Viewpoint: Book burning is no great trick

- Published

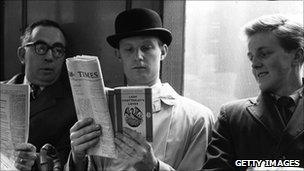

Books were burnt by the Nazi regime in 1933

When Hillary Clinton announced in a recent news conference that she hoped the proposed burning of the Koran by a small-town pastor in Florida wouldn't get too much attention, everyone laughed indulgently, Hillary included.

Nothing raises the hackles like an old-fashioned bonfire, but timing is everything.

The high-school kids filming themselves burning Lord of the Flies for YouTube don't terrify us but "International Burn-a-Koran Day" is invidious enough to get our attention.

In Florida, pastor Terry Jones has laid his symbolism bare announcing that his proposed Koran burning is meant to serve as a reminder of 9/11, because the book "reveals the true colours of Islam," and he wanted to see what could be done "to really show the dangers of what happened that day."

Such a statement is disconcerting enough, but it's got nothing compared to the statements on the internet. Anyone who imagines that the efforts of Mr Jones can easily be dismissed should search for one of the online videos about the forthcoming event and read some of the comments being posted by fans and opponents alike.

It is no great trick to burn a book, but many critics are haunted by the possibility that Mr Jones will incite fierce anti-American sentiments around the world.

At the same time, there is a due reluctance to call for the burning to be banned, and be caught curtailing freedom of speech. Certainly the authorities in the US will be reluctant to make any overt ban: in the past, the preferred option has been to have the local fire department refuse to issue a permit for an open fire. As this implies, for us moderns, fires are low-rent spectacles, and a book burner is more likely to be locked up for environmental crimes than for perceived fascist tendencies. At least we are all much too sophisticated to start making any comparisons with the Nazi bonfires (see box).

Battle of the books

While censorship, broadly defined, exists in all countries, it is certainly true that America has a vexed relationship with the symbolism of the "book", and its fair share of censors.

There have been many pitched battles, usually in the shadows of the local town or school library. In Chicago in the 1920s the mayor "Big Bill" Thompson started a movement to have "pro-British" books taken outside and burnt, while in St Louis in 1939 three copies of the Grapes of Wrath were destroyed by librarians because of "vulgar words". Slaughterhouse Five routinely gets dumped from school libraries even now for the same reason.

These fires play on the way in which people identify with books. On a personal level, we are forever being asked to name our favourite book, and the answer is considered a guide to someone's identity, as reliable as knowing their favourite colour or their star-sign. This might work if the answer is Mein Kampf or Lord of the Rings, but otherwise is pretty sketchy. Similarly, we are always being asked what books we would take to that desert island.

The issue of book burning also speaks to our reluctance to be considered a censor. This reluctance can even be seen in most pro-censorship writings, nearly all of which have loopholes: even staunch proponents of a free press are often uneasy with the monsters they are making.

Emotional attachment

Among the book-rich, there is a wariness about exhibiting too much emotional attachment to just one book. We often associate such passion with adolescence (a teenager reading Twilight), ignorance (a grown-up reading Twilight), or madness (John Lennon's killer Mark David Chapman on the stoop reading Catcher in the Rye).

In 1960 the Lady Chatterley's Lover became the subject of an obscenity trial in the UK

It is not surprising that these personal fears and superstitions about books can have some significance to a larger political event. What is unusual about Mr Jones is his target: most small town preachers are more worried about the kids reading Harry Potter or listening to Elvis LPs, rather than a grand political statement. That is, most religious-inspired bonfires have more in common with the book burning scene in the New Testament, in which the good people of Ephesus voluntarily renounce their own books, burning them to show their sincerity (Acts 19:19).

It is a truism to say that working out which books are being banned is an easy guide to understanding the society that is banning them. The Nazis banned communists and Jewish authors, McCarthy railed against the Reds, repressed old Britain struggled with Lady Chatterley, and so on. And this leads to a second truism: the censors of yesterday, no matter how sinister, always seem quaint.

What is frightening is not so much Jones and his friends, as they bridle under the weight of media scrutiny, but how the event is being used as a stalking horse in the great clash of symbols. If people can't get past this level of brute symbolism, it's hard to stay optimistic. Books will drive us mad, but burning them won't help.

Matthew Fishburn is the author of Burning Books, a chronicle of book-burning through the ages

- Published7 September 2010