US border violence: Myth or reality?

- Published

With Arizona's controversial immigration law due to come into effect this week, the national debate over border security is poised to reignite

Fears over Mexican drug cartel violence near the border are fuelling the debate over immigration and border control, but is the idea that the killings are spreading into the US just a myth?

Once upon a time, Spanish settlers named the crossing El Paso Del Norte - the pass to the north.

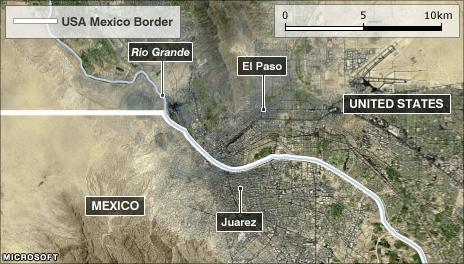

The border city of El Paso, Texas, lies along the Rio Grande, in the chasm between two inhospitable mountains.

Each day, thousands of people in cars, buses and on foot cross the short bridge that connects El Paso with its Mexican sister city, Juarez, one of the world's most dangerous places.

In the past two years, more than 5,000 people have been murdered in Juarez as drug-related crime has soared.

Politicians, including Texas Attorney General Greg Abbott, tend to portray border towns as being pushed to crisis point.

"We see this crime on a daily basis. The federal government must respond more effectively, step up their enforcement and protection of the border before more American blood is shed," Mr Abbott told Fox News.

"It is more dangerous to walk the streets of Juarez, a few blocks from El Paso, than it is to walk the streets of Baghdad. There is a very serious problem that is beginning to bulge at our borders and put American lives at risk."

In mid-July, President Barack Obama ordered 1,200 National Guard troops to patrol the border, just days after a car bomb exploded in northern Juarez, very near El Paso.

Texas Governor Rick Perry called that deployment "grossly insufficient". Many politicians are calling for even more troops.

But the mayor of El Paso, John Cook, isn't one of them.

Second safest city

"The reality is we really don't need the help on this side of the border. We probably have every kind of federal law enforcement agency that you can think of. We're an extremely safe community," Mr Cook says.

Despite Juarez's murder toll, in El Paso, local authorities have recorded just two murders this year. In 2009 there were 11.

"Logically it would seem that if you have violence on one side of the border then you're going to have spillover on the other side," says Mr Cook. "But the reality is that we don't."

According to FBI crime statistics, El Paso is the second safest city in America. Crime rates there have dropped 36% over the past 10 years.

Other cities close to the border, including San Diego in California and Phoenix in Arizona, have similarly experienced declines in violent crime.

Over the same period, federal agencies have beefed up their presence along the border, and a 2,000-mile fence is slowly being constructed.

The fence near El Paso is 16-18 feet (4.9-5.5m) high, made of rust-coloured steel mesh. There are 2,700 border police in this sector, monitoring the border day and night, and a raft of FBI, CIA and drug enforcement agents.

Mr Cook questions the need for more troops, given that current border security levels appear to have been effective at containing drug violence south of the border.

Additionally, both he and local border enforcement officials believe that the leaders of drug cartels do not believe it is in their interest to bring the violence north.

Drug barons know that the response from the US government would be swift and heavy, and further hinder their ability to smuggle drugs into the lucrative American market.

Locals worry that with an even heavier security presence in town, El Paso risks becoming like Cold War Berlin, a riven city, its character disrupted by an imposing divider wall.

They believe politicians who don't live on the border fail to appreciate the deep interconnectedness of cities like Juarez and El Paso, which Mr Cook describes as "one city joined by a border".

So with crime rates declining and the border stable, how has this relatively safe Texan city found itself in the centre of a political firestorm over border violence, and the Obama administration's plans to deal with it?

Politics and fear

Border historian David Romo says it is a pattern. He's seen politicians fanning fears about the border before.

The first calls to build a border fence in El Paso to secure the city came in 1908. Back then, the fear was Chinese immigrants. In World War I, politicians worried about Germans streaming across.

A variety of surveillance methods are used - helicopters, 4WDs, checkpoints, dogs and horses

These days, it's Mexicans who fuel unease. Mr Romo says that during times of economic distress, the border and the immigrants who cross it are used as scapegoats. He believes history is repeating itself, and politicians are using the same rhetoric they have for decades.

"It happens that every time an election year comes up, they know that creating fear and hysteria about the border will drive a wedge," Mr Romo says.

"In some ways it's cheap vote-getting. There is this cycle of kind of nativist hysteria that is very profitable for politicians. Nothing gets votes like the politics of fear."

Mr Romo says he's not seen evidence of violence infiltrating the El Paso community. He argues that the immigrants who make a new life across the border are motivated to act within the law because they fear being deported.

While Arizona Governor Jan Brewer blames immigrants, illegal and otherwise, for violent crimes and burglaries, Mr Romo says that, ironically, those immigrants have the most incentive to be law-abiding. They don't want to draw attention.

Bleak outlook

Although fears of spillover violence aren't substantiated by crime data, they are having a real impact on the economy of El Paso.

Parts of Juarez are poor - El Pasoans say they see Juarez locals washing clothes in the river

"From an economic development perspective, it's been very negative for us," Mr Cook said.

He has difficulty convincing new businesses to set up in El Paso because of the violence in Juarez. The first question he gets asked in business meetings is usually "is it safe?"

"They don't pay attention to the fact that we are the second safest large city in the United States," he says.

"We've had people who have looked to locating here with their companies and we have to convince them that it's a safe place. They almost don't believe you."

The longer the violence continues in Juarez, the bleaker the outlook becomes for El Paso, despite its impressive safety record.

For now, there's little more Mayor Cook can do but wait.

- Published23 July 2010

- Published7 July 2010