military's intentions and will wait to see what else the military delivers.

How much control Pakistan has over the Taliban is open to question

Meanwhile, the US government has reached internal agreement on a policy document that for the first time links reconciliation with the US military withdrawal in 2014. In 2011 the US began secret talks with the Taliban in Qatar, but the Taliban pulled out in March, accusing the Americans of continuously changing their positions.

At the time the US military and the CIA were opposed to peace talks. The new US policy document signals that there is now much greater consensus in Washington for talks with the Taliban.

So far the Pakistan military has been loath to call its moves a "change" or "shift" of policy, because that would imply that it supported the Taliban in the past. Military officials argue that Pakistan has been calling for Afghan reconciliation for years, but the facts are that in the past the military has not taken any positive steps to implement reconciliation - something it is now doing. The civilian government has little input in Pakistan's Afghanistan policy.

Reluctance

The motives for the army's change of thinking is largely due to the worsening security and economic crises as hundreds of people are killed every month. Pakistan faces an insurgency in the north with terrorist strikes being carried out by the Pakistani Taliban, a separatist movement in Balochistan province and ever increasing ethnic and sectarian violence in Karachi.

The army, which has endured heavy casualties fighting the Pakistani Taliban, is deeply reluctant to get involved in more fighting. Gen Kayani is now banking on the hope that reconciliation among the Afghans will have a knock-on positive effect on the Pakistani Taliban also - depriving them of legitimacy and recruits.

There are several balls now in play. The US insists that the Qatar process is not dead and will respond positively if the Taliban resume that dialogue. Pakistan is not part of the Qatar process and is anxious that its own peace process gets off the ground. Until now the Taliban have said they will not talk to the Kabul government, but Pakistan may get them to change their mind. Qatar's failure has also led to a fierce intra-Taliban debate about the usefulness of talks.

Pakistan does not control the Taliban and nor can it force them to the table. However a signal from the military at the right time that Taliban safe havens, recruitment drives, fundraising and other activities will come to an end by a certain date will put enormous pressure on the Taliban. Yet Pakistan cannot afford to antagonise the Taliban so that another front is opened and they join up with Pakistani extremists to fight the government.

Time is now of the essence, even for the Taliban as their own public support base would not relish the thought of war continuing beyond 2014. And although President Karzai is unpopular, he cannot be a candidate for presidential elections in 2014, which now offers the opportunity of a new and invigorated Afghan leadership.

Pakistan has supported the Taliban for too long and has paid a bitter, bloody price. However if all players are now learning that there is no way forward except for reconciliation, that effort needs uninhibited international support.

The Americans in particular need to appoint a heavyweight diplomat to take the peace process forward, and President Obama needs to personally get engaged - something he has declined to do so far.

Nato needs to play less of a waiting game and be more proactive in pushing the US to speed up the talks process. Above all, the Afghans who have battled for 34 years need to show maturity and seek a peaceful resolution to their wars.