Iran and Saudi Arabia bid for seat on UN gender agency

- Published

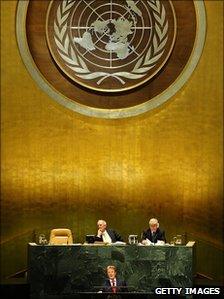

Ms Ashtiani's case has sparked an international outcry

Iran and Saudi Arabia may get seats on the board of a new UN super-agency to promote women's rights, prompting outrage from human rights and women's activists.

"We think it sends a horrible signal to women around the world who are looking with hope to the agency," said Philippe Bolopion of Human Rights Watch. "Given the abysmal record the two countries have on women's rights, their candidacy will be seen as a provocation by women around the world."

The agency is known as UN Women. After four years of delays and difficult negotiations, it was approved by the General Assembly in July and is meant to begin work in January.

It brings together four existing UN bodies into a single high-powered entity. Its aim is to increase the focus on and funding for women's issues and, through its head, Chile's former president, Michelle Bachelet, raise their profile within the United Nations.

So the vote for the 41 member executive board, set for 10 November, is a key step.

Discrimination in law

Saudi Arabia is running uncontested for one of two slots allocated to emerging donor nations. Iran's name has been put forward by the Asian group as part of a 10-nation slate, which is facing unexpected competition from a candidate that entered the race last week.

Activists acknowledge that other countries on the list also have poor track records on human rights, but say these two in particular systematically discriminate against women through their legal systems.

In Saudi Arabia women are forbidden to drive, and cannot take significant decisions without the permission of a male relative.

Ban Ki-moon has said Ms Bachelet would bring global leadership to the job

And Iran drew international condemnation recently, when it was reported that a woman had been sentenced to death by stoning after being convicted of adultery and complicity in her husband's murder. The sentence has reportedly been changed to hanging, but she is now the focus of an international campaign to save her from execution.

It is not clear what impact a country's human rights record will have on the board, or exactly what influence the board itself will have.

Organisers have tried to keep the mandate as technical as possible, modelling it on those used by other UN development funds and programmes.

But issues related to women are deeply politicised at the UN. There could be fights over budget allocations and programme priorities not seen in other agencies. There is also a fear the board could get mired in debates over fundamental principles rather than surging ahead with empowering women in all spheres.

'Constructive and objective partner'

"To have actors that could open up debates on whether women have equality in law and practice, or on whether women's rights are human rights, will take away from precious time the UN has to address monumental issues that affect women and girls," said Taina Bien-Aime, the executive director of a gender rights group, Equality Now.

"As an outsider our fear is that those debates would happen with actors like Saudi Arabia and Iran."

But would they?

Negotiations over the establishment of UN Women took four years

Diplomatic sources say Saudi Arabia almost never sits on the boards of UN agencies, so it is difficult to predict from past behaviour what it would do now.

On the other hand, they say, Iran is on the boards of many funds and programmes, including the one that oversees the UN's Development Agency (UNDP) and UN Population Fund (UNFPA). And on that, it has been a "constructive and objective partner" with no agenda.

The BBC approached both missions for comment but neither had responded by the time of publication.

There are also signs some Western countries may be pursuing agendas of their own. Usually for an agency like this, a mission's technical and development people would be involved, say diplomatic sources. However, in this case many states are sending officers who are more political and human rights oriented, suggesting a confrontational rather than consensual approach.

Those who have fought long and hard for UN Women are hoping that the board will be able to settle any political battles at the beginning of its tenure and move on quickly to the nuts and bolts of approving programmes and running audits.

Their fear is that the super-agency will become another UN forum for political battles, some of which have little to do with women's rights.

- Published12 August 2010

- Published2 June 2010