Japan quake: Nuclear lessons from Three Mile Island

- Published

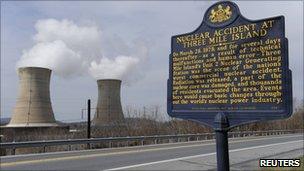

The plant still operates, although the affected unit has been mothballed since the accident

Three decades before the current nuclear crisis in Japan, the eyes of the world were on an unfolding disaster at America's Three Mile Island nuclear plant.

"The world has never known a day quite like today. It faced the considerable uncertainties and dangers of the worst nuclear power plant accident of the atomic age," newsman Walter Cronkite intoned on the CBS evening news, two nights after the disaster at the Three Mile Island nuclear plant began.

"The horror tonight is that it could get much worse. It is not an atomic explosion that is feared. The experts say that is impossible. But the spectre was raised of perhaps the next most serious kind of nuclear catastrophe - a massive release of radioactivity."

Fortunately that did not happen, but such was the atmosphere of fear and uncertainty surrounding a nuclear accident that ultimately resulted in comparatively minimal damage.

Still, it remains America's worst commercial nuclear accident.

Human error

The event that became seared into America's collective memory began at 4am on Wednesday 28 March, 1979.

A relatively routine malfunction in a non-nuclear system at the Three Mile Island (TMI) plant near Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, in America's northeast, caused a relief valve to open, releasing coolant from the core.

The valve should have closed after a moment, but it didn't, and a large volume of coolant escaped.

There was no straightforward way for the plant's operators to know that the valve was the problem. No instrument on their control panel indicated whether it was open or closed.

A sign alerts visitors to the near disaster at Three Mile Island

Operators knew something was going wrong, though - alarms sounded and lights were flashing.

They mistakenly diagnosed the issue as being too much coolant in the pressuriser and shut off the emergency core cooling system, the first in a series of missteps that escalated the crisis.

"In not knowing what was going wrong and taking exactly the wrong action, they exacerbated the problem by orders of magnitude," says J Samuel Walker, a historian who worked for many years for the Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC), the US atomic agency and nuclear watchdog.

Operators worked furiously for days to minimize the meltdown.

It wasn't until 1985, when sophisticated cameras were sent into the core, that authorities understood the enormous extent of the meltdown.

The TMI disaster took over 12 years to clean up, at a cost of about $973m (£605m).

Fortunately, little radiation was released, and multiple studies have shown no serious health impacts.

There was no documented increase in cancers. Links between TMI and problems with livestock in the area, including deaths and reproductive issues, have not been proven.

But, even though the TMI accident didn't end in a nuclear catastrophe, it is still a uniquely terrifying chapter in American history.

Mixed messages

The entire country held its breath; nightly news broadcasts devoted entire shows to TMI. It was truly a moment of national crisis.

The climate of anxiety stemmed in large part from mixed messages, misinformation, and a cultural context that included doomsday films like The China Syndrome and anti-nuclear protesters seeding fears of disaster.

According to Mr Walker, Metropolitan Edison, the company which operated the plant, initially sought to downplay concerns, partly because even they didn't have a full understanding of the problem.

The understated equivocations of their spokesmen - and their genuine uncertainty about the situation - engendered mistrust, particularly among those in the vicinity. Media coverage citing concerned nuclear experts served to heighten fears.

Soon, misinformation about a hydrogen bubble, which had formed in the containment vessel after zirconium-clad fuel rods were exposed, turned into full-blown and mostly unfounded anxiety about an atomic explosion

Pennsylvania Governor Richard Thornburgh responsibly urged pregnant women and children under five to evacuate the surrounding areas.

His warning was advisory in nature - a measure of caution, even though no increased radiation levels had been detected offsite - but still raised concerns and an estimated 75,000 people evacuated.

"Nobody could say for certain that the plant was under control. People in the area, with good reason, were very concerned. Each family had to make the decision as to whether to evacuate voluntarily," said Mr Walker.

"People were making all kinds of excruciating personal decisions with no way of knowing what the right decisions were."

On Sunday, the fifth day of the disaster, President Jimmy Carter travelled to TMI to allay the public's fears, reassuring America and the world that everything that could be done was being done.

But he was photographed wearing yellow protective booties over his shoes to guard against radiation, which further distressed many Americans.

Legacy of TMI

TMI ended up mostly being a disaster averted, not really comparable to the tragedy of Chernobyl several years later.

But it did have a lasting impact on nuclear policy, both in the US and abroad.

A presidential commission was ordered, a series of investigations were conducted, and significant changes were made to regulatory policies and processes.

Although the TMI operators couldn't have known differently when the accident happened, human error played an enormous role in worsening the crisis.

After TMI, there was a new emphasis on operator training. Changes were made to control room instrumentation, and other equipment improvements were implemented to counter the possibility of hydrogen bubbles.

Several plants with similar designs were temporarily shuttered, and the entire US nuclear power industry slowed for decades.

TMI reopened after several years and still produces electricity today, but the affected tower has been mothballed since the accident.

The TMI disaster echoed around the world, and many other countries adopted the recommendations of the presidential commission.

Mr Walker says he sees some similarities between TMI and the situation in Japan, particularly in terms of the climate of concern and the worries of both nuclear specialists and locals.

"The Japanese government and Tokyo Electric doing all they can to explain what is going on, but what they know changes from hour to hour," he said.

But in the end, the radiation released from TMI was far from catastrophic.

"Hopefully things will turn out that well and that happily in Japan but, right now, we have no way of knowing," Mr Walker said.