What exactly is the Tea Party?

- Published

The Tea Party has become an umbrella group for many different causes and angry protesters, making it hard to pin down

Conservative activists calling themselves the Tea Party roared on to the political scene in in 2009. They have propelled strictly conservative, anti-establishment candidates to victory in numerous Republican primaries this year.

But some of their candidates are so outside the mainstream that the Tea Party have ended up helping Democrats to win those seats. To many Tea Partiers, that doesn't matter.

"What use is a Republican to us, if all they do is vote with Democrats?" Christina Botteri, one of the founding members of the Tea Party movement, told the BBC.

Such attitudes have flummoxed Republicans and political pundits who still seem unsure what exactly the Tea Party is and it wants.

Birth of a movement

Perhaps the most important thing to understand about the Tea Party is that, in some ways, it defies traditional categorisations.

John McCain is set for a rough ride from the Tea Party movement

It was founded amid a groundswell of populist anger over government bail-outs of failing banks, insurers and auto companies following the economic meltdown of 2008.

Most Tea Partiers agree that a rant by CNBC Business News editor Rick Santelli, broadcast live on television, was a catalysing moment.

Standing on the floor of the Chicago Mercantile Exchange, Mr Santelli railed against government bail-outs for those he believed had made poor investments, saying such aid was "promoting bad behaviour".

Don't help these "losers" with their mortgages, he shouted, as traders cheered him on in the background.

His sentiments didn't just strike a chord, they became a call to action. Less than 10 days later, Santelli-inspired protests against "big government" occurred in 40 cities across America.

This nascent group of conservative activists called itself the Tea Party.

"We realized that government spending without the will of the people is a form of taxation without representation," says Ms Botteri, referencing the motto of the original Tea Party protest in Boston, when early American colonists threw taxed British tea into the harbour.

Focus on the economy

The modern day Tea Party has three central tenets: fiscal responsibility, limited government and free markets.

One of its defining characteristics is vociferous anger at Congress and the White House. Mistrust of politicians, government and the media runs deep.

Although many members hold deeply conservative social beliefs, the Tea Party is expressly and steadfastly economic, not social, in its outlook.

"They may be socially conservative personally on issues like abortion or gay marriage, but they think the Republican Party stopped being the party of fiscal conservatism when it became so obsessed with social conservatism," says New York Times journalist Kate Zernike, author of Boiling Mad: Inside Tea Party America.

The Tea Partiers are as disillusioned with George W Bush's big-spending Republicans as they are with Barack Obama's Democrats.

They naturally align with Republicans, but they are displeased with the party: many think it has deserted them.

"It's one of the common misperceptions that the Tea Party and the Republican Party go hand in hand," Ms Zernike told the BBC via e-mail. "In fact, they're fighting hand to hand in many parts of the country."

'It's an idea'

The Tea Party has no aspirations of becoming an official third party or anything approximating a formal political institution. Its members seek to influence existing parties.

It is interested in principles, not policy prescriptions.

Sarah Palin is popular within the Tea Party, but she is not its leader

"The Tea Party movement, much like America itself, is an idea," says Ms Botteri. They know what they are against, but they don't all agree how to implement the ideas they are for.

The Tea Party is leaderless. Although Sarah Palin and Fox News personality Glenn Beck enjoy wide-ranging support within the Tea Party, they do not speak for or lead the movement.

It is decentralised - not so much an organisation as a network of small groups with a loose affiliation to similar fiscal principles. It has no charter or by-laws.

These groups are localised, each have their own identities and priorities. That makes the movement exceedingly hard to pin down.

These organisational decisions are as much practical as they are tactical.

"Having a single hierarchical structure makes a clean easy target for the progressive left to apply their usual tactics of freezing, isolating and ridiculing," says Ms Botteri.

Ms Zernike believes the decision to steer clear of controversial social issues, even though many in the group speak in inflammatory terms about topics like immigration, is also strategic.

"They think that they can attract more people if they don't talk about polarising issues," she says. "As someone said to me, the more planks in your platform, the worse off you are: planks become splinters."

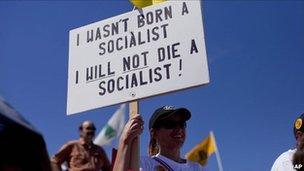

Tea Party members are angry at Washington and many believe Barack Obama's policies are socialist

Demographically, several polls show that the Tea Party is overwhelmingly white and older than 45, and more likely to be male.

The group has been accused of racism and xenophobia, allegations most members vehemently deny.

Still, many do not believe President Obama is an American, and Tea Party protesters were accused of hurling ugly epithets at black and gay members of Congress before last year's vote on healthcare reform.

One group erected a billboard in Iowa comparing Mr Obama to Hitler and Stalin.

Technological triumph

Most of the original members met using Twitter. Their low-budget nationwide organising was unthinkable in the days before Facebook, e-mail and free conference-calling.

This historic capacity to be networked with like-minded people has been a profound experience for many Americans.

Because of that, Ms Zernike characterises the Tea Party as a cause rather than a movement.

"The people I spent time with for my book talk about this as the most important thing they've done with their lives. It's given them community and a cause - the social bonds are very strong, and in many cases they're a motivating factor."

But perhaps the most interesting aspects of the Tea Party have yet to be seen. What will it do with any electoral success it has? And will those social bonds be sustainable when the economic stress gripping America eventually abates?