Is Teresa Lewis an unusual death row case?

- Published

Virginia executes more prisoners than most other US states

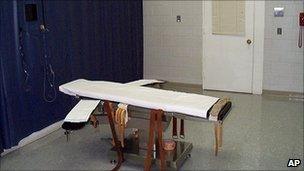

Virginia is due to execute a woman, the first in the US state since 1912 and the first anywhere in the country for five years. But why is the execution of a woman such a significant event?

Teresa Lewis's planned execution has been publicised everywhere from the UK to Iran.

Her case is unusual for three reasons.

Lewis plotted with two men to kill her husband and stepson, leaving the door of their home open and buying guns and ammunition for the killers.

She pleaded guilty and was sentenced to death. The gunmen Matthew Shallenberger and Rodney Fuller only received life sentences.

With Lewis's IQ measured at just 72, both her current legal team and death penalty opponents have suggested it is wrong to execute her and wrong to think she is likely to have been the driving force behind a plot.

Her legal team accuses Shallenberger, who killed himself in prison, of being the mastermind and of manipulating Lewis, with whom he had an affair.

But there is no doubt that what interests many people most about the case is the mere fact of Lewis being a woman.

'Extremely rare'

Women are not often executed in the US.

The statistics are striking, notes Victor Streib, professor of law at Ohio Northern University and a student of female death penalty cases for 30 years.

From 1 January 1973 to 30 June 2009, 8,118 people were sentenced to death in the US. Only 165 of those were women, 2% of the total.

Teresa Lewis has an IQ of 72

In the same period, of the 1,168 executions that have taken place, only 11 have been of women.

"The death penalty for women is extremely rare," says Prof Streib. "They tend to be screened out."

But they commit 10-12% of capital murders, says Prof Streib.

Historically, he notes, judges would openly say that the death penalty was not an option because the defendant was a woman. Now such a statement would be unthinkable, but there may be a hangover from earlier attitudes.

"We are more likely to believe a woman is mentally disturbed or under the control of a man, than a man," says Prof Strieb.

He wonders whether the apparent bias in sentencing could be because of cultural attitudes in law enforcement or even in the wider public.

Lenient treatment

"I think it's fair to say that when the public thinks of the death penalty they almost always get this image of an evil man."

David Muhlhausen, senior policy analyst in the Center for Data Analysis at The Heritage Foundation, suggests there is a bias in favour of women in the system.

"There is ample research women are treated more leniently for equivalent crimes.

"People's bias is that women are more sympathetic. If you look at death row cases, the overwhelming majority are men. Every time there is an upcoming execution of… a woman, it makes more news."

But as a piece in Slate, external suggests, citing a study on gender discrimination, external, there could still be a form of anti-female bias, with women receiving death sentences for categories of murders that men would not.

To these critics, women are sentenced to death for domestic murders as their crime is seen as egregious because of the contradiction of the stereotypes of female nurturing.

Lewis had sex with at least one of the killers, also allegedly offering the prospect of sex with her 16-year-old daughter as bait, and betrayed her husband, all motivated by financial gain.

Protective role

"Women tend to kill a member of the family. Men are much more likely [than women] to be involved in a stranger killing," says Prof Strieb.

This might help explain how someone like Lewis could be sentenced to death.

"There is a kind of a play on the notion that you expect women to protect the family and she is paying to get rid of the family," argues Prof Streib.

But for some opponents of the death penalty, the mere fact of Lewis being a woman is not the main issue.

Her low intelligence is a key issue, says Diann Rust-Tierney, executive director of the National Coalition to Abolish the Death Penalty

"That is a very big part of her claim. That she is a person of diminished capacity and shouldn't be subject to the death penalty.

"The people who actually committed the killing were serving a life sentence. Far from being the person who was most culpable, she was a puppet in a scheme. The injustice is striking."

But, with fewer than 50 people executed every year in the US out of the thousands of murderers caught and sentenced, and with different attitudes from state to state, there can be cases that seem inconsistent, says Prof Franklin Zimring, of the Berkeley School of Law.

"When you start with that kind of mathematics you come up with arbitrary outcomes.

"If you are looking for the most culpable 50 you wouldn't pick a lady with an IQ of 72."

Some of those who have taken an interest in Lewis's case have questioned why the issue of her low IQ was not forcefully raised at her trial.

But for supporters of the death penalty, such arguments do not hold water.

"Whether or not she was somebody who had a high intelligence or a low intelligence, she still committed a serious crime," says Mr Muhlhausen.