Mexico's drug war: Made in the US

- Published

Mexican drug cartels are reportedly acquiring most of their weapons from the US

The Obama administration has called Mexican drug cartels "the single greatest organised crime threat to America". But why are the cartels fighting each other with American guns?

Jim Pruett still has the boulder that suspected weapons traffickers dumped through the glass front of his Houston gun store last month.

The night-time robbery, which took only a matter of minutes, resulted in the loss of 12 Glock handguns and six military-style AR-15 assault rifles.

With a combined retail value of $12,540 (£8,020), these weapons are highly prized by drug cartels in Mexico, where legal gun sales are tightly and centrally controlled.

"They knew exactly what they were looking for," Mr Pruett says.

"It was probably a robbery to order - not necessarily an order by the head guys of the cartel, but by lower echelon people working for them," he adds.

The 66-year-old Vietnam veteran explains that he has since added steel bars to his store front, together with hi-tech glass that can withstand the impact of a car bomb.

Gunshop owner Jim Pruett was recently robbed: 'We are at war with the cartels'

"But the ultimate solution is for me to stay here at night with one of our AR-15s," Mr Pruett says.

"The next time they come through that door we'll be ready."

'Straw purchasers'

It should not come to that, for a very good reason - Mexican drug cartels generally have no need to rob guns. It is far easier to acquire them legally.

They do it by using so-called "straw purchasers", individuals with clean criminal records who will comfortably pass the strict FBI background checks required of licensed firearms dealers.

Typically, straw purchasers are American citizens and green card holders in need of a little extra cash.

"What I would tend to look for would be young females buying high-powered rifles," explains a Houston-based special agent with the Bureau of Alcohol Tobacco and Firearms (ATF).

For operational reasons, the ATF asked the BBC to withhold the name of the agent, whose task is to detect straw purchases at the city's more than 300 gun stores.

On the road in Houston with an ATF special agent

"We had a case of a single mum with two kids," he says.

"She was behind on her rent, and a guy offered her $100 (£63) per gun - so she went and bought three guns and made $300 in fifteen minutes."

The woman escaped prosecution, after assisting agents investigating a wider trafficking network.

Tracing weapons

Since President Felipe Calderon took office in 2006, more than 30,000 people have died in drug-related violence in Mexico, the government says.

In the same time, Mexico's police and army have seized 93,000 guns from alleged drug traffickers.

In partnership with the Mexican authorities, ATF number-crunchers have sought to trace these weapons, matching recovered guns to their initial point of sale.

Most firearms seized in Mexico and traced are from the US, studies show

A 2009 report to Congress by the US Government Accountability Office reports that more than 90% of the "firearms seized in Mexico and traced over the past 3 years have come from the United States".

Of these, approximately 40% originated in Texas.

US gun lobbyists point out that only a quarter of seized weapons are submitted by the Mexican authorities to the ATF for tracing.

So there is no way of knowing precisely what proportion of the cartels' guns are American, just as there is no clue to the overall number of US guns still in use by the cartels.

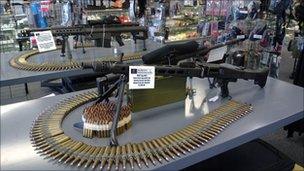

What is certain is that trafficked guns are becoming bigger and more powerful, as the cartels seek firepower equal to that of the Mexican military.

"Back in the 1990s, we were still seeing small calibre handguns and single-barrel shotguns," says the Houston-based special agent.

"But from around 2004 onwards, we saw an upswing in military-style weapons - like AK47 and AR-15 clones and high-capacity 9mm pistols."

"Whatever the Mexican military is using, the cartels want," he says.

'More ambitious approach'

Privately, investigators acknowledge the limits of existing US laws.

Currently, there is no dedicated federal statute addressing arms trafficking, while most prosecutions end in a fine or modest prison sentence for individual straw purchasers.

The Department of Justice has called for a more ambitious approach, focused higher up the cartels' chain of command.

But mindful of America's powerful gun lobby, politicians have shown little appetite for changing the law.

Another issue is money. For 2010, the ATF was allocated $55.4m (£35m) for Project Gunrunner, an ongoing operation targeting cross-border weapons smugglers.

But that amount pales into insignificance when compared with the multi-billion dollar value of the US-Mexican drugs trade.

Mexican media have estimated the cartels' annual turnover at up to $40bn.

"We could always use more resources," admits Dewey Webb, the lead Special Agent at ATF's Houston division.

But, he adds: "We've made a significant dent in cartel activity - to the point where they're now going deeper into the United States to buy their guns.

"That costs them more money, and there's a greater chance of detection."

But for Mexican drug barons, whose business-savvy ways have been likened to those of Fortune 500 executives, weapons smuggling is an easy economy of scale.

In trafficking drugs north to the US, cartels already have routes, resources and manpower in place.

Using the same infrastructure to traffic weapons to the south is a logical variant of the business model.

At a bridge marking the frontier between El Paso in Texas and Ciudad Juarez in Mexico, drivers on the Mexican side sometimes wait for hours to have their vehicles searched for drugs by US officials.

But the reverse journey is remarkably straightforward.

Most drivers are waved through untroubled - only occasionally are southbound vehicles stopped.

One can only guess how many US guns are crossing the frontier undetected.