Hateful protests try American commitment to free speech

- Published

The substance of the message is not supposed to matter under a free speech doctrine

When the US Supreme Court sat this week to hear a privacy case about the right to protest at a private military funeral - to scream hateful, slogans and bear signs saying "Thank God for dead soldiers" - it was an opportunity to show the earnest commitment most Americans have to free speech values more than two centuries after the Bill of Rights came into existence.

In few other democracies in the world, let alone other nation states, would a meaningful conversation about the legal protection of such vile communication have taken place on such a high level and with so much at stake.

Most countries would long ago have outlawed or limited such odious displays of publicity seeking, or at least enabled and encouraged the victims of such cynical protests to use the courts of law to punish the perpetrators.

Can you see eternally tolerant Canadians tolerating similar nasty picketing at the funerals of their fallen soldiers? Can you see it happening in Great Britain? Neither can I.

Tolerating insensitive ideas

But America generally endures even deliberately cruel expression. Not only endures it but gives it a vast protective berth under the auspices of the First Amendment to the Constitution, external.

By design and execution, and like it or not, even the most repugnant ideas, offered for the worst reasons, are not supposed to be killed in their cribs by judges but are instead to be duly vetted in the public marketplace of ideas.

That's why no one seriously suggested during the whole long case, now known to the world as Snyder v Phelps, external, that the hateful speech at issue be criminalised, restrained prior to communication or, Heaven forbid, judged on its merits.

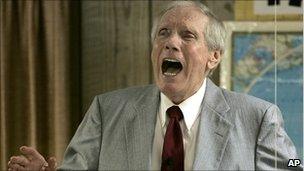

Indeed, one of the striking components of the oral argument in court was its complete lack of attention to the content of the protests - such as placards reading "God Hates Fags" - supported by Fred Phelps.

Mr Snyder's son, Marine Lance Cpl Matthew Snyder, died while serving in Iraq in 2006

Mr Phelps picketed with individuals holding such signs on the day and at the time that Albert Snyder had to bury his slain-in-battle son, Marine Lance Cpl Matthew Snyder.

Invasion of privacy

The content, timing and location of Mr Phelps' speech, a Maryland jury found in 2007, intentionally inflicted $11m (£7m) worth of emotional distress upon Mr Snyder.

Mr Phelps' conduct invaded Mr Snyder's right to privacy, jurors determined - the poor man's basic human right to bury his son in peace and quiet.

But the Supreme Court for an hour barely uttered a peep about the jury's verdict, which was subsequently overturned by a lower federal court.

And the justices had even less to say about the substance of the message Mr Phelps and his Westboro Baptist Church minions from the US state of Kansas were trying to communicate to America on what was surely one of the worst days of Albert Snyder's life.

Short of presenting a clear and present danger to national security, the substance of the message is not supposed to matter under a free speech doctrine.

The most venal speech often needs, and receives, the most protection from the justices.

Indeed, the main goal at the High Court was to determine if the justices should recognize some sort of exception for funerals, looking specifically at whether Mr Phelps' anti-gay, anti-military, anti-America speech is protected under the First Amendment.

During the oral argument, the justices effectively said to Mr Snyder that he had been wronged. But the justices also conveyed the message that the First Amendment places upon Mr Snyder a burden to convince them, even in these grim circumstances, that he warrants that particular remedy.

And the court effectively said to Mr Phelps that he may have done wrong. But the First Amendment precedent generally protects him from the sort of official punishment reflected in a jury's verdict.

Impossible to predict

Few want to deny Fred Phelps his right to speak out, however hateful his message

Despite an outpouring of national sympathy for the Snyder family and despite near universal abhorrence at the methods the Phelps family employs to disseminate its views, few commentators publicly blamed the nine justices for approaching such a gut-busting case from a starting point so heavily advantageous to the church.

Many media outlets, in fact, formally supported Mr Phelps' right to engage in such speech.

In the wake of the argument, some commentators even wondered why the Supreme Court had even decided to interject itself in such a lopsided dispute in the first place.

"The Snyder's pain is the kind of pain free speech requires us to bear," wrote American legal scholar Garrett Epps, external.

It is virtually impossible to predict how the Supreme Court will resolve Snyder v Phelps. That decision is several months away.

But in many ways America itself already has reacted to the Phelps' family's cynical strategy of interjecting itself for publicity's sake into private moments of grief.

And even the reaction is a testament to America's foundational commitment to free speech.

Forty-eight states now have passed laws reasonably limiting funeral protests to a certain time, place and manner - restricting, but not prohibiting the cruel act.

Based upon the tone and tenor of the oral argument in Snyder v Phelps, those funeral protest laws appear safe for now from constitutional challenge.

They may not help Mr Snyder in his quest for damages against Mr Phelps.

But they will back Mr Phelps off a bit the next time he and his church members seek to picket a funeral. And that's a compromise most Americans are willing to accept.

Thanks to a durable commitment to protecting even the most unpopular speech, few want to deny Fred Phelps his right to speak out so harshly against innocent people in their most anguished and vulnerable moments.

But even fewer, apparently, want to hear what he has to say.

Andrew Cohen is the legal affairs columnist for Politics Daily and Senior Legal Analyst for CBS News Radio.

- Published6 October 2010