What happens when your unemployment benefits stop?

- Published

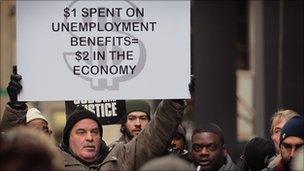

99ers want unemployment benefits to be paid out beyond 99 weeks

In the United States, benefits for the long-term unemployed can be claimed for a maximum of 99 weeks. But what happens to those who don't find a job in that time, and find their payments have stopped coming in?

"I thought I'd be back on my feet before I could blink my eyes," muses Theresa Iacovo, who has been out of work since September 2008.

The 49-year-old, who lost her job at the start of the economic downturn is one of the so-called 99ers - who get their name from the fact they have claimed 99 weeks of payments but are still unable to find a job.

In the US unemployment benefit can generally only be claimed for 26 weeks, but since the economic downturn, congress has extended this period. Amid bitter political debate, an extension to the benefits now hangs in the balance as part of a tentative deal struck to extend soon-to-expire tax cuts, external.

But the current 99 weeks hasn't been long enough for Theresa, who has failed to secure work, despite having sent her curriculum vitae to more than 2,500 companies.

Work incentive?

Theresa Iacovo cannot afford to pay for her late father's headstone

Many will say that it must be possible to find some kind of work in two years, and that getting benefits is an excuse to avoid having to work.

But for Theresa the reality is very different. She has only had one interview in almost two years, despite trying for jobs as a receptionist, waitress and salesperson.

"If there were jobs out there we would have them," she says.

To those that say she has had long enough on benefits she responds: "I agree that 99 weeks is long enough for anyone to suffer and to sacrifice. No-one chooses to lives with less, no-one aspires to become poor."

The amount paid out in unemployment benefits can vary from state to state, but averages $302.90 (£192.70) a week. Until August of this year Theresa, who is single, was claiming $389 (£248) a week.

But for her, that wasn't enough to live on. She had to give up the waterfront apartment she once rented in Long Island and, to her deep regret, wasn't able to afford to pay for a headstone on her father's grave when he died.

Now she has no income at all. She stays with a friend in New York and goes to food pantries to eat.

Theresa is one of an estimated five million Americans who have exhausted all their unemployment payments, and are no longer supported by any welfare.

A black hole?

In a buoyant economy withdrawing benefits from claimants can force people to go out and get a job argues Heidi Shierholz, an economist at the Economic Policy Institute. But in current circumstances, it is a different story, she argues.

"We can kick people off and it will certainly make people more desperate to find a job. But in a labour market like this it's not going to make them more likely to find a job because the jobs aren't there."

With the unemployment rate at 9.8%, Ms Shierholz shares the view some campaign groups hold - that benefits should be extended past 99 weeks.

99er support groups argue that otherwise, people are being left in a black hole.

"These benefits are money we'll plough back into the economy... it's going to be good for the economy if we get it," argues Joe Stanick, a degree-educated engineer from New Jersey, and a 99er, who has been out of work for two years. He lost his job in the housing sector and has struggled to secure any kind of job since.

"We're people who want to work," he says. "We want to get back to our normal lives and become productive tax-paying citizens."

Mr Stanick is currently living off savings, which he says are now down to the last few hundred dollars. He says he is often told he is over-qualified when he applies for service jobs, such as working in fast food chains.

He is 57 and says many of his fellow 99ers who are struggling to get work fit into this age bracket. "I feel there's a certain amount of age discrimination. It's harder to re-enter the work force when you're 57 and competing with someone who is 27."

Safety net

With cuts being made in many areas of government, the Republican Party in the US had been calling for benefit payments to revert to the 26-week period. If the deal with President Obama's Democrats is ratified, the 99-week extension will continue for at least another 13 months.

Joe Stanick has been out of work for two years

But David Keating, executive director for The Club for Growth, an organisation which believes in lower taxes, argues that while the US has other safety net programmes like food stamps, "you don't want to have an unemployment programme that provides a stipend forever".

"Part of the problem is that by taking on more and more spending, the government is making it more difficult for people to create jobs. It's making it more difficult for businesses to hire people," he believes.

Mr Keating argues people should take out their own unemployment insurance, to prepare for the worst case scenario. "People can buy insurance for all kinds of things, there's no reason why they can't buy their own unemployment insurance," he adds.

But for Theresa it's too late for that. Like the rest of the 99ers, any hope of a secure future is linked to finding a job.

"I live on a strong diet of hope because if I give up hope there's no reason to get out of bed in the morning," she says.

"I continue to believe that America will not forget about its people, and that one resume will finally hit the desk of the person who actually wants to hire me."