Osama Bin Laden: The long hunt for the al-Qaeda leader

- Published

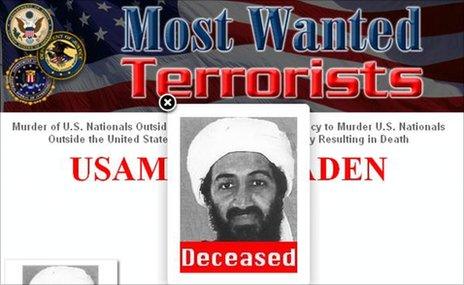

The US had offered a $25m reward for information about Osama Bin Laden

The United States sought to capture or kill Osama Bin Laden for more than 15 years before tracking him down to a compound in north-western Pakistan, not far from a large town and the country's military academy.

Although no opportunities presented themselves in recent years, there were several before 2002 - prompting many to question the power and effectiveness of the US military and intelligence machine.

US senators have said the failure to find Bin Laden forever altered the course of the conflict in Afghanistan and the future of international terrorism, left the American people more vulnerable, laid the foundation for the Afghan insurgency, and inflamed the internal strife in Pakistan.

Missile strikes

In 1996 the CIA's Counter-terrorist Centre (CTC) set up "Bin Laden Issue Station", a special unit of a dozen officers, to analyse intelligence on and plan operations against the Saudi millionaire. At the time Bin Laden was believed to be financing militants in the Middle East and Africa.

By late 1997 - after Bin Laden had been forced to move from Sudan to Afghanistan, and had called on Muslims to "launch a guerrilla war against American forces" - the unit had formulated plans for Afghan tribesmen to capture him before handing him over to the US.

Though the head of the CTC thought it was the "perfect operation", the director of the CIA decided not to go ahead with it, according to a later report issued by the 9/11 Commission's report, external.

Then, in August 1998, more than 220 people were killed when lorries filled with bombs drove into the US embassies in Kenya and Tanzania. After determining that al-Qaeda was responsible, US President Bill Clinton authorised missile strikes against militant camps in Afghanistan, including Bin Laden's compound.

The strikes failed to kill any al-Qaeda leaders and prompted Bin Laden to start changing locations frequently and unpredictably, and to add new bodyguards. He also changed his means of communication. Nevertheless, tribal sources were still able to provide regular updates on where he was.

In December 1998 it was reported that Bin Laden might be staying the night at the residence of the governor of Kandahar. But a missile strike was ruled out after generals predicted 200 people might be killed or injured. Some lower-level CIA figures worried that the US might rue the decision.

A similar opportunity to bomb a camp south of Kandahar in February 1999 was missed because Bin Laden moved on before the operation was approved.

How did the world's most wanted man evade capture for so long?

Perhaps the best opportunity to target Bin Laden came in May 1999, when CIA assets confidently reported Bin Laden's location for five days and nights in and around Kandahar. Despite officials at the Pentagon and CIA expressing little doubt about the operation's success, it was not authorised.

From then until after the 11 September 2001 attacks the US government did not again actively consider a missile strike against Bin Laden. Putting US personnel on the ground was also ruled out because of the risk of failure.

Michael Scheuer, who founded the Bin Laden unit and ran it until 1999, told the BBC: "Mr Clinton is more a citizen of the world, and he was worried about what the Muslim world would think if we missed and killed a civilian."

"He generally talked a good game that he did his best once he left office. But I happened to be there at the time, and Bin Laden should have been an annoying memory by the middle of 1998 or early 1999."

Tora Bora

On 18 September 2001, US President George W Bush famously declared that Bin Laden was wanted "dead or alive".

Bin Laden fully expected to die in the mountains of Tora Bora

The next month US aircraft began a massive bombing campaign against al-Qaeda bases in Afghanistan as part of a mission to destroy the group, kill Bin Laden and other key leaders, and to defeat the Taliban.

Military special forces and CIA teams, along with their Afghan allies, were also deployed on the ground to seize control of al-Qaeda strongholds.

Although the US and its allies declared victory that December, Bin Laden had been neither captured nor killed. He was, however, cornered in a complex of caves and tunnels in the mountainous eastern Afghan area of Tora Bora.

Under relentless attack from the ground and air, Bin Laden fully expected to die and even wrote a will on 14 December.

But fewer than 100 US commandos were on the scene with their Afghan allies and calls for reinforcements to launch an assault were rejected, according to a 2009 report by the US Senate foreign relations committee, external.

Requests were also turned down for US troops to block the mountain paths leading to sanctuary a few kilometres away in Pakistan.

Instead, commanders chose to rely on air strikes and Afghan militias to attack Bin Laden and on Pakistan's Frontier Corps to seal his escape routes.

US Defence Secretary Donald Rumsfeld said at the time that he was concerned that too many US troops in Afghanistan would create an anti-American backlash and fuel a widespread insurgency.

Two days after writing his will, Bin Laden and his bodyguards walked out of Tora Bora and disappeared over the border into Pakistan.

"Removing the al-Qaeda leader from the battlefield eight years ago would not have eliminated the worldwide extremist threat," the Senate committee report concluded.

"But the decisions that opened the door for his escape to Pakistan allowed Bin Laden to emerge as a potent symbolic figure who continues to attract a steady flow of money and inspire fanatics worldwide."

Video tapes

After Tora Bora, the hunt moved to Pakistan. Several senior al-Qaeda leaders were arrested or killed, including the alleged mastermind of 9/11, Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, but there were very few leads of Bin Laden himself.

Pakistan's government dismissed reports that he was in the country, but it was widely believed that he was moving from village to village in the north-western region of Waziristan with a small group of bodyguards, where he would live under the protection of Pashtun tribal leaders.

Some believed the failure to capture or kill Bin Laden was the result of collusion by Pakistani officials

Bin Laden was believed to communicate only once a month by courier, and never by telephone. He nevertheless managed to record video and audio messages which were either passed to media organisations, most notably al-Jazeera, or published on the internet. His last video tape was released in September 2007, while his last audio message came in January 2011.

Former CIA agents said the main obstacle to finding Bin Laden was that anyone who might consider betraying him for the $25m reward offered feared informing local police, in case they were sympathetic to or in the pay of Bin Laden.

Also, the agents themselves were prevented from venturing far from their compounds in Pakistan because of the threat of assassination and resistance by the intelligence arm of the Pakistan military, the Inter Services Intelligence Directorate (ISI), which wanted to lead the operation.

Confronted with such obstacles agents instead relied on electronic intercepts, aerial photographs, and information collected by the ISI's spies. Leads were followed up by local proxies, who often risked their lives. One cleric was beheaded after being sent to Waziristan.

Even when a senior al-Qaeda figure was identified and located, it often took weeks to get approval from the Pakistani authorities for an air strike.

Andrew Card, President Bush's former chief-of-staff, told ABC News: "The intelligence would frequently tease us. We would think that we were close to getting him. A couple of times we thought we actually got him, but we didn't."

Some US officials believed the failure to capture or kill Bin Laden and his deputy, Ayman al-Zawahiri, was the result of collusion by their Pakistani counterparts, particularly those within ISI. Some claimed the ISI was harbouring the two men.

"I'm not saying that they're at the highest levels, but I believe that somewhere in this government are people who know where Osama Bin Laden and al-Qaeda is," US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton said in May 2010.

The discovery that Bin Laden had been living in a large, custom-built, walled compound in Abbottabad close to Pakistan's military academy - possibly from as early as 2005 - has reinforced suspicions about the ISI.

US officials have said it took eight months for US and Pakistani agents to confirm the location of the al-Qaeda leader, and that they found it by trailing one of his most trusted couriers, whose name was revealed by detainees.

But former CIA field officer Bob Baer told the BBC that he was sceptical about the assertions that Bin Laden had been traced through a courier.

"Intelligence agencies like the CIA and the US military will simply put out disinformation to protect the real sources, which could have been anything from intercepts to the Pakistani government itself," he said.