BP says 'static kill' to stop oil leak was successful

- Published

BP pumped mud into the well for eight hours during the procedure

BP says the "static kill" of its ruptured Gulf of Mexico oil well has worked, a big step towards sealing it.

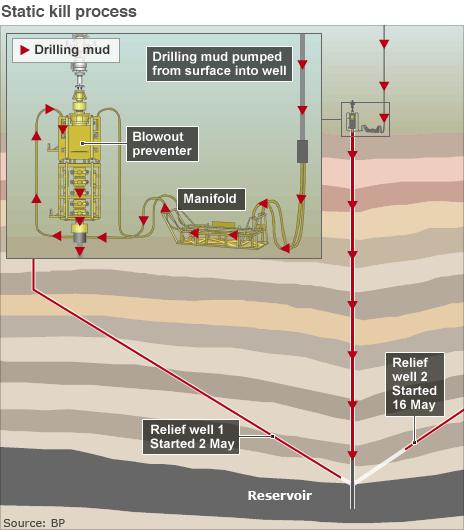

In the procedure, special drilling fluid known as mud is pumped into the well, forcing the oil back down.

BP said well pressure was being controlled by the pressure of the mud, which was "the desired outcome".

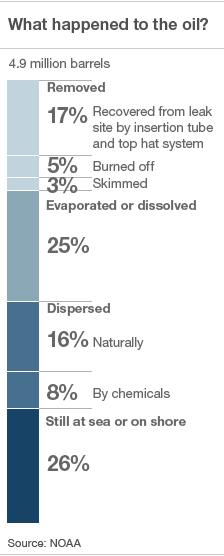

Meanwhile, a government report due to be published today is expected to say that only 26% of the leaked oil poses any further danger to the environment.

About three-quarters of the escaped oil has already evaporated, dispersed, been captured or otherwise eliminated, according to a new analysis by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (Noaa), reported in the New York Times.

'Significant milestone'

BP began pumping mud into the well from vessels on the surface at 2000 GMT on Tuesday, in order to counter the pressure from the oil pushing out of the reservoir below the seabed.

BP spokeswoman Sheila Williams said the drilling mud was currently holding the oil down.

"The well appears to have reached a static condition - a significant milestone," she said.

"The well is now being monitored, per the procedure, to ensure the well remains static. Further pumping of mud may or may not be required depending on the results observed during monitoring."

The well ruptured after an explosion on the Deepwater Horizon drilling rig in April which killed 11 workers.

The flow ended on 15 July, when BP closed a new cap it had put on the well. It could eventually seal the mouth of the well with cement.

The US government says the well leaked 4.9 million barrels of oil before being capped last month, with only 800,000 barrels being captured.

But it is expected to announce on Wednesday that only 26% of the oil released was still in the water or onshore in a form that possibly could cause new problems.

Most of that oil is either a light sheen at the surface or in a dispersed form below the surface, and federal scientists believe both forms are breaking down rapidly, the New York Times reports.

Fears that a huge underwater accumulation of oil might eventually surface and pollute beaches are therefore unfounded, the report suggests.