The mammoth military task of leaving Afghanistan

- Published

As the UK and the US prepare to withdraw the last remaining troops from Afghanistan, hundreds of bases, thousands of vehicles and tonnes of equipment are being packed up and shipped home, sold off or scrapped. Just how is this done? Dominic Bailey finds out.

Withdrawing international forces from Afghanistan by the end of December 2014 is not just a case of putting troops on aircraft and flying them home.

The mammoth logistical operation to withdraw by land, sea and air is well under way and ongoing, as combat missions continue until the 31 December deadline.

Nato estimates that about 218,000 vehicles and containers of military equipment need to be shipped out of Afghanistan between March 2012 and December 2014. To date, approximately 80,000 vehicles and containers have been moved out of theatre.

What the UK is bringing back

£300m

Cost of UK withdrawal

-

5,500 containers of equipment

-

3,345 vehicles/major equipment

-

50 aircraft

-

400 tonnes of ammunition casings

-

5,200 troops

British forces aim to have sent back more than 3,000 vehicles or items of equipment, including aircraft such as helicopters, and more than 5,000 containers of material to the UK by the end of 2014.

However, the UK Ministry of Defence (MoD) says some will not be returning and will, instead, be sold on.

"Examples of equipment that has been, or is likely to be, sold off include empty surplus storage containers, deployable laundry units and surplus JCB off-road forklift trucks," an MoD spokesman says.

Chris Murray, of Agility Defense and Government Services, external, which is tasked with selling off the surplus, says they have sold well over 2,000 containers-worth of equipment and about 100 vehicles on behalf of the MoD - including Land Rovers, Tata pickups and two airfield de-icing machines.

What the US is bringing back

£3bn-£4bn

Cost of US withdrawal

-

20,000 containers of equipment

-

24,000 vehicles/major equipment

-

38,000 troops

So far, the US has shifted about 300,000 tonnes of equipment, but, like the UK, not everything will be coming back. Anything surplus to requirements, too badly damaged or too expensive to transport could be given away, sold on or scrapped locally.

A spokesman for the International Security Assistance Force (Isaf) - the Nato-led security mission in Afghanistan - said around 15,000 vehicles were scheduled to stay behind - to be used for the post-2014 mission, donated to the Afghan government, or scrapped.

Among them are about 1,600-1,700 US Mine-Resistant Ambush Protected vehicles or MRAPs - the $1m (£604,000), 20-tonne vehicle designed to protect soldiers in Afghanistan from improvised explosive devices, or roadside bombs, that have proved so lethal.

About 9,000 MRAPs will be shipped back from Afghanistan, but the rest will go up for auction at around $2,000- $5,000 each (£1,200-£3,000).

"If there are no takers, then they will be demilitarised, chopped up and sold for scrap," says US military spokesman Mark Wright. "If we don't need it we are not going to ship it back. But it is still not the most practical vehicle for the Afghans - it is maintenance heavy."

Military checkpoints and Forward Operating Bases used by the Isaf troops in Afghanistan are being closed down and handed over to the Afghan National Security Forces as they take over responsibility for security.

Non-military equipment, such as cubicles, desks, lockers, generators, computers and televisions, are left to Afghan forces that take over the base - if they want them. If they don't, they are removed and disposed of.

Some things are not up for grabs though, such as "war-like materials" and any equipment that could be used for human rights abuses.

Afghan scrap collectors transport a load of destroyed equipment from departing US troops in Kandahar

The US is already providing the Afghan forces with weapons, ammunition and vehicles through the Afghan Support Fund. But officials say that where possible, support equipment and weaponry shipped out for US units will be taken home.

Equipment that is returning will be moved out by air, land and sea - or a combination of these methods. Cargo planes such as the C-17 and C-130s or chartered 747s are loaded with everything from Land Rovers to Merlin or Chinook helicopters.

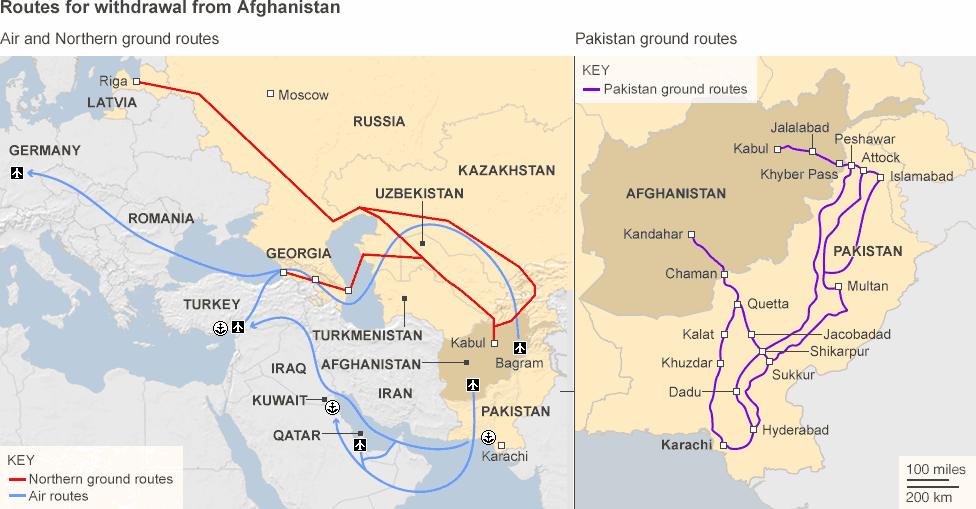

The three main routes are:

By air: Flights back to the UK or to intermediate ports in the Gulf and Mediterranean where the journey will continue by ship

By road south: The route through Pakistan to the port in Karachi is the easiest, but has been subject to delays and closures. The route was closed in 2011 after a Nato operation mistakenly killed Pakistani soldiers

By road and rail north: The Northern Distribution Network carries convoys, trainloads of personnel carriers and heavy vehicles through Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan to Georgia or on through Russia to Latvia

Francis Tusa, editor of Defence Analysis, external, says Afghanistan poses enormous challenges when compared with the withdrawal from Iraq.

"They are in an appalling landlocked country with ridiculously bad communications links," he said. "Compared to coming out of Iraq where you had motorways to ports in Kuwait, Afghanistan is a nightmare."

Mr Tusa says the route north has not been as successful as was initially hoped.

"All recent reports say the amount of kit going through the northern route is a fraction of that which had been hoped."

Containers and pallets will be loaded up and helicopters and vehicles dismantled to prevent theft.

"Before anything can be shipped it has to be stripped, which is a challenge in itself," explains US spokesman Mark Wright. "You have to strip the weapons off and anything else that could be pilfered. It is difficult to steal a 20-tonne vehicle, but you can steal parts off it."

Watch time-lapse footage of a Merlin helicopter being loaded into an RAF C17

Military officials say ammunition and explosives - or any items considered attractive to a terrorist or criminal organisation - would be flown out instead of going via land.

Mr Wright says the cost of the US withdrawal - or "retrograde" - is estimated at between $5bn and $7bn (£3bn-£4.2bn). But much depends on whether the land routes remain open. If the US lost the use of the Pakistan route, it would cost hundreds of millions of dollars to take the kit out by other means, he says.

Currently, the US is shipping about 3% of its cargo through the northern, Central Asia routes. This compares with about 42% via Pakistan.

The Central Asian route is also being used by the US to ship into Afghanistan - about a third of all supplies to support the ongoing operations.

The UK is also using this route to transport small volumes of cargo - to ensure the route is operational. It costs £7,000-£10,000 to ship one container through Central Asia by land.

As part of the deal to use the Uzbek leg of the route, the UK has agreed to give Uzbekistan £450,000 of military kit, such as car parts and trucks,

Troop numbers

Combat operations are due to end in Afghanistan on 31 December 2014. There are currently about 57,000 Isaf troops in the country, more than half of which are American.

The UK has about 5,200 remaining - from a peak of about 10,000 in 2011.

How many foreign troops stay on after the deadline is still undecided. A Bilateral Security Agreement between Afghanistan and the US, setting out the framework for US troops after 2014, remains unsigned.

It could see 15,000 foreign soldiers remaining, primarily as trainers and mentors for the Afghans, but also to conduct "counter-terror operations".

The MoD says that until the pact is signed, no decision will be made on the contribution from other nations. About 100 British troops will, however, continue their work as mentors at the Afghan National Army Officer Academy near Kabul.

Many US troops will fly out - the same way they flew in