Canadian archaeologists hunt long-lost Arctic explorers

- Published

Capt Sir John Franklin and his entire crew perished in the frozen Arctic

It has been more than 150 years since Capt Sir John Franklin and his 128 men perished in the Canadian Arctic, their ships lost in one of the greatest disasters of British polar exploration.

Now, a Canadian archaeological team is en route to the Arctic in a fresh hunt for Franklin's ships.

Relying on 150-year-old testimony of indigenous Inuits and 21st-Century methods like sea-floor surveying, the team hopes to find HMS Terror and HMS Erebus and discover once and for all the fate of the men - who are believed to have succumbed to scurvy, hypothermia and even cannibalism before they perished in the frozen Arctic.

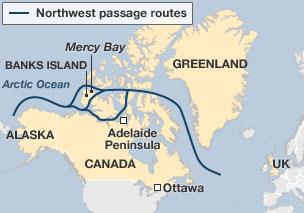

The expedition by Parks Canada, a Canadian government agency, comes amid Canada's increasing efforts to assert sovereignty over the waters of the Northwest Passage, which is increasingly navigable for longer periods during the summer.

This sea route is the same one Franklin and his men set out to find in 1845.

The expedition will also be the first to search for the ship sent to rescue Franklin, HMS Investigator.

Parks Canada underwater archaeologist Ryan Harris and his boss Marc-Andre Bernier have been pondering the fate of Franklin and his crew while examining maps of the Canadian Arctic at their Ottawa headquarters.

Aiding in their search are underwater archaeologists Jonathan Moore and Thierry Boyer.

Remarkably, the crew of the Investigator survived.

"The Investigator promises to tell its own stories!" says Mr Harris.

"Our job is to understand and make those objects speak," adds Mr Bernier, "and that's what's fascinating."

An explorer's 'obsession'

For centuries, the search for the Northwest Passage was an obsession of the world's naval powers and their finest polar explorers, who hoped it would shave thousands of kilometres off the European-Asian trade route.

Navigation of the passage would bring immediate fame, glory and fortune: the Royal Navy offered a £10,000 (£600,000 in today's money) prize for its discovery. But the route, if it existed, would pass through one of the coldest and most hostile places on earth: the Arctic.

Ryan Harris and Marc-Andre Bernier of Parks Canada

The ships left Greenhithe, England in 1845 "with incredible optimism", says Mr Harris.

A highly respected explorer, Franklin's vessels were at the cutting edge of naval technology: they were driven by propellers, the first used in polar exploration.

When the ships failed to return three years later, the Royal Navy sent out search parties.

The Investigator left Britain in 1848, ultimately making two attempts to find the Franklin expedition.

After failing to gain access to the eastern Arctic by going around Greenland - Franklin's route - the ship sailed around the Americas and steamed up the Pacific Coast, entering the Arctic from the western side.

The Investigator's crew risked being crushed by towering snow mountains while en route to Mercy Bay on Banks Island in the north-western Arctic, where they spent winters waiting for the ice to break up.

It never did. Running low on supplies and food, Capt Robert McClure and his men faced almost certain death. If it hadn't been for a note the crew had left on a cairn that was picked up by a sledge team sent from the HMS Resolute, another ship sent to rescue Franklin, they would probably have died.

Miraculously, the crew survived to be the first Europeans to traverse the Northwest Passage - by sledge and by ship - sharing the Royal Navy's £10,000 prize.

But Franklin's fate remained a mystery.

'Horrific conclusions'

Only later, in 1854, did the explorer John Rae - who was trained to survive in the Arctic by the Inuit - draw some horrific conclusions.

From Inuit testimony and items of the crew he acquired, including forks and spoons, he concluded the freezing, starving crew had died - some resorting to cannibalism.

Rae collected a £10,000 reward offered by the Royal Navy for discovering Franklin's fate, but was spurned by British society for his unpalatable reports.

Another cairn note, left by the Franklin crew and found by the Irish explorer Francis Leopold McClintock in 1859, described the death of Sir John Franklin and the deteriorating conditions for his men. The evidence supported Rae's conclusion and the Inuit testimony he had gathered.

Despite the disastrous Franklin Expedition, the Royal Navy's polar exploration played a huge role in advancing knowledge about the Arctic and was crucial to Canada's own history, Mr Harris explains.

"They went a long way to map the Canadian archipelago," he says.

"The various English expeditions in search of the Northwest Passage underpin Canada's sovereignty in the Canadian Arctic.

"Great Britain could assert ownership of the Arctic Archipelago - and of course they passed it on to Canada" when the country gained independence from Britain, he says.

But Canada's assertions of Arctic sovereignty, including its claim to the Northwest Passage waters, have been challenged in modern times, particularly by the US.

Famously, in 1985, the US Coastguard icebreaker Polar Sea stirred up a diplomatic row when it failed to seek permission from Canadian authorities to pass through the passage.

Asserting sovereignty

As Arctic ice retreats and makes the passage waters increasingly navigable - although still blocked by ice much of the year - Canada's neighbours want to know just how many millions of metric tonnes of oil, gas and minerals lie below the surface.

In response, Canada has stepped up efforts to assert sovereignty over what it sees as its part of the Arctic, including, beginning 1 July, requiring ships to register before passing through those waters.

Mr Harris will use a Twin Otter plane to help his team reach their destination

One outstanding issue from the early days of Arctic exploration is that Arctic waters have not been completely charted, a problem that preoccupies Mr Harris.

"We know much more about the surface of Mars than we do about the underwater topography of the central Arctic," he says.

Mr Harris and his team will fly in a small Twin Otter aircraft and finally by helicopter to reach their first destination, on the near-freezing shores of Mercy Bay - where they will set up a campsite.

Remote and far from rescue, they will be accompanied by an indigenous Inuvialuit guide, who will keep an eye out for polar bears and monitor the famously volatile Arctic weather. Mr Harris is encouraged by reports that ice has broken up early in the area.

Searching for 'clues'

The archaeologists will be using sonar equipment to locate the Investigator, basing their search on charts left unfinished by Capt McClure and the crew of the ship.

Another clue to the location of the wreck will be the large cache of coal and provisions left by the Investigator on the shores of Mercy Bay.

The archaeologists say the search for the vessel was inspired by the cache. It has long been known to the Inuvialuit, whose ancestors visited it and harvested metal items that would have been exotic and highly useful.

The Investigator's crew would have been the first white men encountered by the Inuvialuit.

After Mercy Bay, the archaeologists will fly more than 1,000km (621 miles) east to a Canadian icebreaker, the Sir Wilfrid Laurier, where they are to join a hydrographic team surveying the sea floor. The group will focus its search for HMS Erebus and HMS Terror on the ocean floor west of the Adelaide Peninsula.

If the ships are found they will remain British property, but in Canadian care.

"If we are so lucky as to find one, that would go a long way to vindicate and validate the Inuit version of events," Mr Harris says.