Ahmed Ghailani sentence: The future of Guantanamo

- Published

Ahmed Ghailani was cleared of more than 200 charges but convicted on one conspiracy count

The first Guantanamo Bay detainee to be tried in a civilian court has been sentenced to life in prison. The BBC's Laura Trevelyan in New York looks at how the trial of Ahmed Ghailani has complicated the Obama administration's strategy of trying Guantanamo inmates in federal courts.

Ahmed Ghailani was convicted on just one charge relating to the 1998 bombings of two US embassies in East Africa - conspiracy to damage or destroy US property with explosives.

He was cleared of more than 200 others, including intent to kill.

Republican Congressman Peter King, from Long Island just outside New York City, said afterwards: "This tragic verdict demonstrates the absolute insanity of the Obama administration's decision to try al-Qaeda terrorists in civilian courts."

While the conviction was not the resounding one the US Department of Justice would have liked, US Attorney General Eric Holder seized on Ghailani's life imprisonment to press the case for civilian trials.

"A life term imposed on a Tanzanian national for his role in the bombings of two US embassies proves the strength of American courts in trying terror cases," he said.

'Committed'

But it is hard to envision when the next civilian trial of a Guantanamo detainee will be, or indeed when President Barack Obama can close the Guantanamo Bay military prison, as he promised in his first days in office.

The Obama administration says it is committed to closing the Guantanamo Bay detention centre

US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton reiterated on Tuesday that the US is "absolutely committed" to closing the controversial facility. But how?

In the weeks following the Ghailani verdict, Congress passed a law preventing military funds from being used to transfer Guantanamo inmates to the US.

This makes it in practice very difficult for the Obama administration to empty the detention centre, and to move detainees and try them in civilian courts in the US.

Professor Jonathan Hafetz of Seton Hall Law School in New Jersey, who represents a Guantanamo detainee, said it would have been much harder for Congress to pass such a law if Ghailani had been convicted on all counts.

"The Ghailani verdict provided ammunition for lawmakers and groups opposed to the use of civilian courts to thwart the future use of the federal justice system," he said.

Trial critics

Ghailani was subject to what the government calls "enhanced interrogation" by the CIA at a secret prison, and any evidence prosecutors presented that had been obtained during that process risked being declared inadmissible in court.

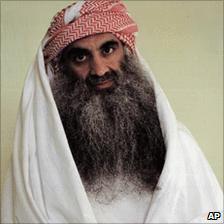

The White House may have to abandon plans to try Mr Mohammed

Indeed, US prosecutors suffered an early setback when Judge Lewis Kaplan barred a key government witness from testifying, ruling he had been named by Ghailani while "under duress".

Therein lies the problem, critics of civilian trials say. They argue acts of war should not be treated as law enforcement issues.

One of Ghailani's lawyers, Michael Bachrach, took the opposite view, telling the BBC the trial showed the jury was able to weigh evidence without undue influence from the politics of the case.

"The fact that Mr Ghailani was able to receive a fair trial shows the system worked," he said.

As a presidential candidate, Mr Obama criticised as "flawed" the military commissions the Bush administration established to try Guantanamo detainees, but he may now have to revive them.

Given the barrier Congress has erected to moving detainees from Guantanamo, if the US government wants to try the inmates, for the moment the only practical option seems to be the military commissions.

Indefinite detention

The New York Times has reported, external that Abd al-Rahim al-Nashiri, a Saudi accused of planning the 2000 bombing of the American destroyer Cole in Yemen, could be one of the first to be charged and then tried.

Others like Mohamedou Slahi, a Mauritanian represented by Mr Hafetz, face the prospect of indefinite detention without trial at Guantanamo.

Mr Slahi was originally arrested in 2001, soon after the 9/11 attacks, and accused of involvement in a series of attempted attacks in the US around the turn of the millennium.

Those charges have since been dropped, and he is now being held because of his alleged connections with al-Qaeda.

Mr Slahi and others were designated "enemy combatants" by the Bush administration, but they have now been renamed "unprivileged belligerents" and remain at Guantanamo.

Ghailani has learned his fate and is preparing for a life spent behind bars. The Obama administration once hoped to try Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, the alleged mastermind of the 9/11 attacks, in a federal court in New York. When that might happen is anyone's guess.

- Published25 January 2011

- Published9 December 2010

- Published6 October 2010

- Published18 November 2010

- Published18 November 2010