US primary elections: Do political endorsements matter?

- Published

Sarah Palin's endorsement brought would-be South Carolina governor Nikki Haley much attention

Judging by the press coverage, the US primary elections on Tuesday were as much about the powerful political celebrities who endorsed the candidates as the candidates themselves.

The battle between Michael Bennet and Andrew Romanoff to be the Democratic nominee for the US Senate in Colorado seemed as much a proxy showdown between their presidential supporters: Barack Obama and Bill Clinton respectively.

With Mr Bennet triumphant, it seemed Mr Obama's blessing was more potent.

Or did it? Are endorsements pivotal game-changers, or merely incidental?

'Vote cues'

For political analysts, the answer is complicated. For the most part, endorsements, regardless of how important the benefactor is, are of limited use when voters step inside the polling booth.

But in certain circumstances they can profoundly alter a race.

Stuart Rothenberg, editor of non-partisan election analysis newsletter the Rothenberg Report, puts it this way: "Endorsements matter when the voters don't know anything else about the candidates."

He says that when candidates are well-known or voters seem very engaged with a race, there are other "vote cues" or factors that matter significantly more.

That perhaps explains why President Obama's endorsement has been far from decisive over the past year, even holding little sway among those Democratic voters with whom he has remained extremely popular.

President Obama very publicly threw his weight behind New Jersey Governor Jon Corzine, Massachusetts Senate candidate Martha Coakley and Pennsylvania Senator Arlen Specter, all of whom lost.

But each of those races had intensive media coverage and unique issues which crowded out the importance of an endorsement.

In races where voters are paying little attention - such as mid-terms or local elections - endorsements matter more, even if they don't necessarily yield new votes.

Palin appeal

For a candidate struggling to find ground in a crowded primary field, or an insurgent candidate taking on an incumbent, an endorsement can be powerful.

In the competitive race to be governor of Georgia for example, Sarah Palin's active campaigning for Karen Handel buoyed the candidate and turned people out at her public events.

Ms Handel conceded the race on Wednesday, but it was very close, with just 2,500 votes separating her and her opponent, Congressman Nathan Deal.

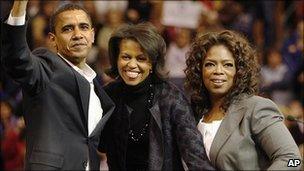

Oprah Winfrey's early support lent plausibility to Barack Obama's presidential aspirations

Mr Deal matched Ms Handel's conservative credentials by receiving endorsements from the NRA (National Rifle Association) and former presidential candidate Mike Huckabee. So, like the Colorado race for the Democrats, the Georgian Republican primary has become shorthand for the internal power struggles of the party.

The two are neck-and-neck in a run-off election that is currently too close to call.

Ms Palin's endorsement of Nikki Haley in the South Carolina governor's contest earlier this summer is another case in point.

Mr Rothenberg says Ms Haley was having difficulty breaking out in a field that included well-known local politicians like the lieutenant governor.

"The endorsement was significant in getting her a lot of publicity in the state," he says. It yielded significant press coverage and brought Ms Haley to the attention of Ms Palin's myriad devoted fans.

Michael Dimock, an associate director with the Pew Research Center, has found that Mrs Palin has a fairly unique appeal.

According to Pew's research, external, many more people say that a Palin endorsement would make them less likely to vote for a candidate than those who say the endorsement is a positive factor.

But their polls also suggest that for people who are drawn to Mrs Palin, her endorsement counts a great deal.

"The intensity of feeling really matters," Mr Dimock says. "The people who like Sarah Palin are right now very mobilised and active people. An endorsement from her carries a stronger credibility and intensity from that very active part of the electorate."

Mrs Palin's endorsement has a brand-like power for certain Republicans, who see it as a proxy for her particular set of conservative values. She helps them connect the dots.

"Palin matters when you have lots of candidates in the race and voters are scratching their heads and they can't quite figure out which one they want. She appears to be the cue that they use," Mr Rothenberg says.

No ordinary Joe

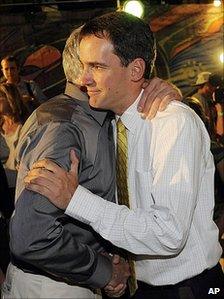

An endorsement alone rarely sways votes, but it can lend credibility to a relatively unknown candidate. That is why Bill Clinton's backing mattered to Mr Romanoff's campaign - even if it didn't result in a win, it helped make the race competitive.

Andrew Romanoff lost despite being endorsed by Bill Clinton

His opponent, the incumbent Mr Bennet, had the support of most of the Democratic Party establishment, including Mr Obama. Having an elder statesman such as Mr Clinton vouch for his candidacy helped Mr Romanoff establish his viability as an alternative.

"In cases when you have candidates who are not well-known to the voters individually, those endorsements lend an air of seriousness to a candidate that people may not be familiar with," Mr Dimock told the BBC.

"When a major national figure endorses you, you're obviously not just some Joe off the street at that point."

But the timing of an endorsement is often the secret to its success.

When Florida Governor Charlie Crist held out on endorsing a Republican presidential candidate until just days before the 2008 Florida primary, he maximised both the impact of, and interest in, his choice, John McCain, who ultimately won the nomination.

When television magnate Oprah Winfrey told the world in May 2007 that she was backing a little known Illinois senator, Barack Obama, for president, almost 70% of Americans told Pew that her endorsement, external mattered little to them.

But, at a time when Hillary Clinton was the odds-on favourite for the nomination, Ms Winfrey's seal of approval generated a frenzy of media attention, lending his candidacy a new sheen of plausibility.

She also held fundraisers for Mr Obama - another perk of having wealthy supporters, and one that matters early in a race.

But once an endorsement has bought media attention, it's up to the candidate to capitalise on it.

"It will get the candidate some attention but then that candidate must have the skills to sell him or herself to those voters who are now going to be looking more closely," Mr Rothenberg says.

Mr Dimock says that the scenario in which endorsements matter most is in the case of a referendum.

Often, the issues under consideration are complex and the wording of the question can be confusing.

For example, a proponent of gay marriage in California would have had to vote "no" on Proposition 8, the 2008 ballot question which would have permitted gay couples to marry in that state.

A "yes" vote on Prop 8, as it is known, would mean the voter favoured restricting marriage to between a man and a woman.

In the case of a referendum, an endorsement from an organisation with a clear agenda, for example Friends of the Earth or the Human Rights Campaign, is usually a trustworthy marker for voters.