Canada recalls Quebec separatist violence 40 years on

- Published

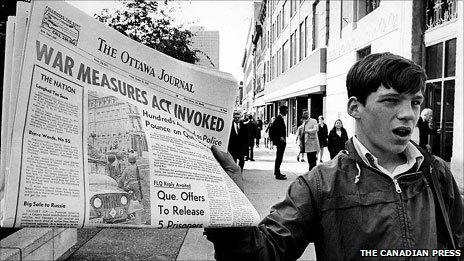

The October Crisis was a tumultuous time in Canada's history

Forty years ago, Canadians were gripped by the dramatic events surrounding the political kidnappings of a British diplomat and a Quebec politician by home-grown terrorists known as the Front de liberation du Quebec (FLQ).

The FLQ or the Quebec Liberation Front was founded in 1963 with the aim of achieving independence for Quebec, Canada's majority French-speaking province - through terrorist means, if necessary.

It emerged against the backdrop of the Cuban Revolution, US student activism against the Vietnam War and Algeria's War of Independence.

The FLQ claimed to be fighting against "a capitalist system, which they characterised as English-dominated, foreign-owned - the FLQ seemingly wanted to smash that system", Canadian War Museum historian Andrew Burtch says.

"It was a period of great political tumult," Mr Burtch adds.

Throughout the 1960s, the organisation carried out a campaign of bank and armoury raids as well as mailbox bombings in English-speaking neighbourhoods in the Montreal area, performing 200 acts in all.

Twenty-seven people were injured during the bombing of the Montreal Stock Exchange, a security guard was killed during a raid on an armoury and a bomb disposal expert lost an arm and suffered brain damage handling an explosive.

By October 1970, the FLQ had raised the stakes.

Gunmen seized James Cross, the British Trade Commissioner, from his Montreal home - sparking off a manhunt.

The diplomat, now nearly 90, is still clearly upset by the experience.

"I was under a sentence of death for 59 days, which was extremely stressful," he recently told the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC).

Among the FLQ's demands for Mr Cross's release were the freeing of jailed FLQ members, whom they called political prisoners, and the broadcasting of the FLQ manifesto, which asked the people of Quebec to join its cause.

While the document was read on the CBC, the terrorists' demands were largely unmet.

The diplomat remained at the mercy of his kidnappers.

'People shocked'

Two days later, Quebec's Vice-Premier and Minister of Labour Pierre Laporte was also kidnapped.

The Right Honourable Herb Gray was a young cabinet minister in the government of Pierre Trudeau, a popular, Quebec-born Liberal Prime Minister.

He remembers the reaction of Canadians to the news of the Laporte abduction.

"People were shocked. People felt this was something one didn't expect in Canada," Mr Gray said.

Security was ramped up in Quebec to protect prominent individuals and sites.

And in Ottawa, soldiers were deployed to protect ministers, diplomats and government buildings, like the Canadian Parliament.

Canadians were bemused by the sudden military presence on their streets.

"We had soldiers outside our door. It upset the neighbours, who were mostly elderly," Mr Gray said.

Meanwhile, the prime minister was losing patience with the FLQ.

When asked by a reporter how far he would go to maintain law and order, Mr Trudeau famously said: "Just watch me."

Two days later, a 3,000-strong pro-FLQ rally full of students, trade union officials and intellectuals took place in Montreal.

The next day, on 16 October, the Canadian government declared that Quebec was in a state of "apprehended insurrection" and invoked the War Measures Act, its first such action during peacetime.

The act allows the government to assume emergency powers in the event of war, invasion or insurrection.

The FLQ was banned, and over 1,000 troops from across Canada were called in to support the police manhunt in Quebec.

In just a few days, more than 450 people were arrested without charge and detained - though most were soon released.

Mr Trudeau explained his actions in a televised statement.

"Violent and fanatical men are attempting to destroy the unity and the freedom of Canada," he said, adding that he would not tolerate "intimidation and terror".

FLQ support fades

But it was too late for Pierre Laporte, who was found strangled the next day in the trunk of a car. The FLQ claimed responsibility - and was roundly condemned.

Rene Levesque, the leader of the separatist Parti Quebecois described the killers as "inhuman", while Herb Gray recalls the shock felt throughout Canadian society.

"We asked ourselves, 'What's going on?'" Mr Gray says.

.jpg)

James Cross was held captive for 60 days by the FLQ

Anne Trepanier, a Quebec Studies specialist at Carleton University in Ottawa said the death "completely eroded support" in Quebec for the FLQ.

Meanwhile, Mr Trudeau came under severe criticism from his political foes. The Parti Quebecois leader accused Mr Trudeau of "a panicky and altogether excessive reaction", while the leader of Canada's third party, the left-leaning New Democratic Party (NDP), accused Prime Minister Trudeau of using "a sledgehammer to crack a peanut".

But the public seemed to approve overwhelmingly of the tough approach.

Claude Belanger, a Quebec historian at Marianopolis College in Montreal, says that several polls at the time showed about 90% of Canadians - including those in Quebec - backed the measures.

"Canadians, Quebecers did not approve of the use of terrorism and kidnappings - even less when Pierre Laporte was murdered," Mr Belanger says.

By December, the crisis was, in effect, over.

James Cross was released in exchange for Cuban exile for his kidnappers - led by Jacques Lanctot. They eventually returned to Canada, and served short prison sentences.

Pierre Laporte's killers, led by Paul Rose, were found by police.

Rose and a fellow FLQ member were convicted of kidnapping and murder charges, with another member convicted of just kidnapping charges.

All were out of prison by the early 1980s. Now, all play roles in Quebec society as writers, film-makers and commentators.

Rose even worked as a politician for some time.

Revising history

Some FLQ members have sought to revise this provocative chapter in Canadian history.

Mr Lanctot said he and his accomplices never planned to kill James Cross - and the diplomat knew it.

"It was clear that we would never kill him. We told him we wouldn't hurt a fly," he recently told Radio-Canada, Canada's French-language public service broadcaster.

Mr Cross is sceptical and says he continues to feel "hate" for his former captors.

"I am sure they said the same thing to Pierre Laporte," he told the CBC.

Jean Laporte, who lost his father when he was just 11 years old, says he still suffers.

Since the crisis, separatists have sought, and failed, to achieve independence through two referenda - narrowly losing in the last one held in 1995.

The appetite for an independent Quebec now seems on the wane.

Some 60% of Quebec residents feel the issue has been settled, according to a recent poll, while former separatist leader Lucien Bouchard recently admitted that independence was unachievable.