Q&A: Guantanamo detentions

- Published

More than 11 years after the US government opened its detention facility at Guantanamo Bay, 166 inmates remain at the prison, many without charge, while trial by military commission of five prisoners face further delays.

And now more than 100 prisoners have reportedly joined a hunger strike.

BBC News explores the issues and politics surrounding the detention of suspects at the US facility in Cuba.

Why are many of the inmates at the Guantanamo Bay prison on a hunger strike?

In February 2013 some Guantanamo inmates started a hunger strike, in protest against their indefinite detention.

The strike has spread and by the end of April, 100 of the 166 prisoners HAD joined the strike. Twenty-one of them were being force-fed through a tube.

There have been several protests at Guantanamo, but the current hunger strike is one of the most sustained and widespread efforts.

How many terror suspects are due to be tried by military commission?

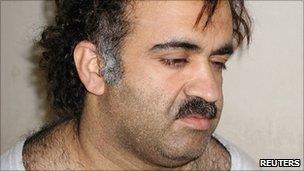

Of 166 inmates at Guantanamo Bay, five terror suspects including Khalid Sheikh Mohammed are to be tried by military tribunal.

There are still 166 detainees at Guantanamo Bay

An Obama administration interagency task force identified 36 detainees, external who are the subject of active investigations and could be tried in civil or military courts.

But because Congress has refused to fund civil trials it is unclear how many of those cases will proceed to military courts.

The task force classified 48 of the remaining detainees as being too dangerous to release but could not be taken to trial. They are being indefinitely detained.

What has happened in the Khalid Sheikh Mohammed case so far?

Alleged Mohammed and co-accused Ali Abd al-Aziz Ali, Ramzi Binalshibh, Mustafa Ahmad al-Hawsawi and Walid bin Attash appeared at pre-trial hearings in December 2008 and January 2009.

The defendants, who face charges including terrorism, hijacking and murder, have all said they do not want to be represented by US military lawyers.

At the December 2008 hearing they came face to face with relatives of those killed in the 11 September attacks.

A second round of pre-trial hearings finished in January 2013, but proceedings were disrupted after a secret government censor was discovered when courtroom sound was cut during a discussion about CIA prisons.

The judge ordered the removal of the censorship equipment, but the order could add delays to the proceedings.

As they stand, how do the current tribunals/commissions work?

The Guantanamo tribunals were originally governed the 2006 Military Commissions Act, a Bush administration law which attracted some controversy.

Khalid Sheikh Mohammed was captured in Pakistan in 2003

The act establishes different rules to try terror suspects from those which operate in regular civilian or military courts. In 2009, these rules were amended by the Obama administration and the Democratic-controlled Congress to strengthen defendants' rights.

Military commissions are made up of between five and at least 12 US armed forces officers in cases where the death penalty is sought. A qualified military judge presides over the hearing.

At least two-thirds of the commission members have to be in favour of a conviction - a departure from the unanimity required by US civil courts.

For a sentence of death, which can be sought if death occurred as a result of a defendant's action, all 12 commission members have to agree. The final decision on carrying out a death sentence is taken by the US president.

What are the safeguards for defendants?

Defendants have the right to a judicial review of their detention in civil court, according to a 2008 US Supreme Court ruling.

The Supreme Court agreed that the Military Commissions Act (MCA) had unlawfully deprived two prisoners, Lakhdar Boumediene and Fawzi al-Odah, of that right under the principle of habeas corpus.

But the Bush administration argued habeas corpus did not extend to Guantanamo Bay as it was not US sovereign territory and that the system it had set up itself provided adequate safeguards.

These safeguards, the administration said, are that the accused will have the presumption of innocence, and that proof of guilt must be "beyond reasonable doubt".

They cannot be forced to testify against themselves. They will have military lawyers and can also have civilian ones.

The Supreme Court ruled that detainees could seek a judicial review in civilian courts

The accused are also allowed to be present for the proceedings unless they are ruled disruptive. And they are permitted to present evidence and witnesses in their defence and to cross-examine any witnesses.

They have the right to be shown the evidence against them, though this will be in summary form if the judge decides that sources should be kept secret for security reasons.

Attorney General Eric Holder had previously said the commissions do not provide enough legal protections for defendants.

If convicted, a defendant can appeal to a Court of Military Commission Review and then to the United States Court of Appeal, a civilian court.

What drawbacks are there for the defendant?

The decision to convict is by two-thirds vote, not unanimity as in a US jury trial. The commission itself, in effect the jury, is made up of military officers not members of the public.

A key difference is that any evidence, including hearsay (in which a witness says he/she was told or heard something from someone else), is allowed if the proponent demonstrates that the evidence is completely reliable.

During the Bush administration, evidence obtained under torture was not permitted, but evidence obtained by coercion could be.

The interrogation technique of "waterboarding" was not classified as torture by the Bush administration, but Mr Obama has banned its use by the military, saying it violates American ideals and values.

Information obtained during waterboarding is no longer permitted as evidence, and the Obama administration has altered the rules of military commissions so that any coerced confession is inadmissible.

Has anyone been convicted?

In March 2007 an Australian, David Hicks, pleaded guilty to helping the Taliban and was sent home to serve a nine-month sentence.

On 6 August 2008, a six-member military jury convicted Osama Bin Laden's former driver, Salim Hamdan, of supporting terrorism.

Evidence obtained through coercion is no longer permissible in Guantanamo trials

He was sentenced to 66 months. As he had spent time in pre-trial detention, his sentence was completed in November 2008 and he was returned to his home country of Yemen.

Omar Khadr, who was a teenager when he was accused of tossing a grenade at a US soldier, pleaded guilty in October 2010 to murder in violation of the law of war, attempted murder in violation of the law of war, and other charges.

He was sentenced to eight years in prison. In September 2012 he was returned to Canada to serve the rest of his sentence.

Two Sudanese men pleaded guilty to aiding al-Qaeda - Ibrahim al Qosi, a cook, was sentenced to 14 years in prison and has been returned to Sudan.

Noor Uthman Mohammed, who helped run a camp where 9/11 hijackers trained, received a sentence of 34 months on condition that he co-operate with prosecutions against other detainees.

Why has President Obama been unable to close the Guantanamo Bay prison?

President Barack Obama made closing Guantanamo Bay a priority for his administration, promising to close it within a year of his inauguration in January 2009.

But his plan to transfer prisoners to maximum security American prisons and try some detainees in the US civilian system met steep resistance.

The plan to try Khalid Sheikh Mohammed in a New York City court prompted particular outrage.

Mr Obama's Republican opponents have opposed his plan at every step, cutting off funding for the transfer of detainees from Guantanamo to the mainland.

The US opened the Guantanamo Bay detention facility in January 2002, after the invasion of Afghanistan. About 800 prisoners have been held there since then.

When President Obama took office in January 2009, the prison held 245 terror suspects. By May 2012, that number had dropped to 169 after the administration negotiated repatriation deals with several countries.

The US suspended repatriations to Yemen after allegations that an al-Qaeda affiliated group there had attempted to blow up a US plane on Christmas Day 2009.

In April 2013, 166 inmates remained at Guantanamo.

Nearly 100 of the detainees have reportedly been cleared for release but remain at the facility because of restrictions imposed by Congress and also concerns of possible mistreatment if they are sent back to their home countries.

- Published4 April 2011

- Published7 March 2011

- Published8 March 2011