What does 'government shutdown' mean?

- Published

The 30 September deadline is the second shutdown threat of 2011

Since Republicans won control of the House of Representatives in 2010, financing the federal government has become one of the most contentious issues in Congress.

In April, a bitterly divided Congress reached an 11th hour deal to keep the government open for the rest of the fiscal year - until 1 October, the deadline to pass the 2012 budget.

That continuing resolution (CR) included $38bn (£24bn) in cuts from the existing 2010 budget, partially satisfying calls for deeper cuts from Tea Party-backed members.

With no 2012 budget in place, Congress is now hoping to pass a CR by 30 September to avoid a shutdown.

However, a lesser version of the partisan rancour that led up to April's near-shutdown has pushed Congress back against its deadline for the second time in one year.

This time, Democrats and Republicans are arguing over the level of funding for aid to victims of natural disasters, and whether or not additional cuts should be made in the budget to pay for it.

In between the two shutdown deadlines, congressional Republicans refused to raise the US debt ceiling limit without further, long-term cuts to the federal budget.

The debate over the debt ceiling was highly partisan and ended in another last-minute compromise, with Congress creating a 'supercommittee', tasked with reducing the deficit by more than $1tn dollars over 10 years.

For Democrats, the last government shutdowns - led by congressional Republicans during the Clinton years - worked out quite well.

Republicans were mostly blamed for the negative effects of the shutdown, and were portrayed as selfish and petty.

Many commentators credit the 1995 and 1996 shutdowns with helping President Bill Clinton coast to an easy victory in the 1996 presidential election.

Although the term "shutdown" is dramatic, the government in fact mostly continues to function during a shutdown.

No passports

Government shutdowns are not uncommon. Although there hasn't been one since 1995, the US government shut down 10 times during the Carter and Reagan administrations.

Government shutdowns during the Clinton era may have helped his re-election

Shutdowns happen because a law passed in 1870 prohibits the government from operating if a budget hasn't been passed, except in the case of emergencies.

That law has been interpreted to exempt so-called essential services, including national security, air traffic control, inpatient medical services, emergency outpatient medicine, disaster assistance, prisons, borrowing and taxation, and electricity production.

US military operations in Iraq, Afghanistan and Libya will not be affected.

Congress and the president are also exempt because their funding is constitutionally mandated.

So what is affected?

The Congressional Research Service found, external that during the Clinton-era shutdowns - which lasted 26 days - veterans' services all but ceased, the National Park Service shuttered 368 sites, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention stopped disease monitoring and toxic waste clean-up was suspended.

Over 30,000 applications for US visas were stalled each day and 200,000 passport applications sat unattended on desks.

Like all other departments, the state department will have to determine which of the services it provides in foreign embassies are "essential", but they would probably shut down or operate on skeleton staffing.

Customs and immigration at US airports and borders, however, would continue to function.

In previous shutdowns, no new patients were enrolled in clinical research trials at the National Institute of Health, and its disease hotline went unanswered.

Alcohol, tobacco and firearms applications were affected, as were border patrol and law enforcement recruitment, delinquent child support case management and all of the national monuments in Washington DC.

Social security cheques were posted, but administrators were unable to handle queries about address changes, lost cheques, new enrolees and the like.

Money for nothing

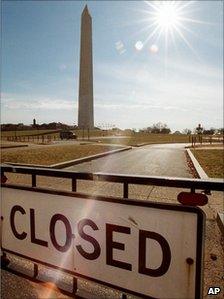

The Washington Monument was closed to tourists in the 1996 shutdown

If a shutdown happens now, government workers are likely to have to shut off their Blackberries. Answering work emails is in contravention of the 1870 act which prohibits the government from receiving free labour.

Employees who try to sneak in some free work could land themselves a $5,000 (£3,118) fine or two years in prison.

Mostly a government shutdown works by furloughing non-essential government workers.

They are usually suspended without pay and later given back pay, even though they had not worked during that period.

That helps contribute to the irony: shutting down the government is expensive.

Fines and fees aren't collected, the tourism industry suffers from the closure of national parks and employees are ultimately paid for not doing any work.

The flow-on effects in the economy are hard to quantify.

But some estimates put the cost of government shutdowns in 1995 and 1996 at over $1.25bn - much of it due to inefficiency.

- Published17 March 2011

- Published2 March 2011

- Published19 February 2011

- Published14 February 2011