New cross symbolic for Pakistan's Christians

- Published

Over the last year or so, on my way to work in Karachi I have noticed an unusually tall structure come up. Initially, it seemed like a massive pillar made of tonnes and tonnes of iron, steel and cement. It later took the shape of a giant cross.

The scaffolding-covered concrete structure stands just inside a cemetery, known as the Gora Qabaristan - literally meaning "a graveyard for the white people" in Urdu.

Located along a busy road bustling with traffic, it's one of the city's oldest and biggest cemeteries dating back to the British colonial era.

Over the years, the graveyard has been losing land to illegal settlements. Some treat it as a dumping ground for their garbage waste. Graves, with crosses and religious statues, are often vandalised here.

The cross is said to be one of the highest in the region and measures about 43m (140 ft). The man funding the construction, Parvez Henry Gill, a Pakistani Christian businessman, says he's building it as "a symbol of peace and hope".

The towering figure is aimed at countering the threats and despair that Pakistan's Christians have felt in recent years.

The Christian cemetery known as the Gora Qabaristan

Reliable figures aren't available, but activists say scores of Christians who could leave the country have done, for places like Canada and Australia. Others are supposedly looking to get out.

Christians make up a tiny minority of Pakistan's overwhelmingly Muslim population of 190 million. Estimates of their numbers vary. According to the country's last census, they total about 1.5% - but Christian leaders assert that 5.5% is closer to the truth.

Majority are descendants of those who converted from Hinduism under the British Raj

Most converted to escape their low-caste status and many are among the poorest in Pakistan

Targeting of Christians has been fuelled by strong anti-blasphemy laws and anger over the US-led war in Afghanistan

Attacks and persecution

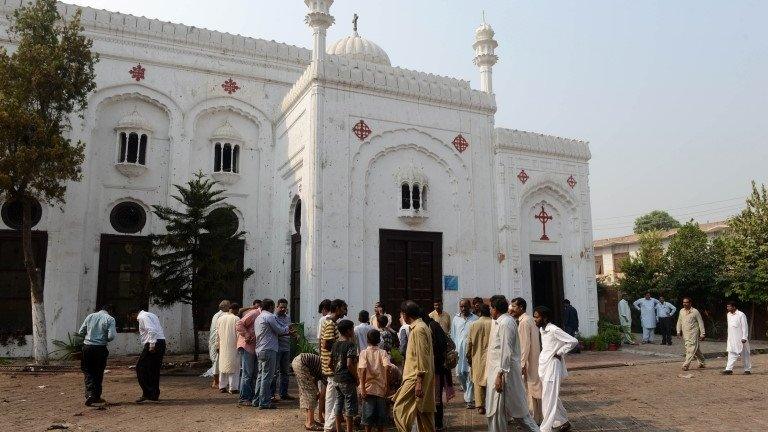

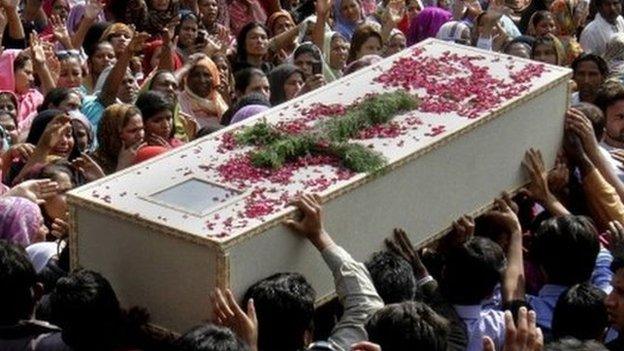

One of the worst militant attacks on the country's Christian minority came in September 2013. At least 80 people were killed when a church was bombed in the north-western city of Peshawar. The atrocity sent shockwaves across the community.

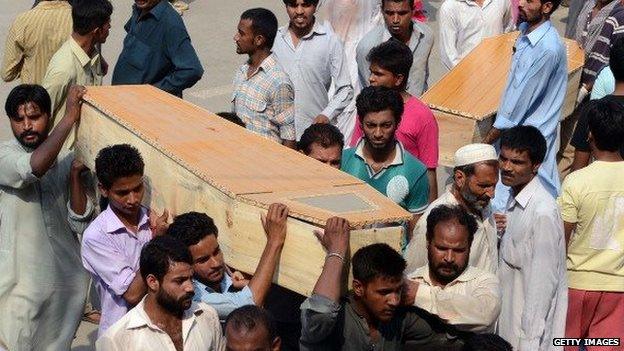

Pakistani Christian mourners carry the coffins of relatives killed in the 2013 Peshawar church bombing

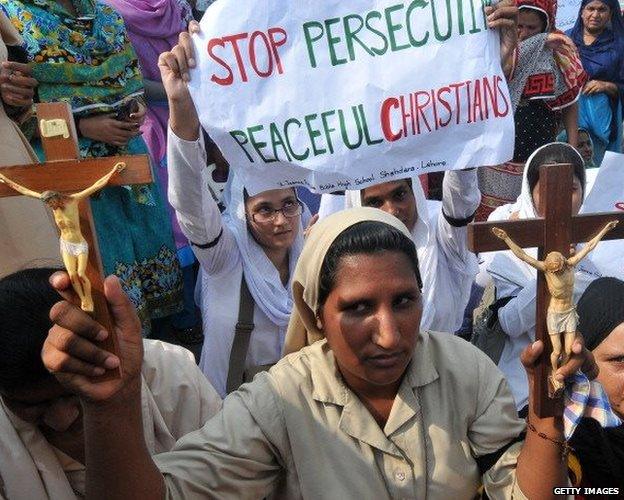

The attack sparked protests among Pakistan's Christians

More recently, in March 2015, suicide bombers again targeted churches, this time in the eastern city of Lahore, killing 15 people.

Such acts of mass murder bring about an enhanced sense of insecurity within the community. But it's the everyday discrimination and fear of persecution - often in the name of blasphemy - that has forced many Christians to seek asylum elsewhere.

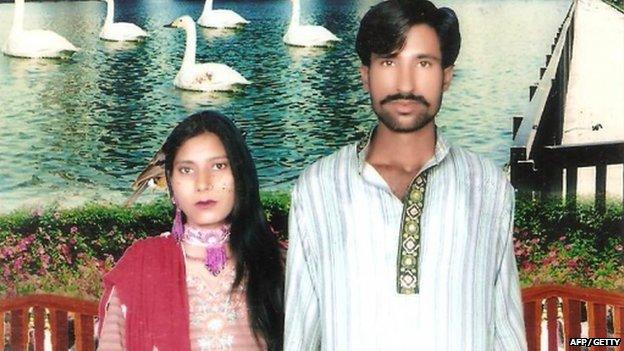

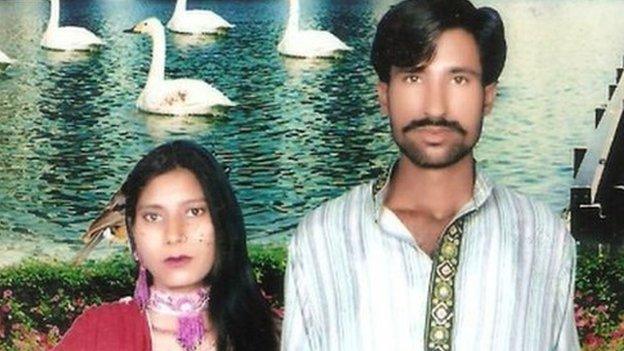

The lynching of a Christian couple - Shehzad (later identified as Sajjad Mesih) and Shama - by an angry mob in November 2014 in Kasur district, Punjab, showed how a mere allegation of blasphemy could be enough to kill people.

The victims were poor brick kiln workers who were beaten and burned alive in the presence of hundreds of onlookers, including helpless policemen. Ten months on, 106 people have been charged, but 32 suspects are still said to be at large.

Shama Mesih was pregnant with her fifth child when she and her husband were killed

Stifled debate

Human rights activists say Pakistan's police and its criminal justice system fail its people generally, but religious minorities are often the worst affected.

Take the highly controversial case of Asia Bibi, a Christian mother of four convicted of blasphemy and given a death sentence.

She's always denied the charges. But it's taken her six years to reach the Supreme Court to appeal against her conviction. Last month, the court temporarily suspended her death sentence, but it's unclear how much longer she will have to stay behind bars while her case drags on.

Any criticism of the country's blasphemy laws is deemed unacceptable and potentially life-threatening.

In 2011, two government politicians - a liberal governor of Punjab, Salman Taseer, and a Christian minister, Shahbaz Bhatti - were shot dead for that reason. The murders stifled any debate on the abuse of the law, as the government of the day appeared helpless in the face of extremism.

Shahbaz Bhatti predicted his death in a video recorded four months ago

But it wasn't always like this.

Transformation

Christian leaders take pains to highlight their role in voting for Pakistan at the time of the partition of the Indian sub-continent in 1947.

Christians were also integral in their contributions to Pakistan's national life in its early days.

For example, Pakistan's first non-Muslim and most respected top judge of the Supreme Court was a Christian, Justice A R Cornelius.

The first editor of Pakistan's leading English language newspaper, Dawn, was a Christian man by the name of Pothan Joseph, appointed by none other than the founder of Pakistan, Mohammed Ali Jinnah.

Christians continued to play a leading role in the country's social progress, especially in promoting health and education.

As a child, I grew up listening to stories of my mother's convent education in the 1950s in Khairpur Mir's, a small city in rural Sindh province. When I was born, she insisted that she be taken to a missionary hospital in the nearby city of Sukkur because she "trusted the professionalism and diligence of the Christian nurses there".

Most Pakistanis agree that attitudes began to change in the 1970s as hardline Islamists started asserting their narrow, exclusive agenda.

By the 1980s, the country was in the grip of a military dictatorship of General Zia-ul-Haq. He went on to introduce a series of regressive laws in the name of "Islamisation".

Over the next few decades, long after Zia was dead, his Saudi-inspired version of Islam would effectively transform Pakistan from a tolerant, liberal country to a conservative Islamic society with little or no regard for religious and cultural diversity.

- Published28 March 2016

- Published21 May 2015

- Published17 March 2015

- Published16 March 2015

- Published1 September 2014

- Published4 July 2011