Storm leaves Alabama poultry industry in ruins

- Published

Nine of Dan Smalley's chicken houses were destroyed by the storm

On its destructive path across the southern US this week, the storm that left at least 340 dead also devastated Alabama's important poultry industry, as the BBC's Daniel Nasaw reports from Red Hill.

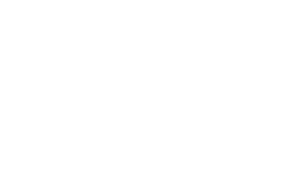

The baby chicks huddled together outside their wrecked house, dipping their beaks into a puddle of water and pecking at feed spilt across the ground.

They belonged to Dan Smalley, who owns one of the largest poultry farms in the state of Alabama. But on Saturday, they were destined not for the dinner table but to be euthanised.

In Alabama on Wednesday, the storm devastated the state's $2.4bn (£1.43bn) a year poultry industry, levelling chicken houses, killing birds and knocking out power to feed mills and processing plants.

While most of Mr Smalley's chicks survived the storm, he estimates he will lose about 200,000 birds in the coming days because the storm destroyed the facilities he needs to tend them.

"We can't care for them," Mr Smalley, 62, said as he toured the farm in a blue Ford pick up truck. "No electricity, no water."

Rebuilding ahead

Across Alabama, the storm destroyed 200 chicken houses and significantly damaged as many as 450 others.

Alabama's poultry industry is the third-largest in the US, producing about one billion meat chickens (called broilers) every year, and officials estimate it could be six months to a year before the industry resumes full production.

In general, the farmers do not own the chickens but raise them under contract with national sellers.

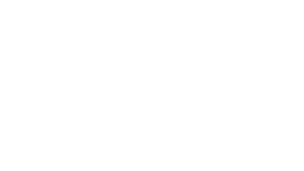

Dan Smalley has been running his farm since 1978

Farms like Mr Smalley's take day-old chicks, fatten them on a diet of corn and soy meal, and truck them out when they are six to eight weeks old to be rendered into a variety of chicken products for supermarket shelves, restaurants and fast food franchises.

Mr Smalley's birds are sold by Pilgrim's Pride, the second largest producer in the US. If you have ordered chicken from Burger King, Chick-fil-A or KFC in the US, you may have tasted one of his birds.

Although most Alabama farmers will not suffer financially from the loss of the livestock, they will have to rebuild the chicken houses and feed pens and replace destroyed heavy kit.

Insurance companies are expected to cover much of the losses.

Meanwhile, a damaged hatchery will need to be repaired and a processing plant and feed mill will have to be brought back online.

It takes 20-25 weeks for new breeder hens to mature, and three weeks for eggs to hatch.

Twisted metal

Mr Smalley's 400-acre farm, which he has run since 1978, is nestled in a quiet, narrow green valley about 40 miles (65km) from the nearest city.

On a recent afternoon, the warm air smelled strongly of chicken droppings, and the ground and virtually every structure and vehicle on the farm was covered in a dirty white quilt of chicken down strewn by the storm.

Twisted sheet metal from the chicken house roofs lay scattered across a field like old sheets of newspaper.

Nine of his 15 chicken houses - long, simple sheds in which about 20,000 chicks each spend the better part of their brief lives - were completely destroyed.

Without the ability to feed and water his chickens and to transport them to the processing plants, Mr Smalley will have to put them down, he says.

"They're what made me a living all these years," said Mr Smalley, a corpulent man with a syrupy thick southern drawl.

"We take care of them as best we can. But we're not making any money for a while, doesn't look like."

'Used to adversity'

Neighbours had stopped by to offer their assistance, but Mr Smalley told them he was not ready to receive any.

He said he had to wait for the insurance company to decide which houses he had to demolish and which could be rebuilt.

"We're going to still be in the chicken business," he said. "But to what degree, I don't know."

Guy Hall, poultry director of the Alabama Farmers Federation, predicted most chicken farmers would take the insurance money and get back to work.

"They're used to adversity," he said. "Most farmers are used to dealing with the weather.

"They're used to power outages and storms that tear things up. They're just resilient people and they're used to working 365 days a year. When you've got livestock, they've got to be looked after everyday."

- Published29 April 2011

- Published29 April 2011

- Published28 April 2011