Is the Facebook movie the truth about Mark Zuckerberg?

- Published

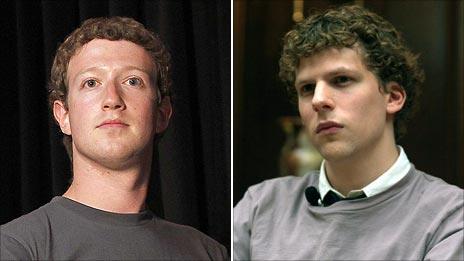

Mark Zuckerberg gets the Hollywood treatment

The Social Network movie portrays Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg as a socially-awkward, insecure, devious, ego-maniac, but is it the truth? And if not, is that a problem?

Film-makers have always played fast and loose with history.

From war films to grand swords-and-sandals epics, screenwriters have put words in the mouths of historical characters that may or may not have belonged there.

Most of us accept the idea that a scene in the life of a Napoleon or Henry VIII is necessarily fictionalised. But then there's The Social Network.

This tale of the founding of Facebook by Mark Zuckerberg and friends at Harvard University in 2004 is very recent history indeed. And it's tendentious, to say the least.

In it, Mark Zuckerberg - played by Jesse Eisenberg - is not a very nice person.

The film starts with him being dumped by his girlfriend as she lists his faults.

He then goes on a journey where he displays arrogance, contempt, and lashings of social envy on his way to becoming a billionaire.

But while the movie, written by Aaron Sorkin and directed by David Fincher, is already earning plaudits from film critics, technology writers who've had dealings with Zuckerberg have been lining up to pick holes in it.

Blogger Jeff Jarvis, author of BuzzMachine and the upcoming book Public Parts, for which he interviewed Zuckerberg, believes Sorkin has made too much of the story up.

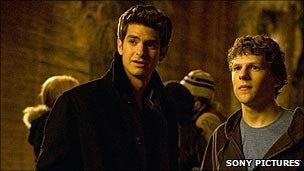

Eduardo Saverin is the 'goodie' in the film

"That's what the internet is accused of doing, making stuff up, not caring about the facts," he says.

The film is only "40% true", says David Kirkpatrick, author of The Facebook Effect: The Inside Story of the Company That Is Connecting the World.

"Zuckerberg is unbelievably confident and secure. And he is not snide and sarcastic in a cruel way, the way Zuckerberg is played in the movie," he says.

"A lot of the factual incidents are accurate, but many are distorted and the overall impression is false."

A key plank of the movie is that a major motivation for Zuckerberg in building Facebook was a break-up and the desire to impress the girl in question and achieve social acceptance. That's false, says Kirkpatrick.

"It is a fairly important point that he had a girlfriend during the whole time the movie is showing. The movie is presenting a sex-obsessed, desperate-for-the-attention-of-a-woman guy.

"But his motivations were to try and come up with a new way to share information on the internet."

And the idea that Zuckerberg would deliberately betray a friend is dismissed by Karel Baloun, author of Inside Facebook. Baloun spent a year between May 2005 and May 2006 as a senior engineer at Facebook, working closely with Zuckerberg for much of the time.

Mark Zuckerberg announced a $100m donation on the Oprah show

"It is fiction," says Baloun. "He really wanted it to be good for everybody. He wanted our hard work in Facebook to be rewarding."

The image of Zuckerberg as a socially inept nerd is overstated, his defenders say.

"He is socially awkward," says Baloun. "I'm amazed he has managed to be a CEO - he has had great coaching. When he sets his mind to improve himself he does."

Jarvis says Zuckerberg once was a deer in headlights but has improved.

"Sorkin goes as far as to make it a syndrome. [Zuckerberg] has that stare. But when I've sat down with him in person he can be entertaining."

Zuckerberg isn't the only one to get it in the neck in the film.

The Winklevoss brothers bear the brunt of much humour

Sean Parker, the co-founder of Napster, whose 6% stake in Facebook has left him a billionaire, is played by Justin Timberlake as a latter day Iago, constantly plotting and scheming.

Having worked with him, Baloun says the idea of Parker as a Mephistophelean mastermind is ridiculous.

"He is easy to vilify because he is all over the place. [But] he is a visionary… kind of crazy."

There is also a less than flattering picture of Tyler and Cameron Winklevoss, the students who tried to get Zuckerberg to work on their website the HarvardConnection and who went on to row in the Olympics.

The only person portrayed in a constantly positive light is Eduardo Saverin, Zuckerberg's friend and co-founder of Facebook.

Saverin, who co-operated with Ben Mezrich on The Accidental Billionaires, the book on which The Social Network is based, comes off as an almost angelic figure in the film, a moral compass in the maelstrom.

But does a biopic like The Social Network have any obligation to stick to reality?

"Hollywood and film-makers in general when they are doing biopics have a duty to the truth," says Dennis Bingham, author of Whose Lives Are They Anyway?: The Biopic as Contemporary Film Genre. "There are films that go over the line and distort the truth."

For the subjects, there is a danger that the fictional character can take over, says Bingham.

"The film in the public memory does supplant the real person."

One such an example is Patton. George C Scott's portrayal of General George S Patton as an irascible egotist, prone to bullying, won an Oscar and created an iconic character.

Patton, of course, wasn't around to set the record straight, whereas Zuckerberg is. Some commentators have suggested the billionaire's recent $100m educational donation on the Oprah show may have been the start of a PR makeover.

Bill Gates' image is now dominated as much by his charitable work as anything else. Nobody thinks of him the way he appeared in the film Pirates of Silicon Valley.

"Anthony Michael Hall played Gates as a little brat, which was how most people saw him at that time," says Bingham.

Perhaps the strangest thing about The Social Network is that it has got nothing to do with Facebook as a phenomenon.

Jesse Eisenberg's performance has already won praise

As Sorkin, a noted internet sceptic, has confessed in New York magazine, external he could just as easily have made a movie about the making of toasters.

"He holds Zuckerberg, Facebook and the internet in contempt," says Jarvis.

Those looking for a rumination on social networking and our journey towards a more connected world will have to keep looking.

"Neither Fincher or Sorkin seem that interested in Facebook," says Kirkpatrick. "They use the growth and the money as background phenomena. They don't begin to understand it's social political and zeitgeist role."

Instead, it's the story of a personal struggle of someone who was brilliant, Kirkpatrick insists.

"For all of his geekiness he had a far better understanding of the social dynamics of college and elsewhere than most people."