Will Canadian opposition parties push Harper out?

- Published

All three Canadian opposition parties have withdrawn their support for Stephen Harper's government

Canada is almost certainly headed for a federal election this spring. If so, it will pit a controversial two-term minority Conservative government, seeking a third mandate, against a divided opposition apparently determined to take Canadians to a poll few of them seem to want.

This week's withdrawal of support for Prime Minister Stephen Harper's government by all three opposition parties, ostensibly over a budget delivered on Tuesday, caps several weeks of escalating disputes.

On Monday, a report by an all-party committee of MPs found the Conservative government in "contempt of Parliament" for failing to produce documents disclosing the estimated cost of several controversial areas of expenditure, including the budget for proposed crime legislation and the purchase of F-35 fighter jets.

The main opposition Liberal Party and its leader, author and former broadcaster Michael Ignatieff, intend to make the non-disclosure issue and government ethics the focus of a no-confidence motion on Friday, which is expected officially to bring the government down.

"It's a question of respect for the principles and institutions of our democracy," Mr Ignatieff said on Wednesday.

He insisted the government had not only lost the confidence of parliament, but of the Canadian people as well.

Meanwhile, opposition support for Canada's governing Conservatives had already collapsed on Tuesday over the budget.

Harper's ultimatum

The proposed spending measures offered a mixture of deficit reduction proposals, including corporate tax cuts but also fresh spending on social programmes, intended to gain the support of the left-leaning New Democratic Party (NDP).

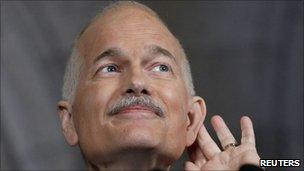

Jack Layton has led the NDP in Canada since 2003

But following a short meeting with Mr Harper, NDP leader Jack Layton emerged dissatisfied.

"I said to the Prime Minister, 'You've got a choice here - you can work with us to tackle some key issues facing Canadians right now or you can choose an election,'" said Mr Layton.

For his part, Mr Harper stoutly defended his finance minister's budget and said that he was disappointed the opposition parties were about to force what he called an "unnecessary" election.

Mr Harper painted his party as the one most dedicated to building the country's economy during a period of uncertainly.

"Our economy is not a political game," Mr Harper said to reporters on Wednesday.

"The global recovery is still fragile. Relative to other nations, Canada's economic recovery has been strong, but its continuation is by no means assured," he said, adding that "many threats remain".

Economic perseverance

Mr Harper's party leans further to the right than most conservative governments have historically done in Canada.

Michael Ignatieff is set to fight his first election at the helm of the Liberal Party

It was born out of a political merger in 2003 between two competing parties that had been splitting the vote on the right.

In power since 2006, the Harper government has won grassroots support for policies that have included middle-class tax cuts, a tougher stand on law and order and prudent stewardship of the Canadian economy.

And this support is due in part to a highly regulated banking and mortgage industry that has emerged far less economically damaged than its large trading partner, the United States.

But that populist support has consistently failed to transform Conservative fortunes into a parliamentary majority.

Polls suggest some Canadians fear the party will adopt more socially conservative policies, such as a tightening of the country's abortion laws, should it be given a stronger mandate.

Canadians have also been divided over the way that a government that came to power promising transparency and openness has often handled criticism and scandal with stonewalling and secrecy.

'Low-road operator'

Mr Harper's personal style has also become an issue.

Already long accepted as far more of a grey "policy wonk" than a classic baby-kissing politician, his iron-grip control over his party members and the messages they send out has led to much negative coverage in the Canadian media.

Lawrence Martin, a political columnist with Canada's Globe and Mail newspaper, says that Mr Harper's autocratic style is a turn-off for many Canadians.

"He's just not seen to be an honourable leader," says Mr Martin. "He's seen to be a low-road operator with very little regard for democracy."

But the Canadian media has also been somewhat bewildered by the opposition's eagerness to pull the plug on the government, given that the main opposition Liberals are trailing by as much as 10 points in opinion polls, external - and there seem to be few real reasons or burning issues driving Canadians to the polls.

Mr Martin says the person with the most to prove is Mr Ignatieff, fighting his first election at the helm of his Liberal Party.

"All the other leaders in this campaign are defined commodities, so Ignatieff is the real wild card," Mr Martin says.

The opinion polls will not make heartening reading for Mr Ignatieff, who so far seems to have had difficulty connecting with the electorate.

Conservative attack advertising questions the patriotism of the scholarly, sometimes awkward-looking former Harvard professor, who has spent much of his career away from Canada.

But those same opinion polls show the Conservatives are still tantalisingly short of getting their majority.

If an election were held tomorrow, Canadians would be right back where they began - with a hung parliament.

And as it stands, Canadians are highly likely to be going to the polls in early May, the country's fourth election in seven years.

- Published23 March 2011

- Published22 March 2011

- Published31 August 2010