Why healthcare reform has been a tough sell

- Published

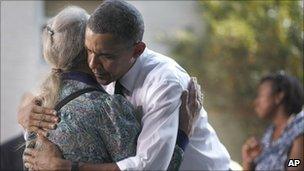

Mr Obama spent the six month anniversary of the bill with people who have felt its effects

Six months after the most significant overhaul of the US healthcare system in decades passed into law, President Obama is still trying to convince Americans of its merits.

Mr Obama marked the bill's anniversary at a suburban home in Virginia, surrounded by individuals who had felt its benefits.

But a majority of Americans still appear impervious to his attempts to persuade them that the bill will change their health care system - which Americans almost universally agree needs fixing - for the better.

Much of the bill has not been implemented, and will not be for some time. Regardless, polls indicate, external that support for it is declining - an average of recent polls shows around 40% in favour of the bill and 48% opposing the bill.

Those numbers are a serious political challenge for Mr Obama just six weeks before the mid-term congressional elections.

Sceptical public

"Sometimes I fault myself for not being able to make the case more clearly to the country," Mr Obama told the small gathering in Virginia on Wednesday.

He noted that the escalating costs of US healthcare were a main driver of the spiralling government deficits that so many Americans purport to worry about.

"Healthcare was one of those issues that we could no longer ignore," Mr Obama said. "It was bankrupting families, companies, and our government."

But a large tranche of the American public doesn't seem to be buying that logic, particularly while the economy remains anaemic.

Despite repeated Democratic attempts to illustrate the draining effects of rising health care costs on the economy, many Americans still question why Mr Obama chose to focus on healthcare while they worried about keeping their jobs and staying in their homes.

Drew Altman, President of the Kaiser Family Foundation, a healthcare research and advocacy organization, says public opinion is split along partisan or ideological lines. In short, Democrats like the bill, Republicans don't.

When his organisation polls opponents as to what they don't like about the bill, the response is usually isn't about the bill's content. They're angry at the process or they're angry at the direction of Washington.

"For those who are against it, healthcare reform has become symbolic of bigger things they are angry at Washington for," Mr Altman says, noting widespread voter antipathy towards the nation's lawmakers.

Worries over change

Karen Davenport, Director of Health Policy at left-leaning think tank the Center for American Progress, says that some Americans are having trouble separating their views on healthcare from their general malaise about the state of the economy.

Democrats rejoiced when the bill passed after many months of negotiations

Ms Davenport also notes an odd phenomenon where particular initiatives receive widespread support - for example, preventing insurers from refusing to cover people with pre-existing conditions - but that does not translate into overall approval of the bill.

"Individual elements continue to be very popular in polls," she says, puzzled over why the bill seems to be less than the sum of its parts in the minds of Americans.

Mr Altman's explanation is that healthcare reform has become shorthand for views on government and, he says, "once you make something a referendum on government in our country it is hard to win."

Ms Davenport believes that Americans are wary of change.

"There is an anxiety about changing something as critical as how I get taken care of when I'm sick, particularly in a world where its clear that the system that we have is so fragile," she says. "We're still in the angsty, anxiety-laden transition period. We've not gotten to the point of implementing the bill and feeling happy."

Sticky charges

Republicans and their allies have relentlessly attacked healthcare reform.

Anti-reform groups have spent seven times more on television adverting than pro-reform groups in the last month alone, the news website Politco reports, external.

Many false charges have stuck, like the claim that the bill is a government takeover of healthcare (it is not - there is no government provision of care outside of the existing Medicare programme for older Americans) or there will be government "death panels" deciding who can get what sort of care.

Despite efforts by Democrats, including Mr Obama, to debunk these ideas, they seem to speak to a deeply held suspicion of government on behalf of some Americans who refuse to be dissuaded.

"Proponents are selling the law in a very hostile public opinion environment," Mr Altman of the Kaiser Foundation says.

Republican leaders have vowed to repeal the legislation when next they have the power.

A full repeal is unlikely, as Republican senators would need to find the 67 senate votes required to overcome the veto Mr Obama would no doubt sign.

A more realistic scenario is that if conservatives pick up seats in November, they will try to alter the bill, effectively repealing sections of it. For that, they would only need a filibuster-proof 60 votes.

Many Democrats too are distancing themselves from the bill, recognizing that, with a closely-fought election looming in November, opposition to healthcare reform may be the factor that tips the scales against them.

Such behaviour may seem peculiar to international spectators whose healthcare systems are run with significant government intervention.

"This is by any standard is a middle of the road, centrist legislation that builds on our existing system," Mr Altman says. "It must look awfully strange to people in other countries to see it be debated as though it's radical legislation."

- Published23 September 2010

- Published8 September 2010