Malaria vaccine: Inside look at first human trial

- Published

Nick van Gorden explains why he volunteered to be bitten by infected mosquitoes

The first clinical trial for a vaccine against the most widespread strain of malaria, Plasmodium vivax, is now under way at the Walter Reed Army Institute for Research (WRAIR), near Washington DC. The BBC's Jane O'Brien speaks with those heading the trial and individuals who are being bitten by infected mosquitoes to help further the research.

US army medic Joseph Civitello admits that becoming deliberately infected with malaria - one of the world's deadliest diseases - is "definitely nuts".

But without such volunteers, it would be almost impossible to test a new vaccine aimed at protecting the military overseas and preventing some of the estimated 300 million cases of malaria that occur every year.

First Sgt Civitello is part of the world's first clinical trial of a vaccine against Plasmodium vivax - the most widespread strain of malaria.

It's not as deadly as Plasmodium falciparum, which is endemic in Africa and kills millions of people, but it can resurface years after infection and still make its victims extremely ill.

"It was weird because I did this knowing I was going to get sick," says Sgt Civitello.

"Fortunately I'm in a hotel room with doctors and nurses nearby and not out in the woods somewhere."

Unlike most of the other volunteers in this unique trial, Sgt Civitello wasn't given the test vaccine.

Human test subjects

He's part of a small control group - a human yardstick - needed by doctors to confirm that all the study participants have been infected.

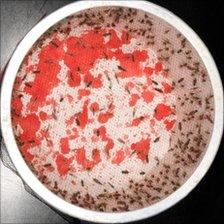

Mosquitoes infected with the Plasmodium vivax strain are fed blood

And as predicted, about 10 days after being bitten by mosquitoes in a laboratory, he displayed all the symptoms of malaria.

"It started out with a headache, then a general malaise throughout the day. My eyeballs hurt, and I was really sensitive to cold and hot - my skin was sensitive and I had sweats and chills all night long. It was like extremely bad flu," Sgt Civitello said.

Twenty-seven other volunteers in the study had been given varying doses of the vaccine for several months prior to infection.

Developed by scientists at the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research, it consists of a protein that stimulates the body's immune system and triggers its natural defences against the disease.

Then, at the beginning of November, they were bitten by mosquitoes imported from Thailand and infected with Plasmodium vivax malaria.

A small carton containing the insects was placed on their arms for several minutes and repeated until they received five bites each, making infection a certainty.

"What makes this process unique is that we don't know whether a vaccine has worked unless it is exposed to a pathogen - in this case malaria. And malaria can only be transmitted through the bite of a mosquito," says Col Christian Ockenhouse, director of the Malaria Vaccine Research Programme at WRAIR.

Volunteers are bitten by infected mosquitoes to see if the vaccine protects them from malaria

He adds: "What we do here plays a critical, pivotal role in the fight against malaria. Without this model of challenging the human body with malaria, we would be unable to effectively develop and figure out whether a vaccine works or not."

"It costs millions of dollars to test any vaccine and if we can safely eliminate vaccines that don't work and push into further trials those that do show promise, it will save millions of dollars."

Malaria vaccines have remained elusive because of the parasite's ability to rapidly evolve and adapt to its human host.

An international movement

The Gates Foundation has spent $1.4bn fighting the disease and the global campaign involves many organisations from WRAIR to big pharmaceutical companies, such as GlaxoSmithKline.

The US military has been at the forefront of developing vaccines ever since the Civil War because of malaria's ability to disrupt operations if soldiers get sick. The Plasmodium vivax strain is a particular problem for troops serving in Afghanistan.

At the moment, the only other way to prevent infection is to avoid mosquito bites by using bed nets or insecticides.

But a trial for a Plasmodium falciparum malaria vaccine, involving 16,000 children in Africa, could be completed next year.

Volunteers in the world's first Plasmodium vivax malaria vaccine trial are given several thousand dollars in compensation.

They say the money is an incentive, but most take part because they want to further medical science.

"My dad was a doctor, and I always knew that in order to advance the medical field you need human subjects," says Mengee Shan, a volunteer in the control group.

"And being a science major myself, I felt I would have to rethink my career if I couldn't dedicate myself to doing something like this, especially if I am going to ask others to take part in my medical projects."

Renee Kruger, a single mother from Maryland, says the cash will help pay for Christmas but feels she's doing something worthwhile.

"Some people may be scared of doing this, but every drug or over-the-counter medicine needed to be tested on a human, so that's why I'm doing it."

Twelve days after being bitten, she exhibits no signs of infection, but other vaccine testers are showing positive for malaria.

Pending results

Scientists say it'll be another week before they can determine full extent of the trial's success or failure.

The vaccine may have offered limited protection to some of the volunteers or be completely effective in others.

Volunteers in the Plasmodium vivax malaria vaccine trial are paid several thousand dollars each

In any event, the results will be used to develop better vaccines in the future.

"It typically takes 15 to 20 years to develop a new drug or vaccine that goes to market," says Col Ockenhouse.

"But the world doesn't have 15 or 20 years to wait for another malaria vaccine - so anything we can do to rapidly progress this development process is most important."

Meanwhile, the volunteers are staying at a hotel in Maryland, where they can be monitored around the clock.

Some of the rooms have been converted into a clinic and laboratory so that blood samples can be tested immediately for any signs of malaria.

If the volunteers do succumb they are instantly treated with drugs to ensure there will be no lasting consequences of the trial.

- Published29 October 2010

- Published29 October 2010