William Randolph Hearst: Mythical media bogeyman

- Published

William Randolph Hearst was a dramatic innovator in journalism

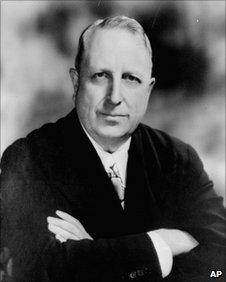

William Randolph Hearst lives on 60 years after his death as the mythical bogeyman of American journalism, the personification of the field's most egregious impulses.

Hearst is typically remembered as the irresponsible media tycoon of the late 19th and early 20th Centuries who set standards by which journalism ought not be practised.

That reputation is not altogether fair, and yet not altogether surprising.

Hearst was a contradictory figure and his inherited wealth made him readily unlikable.

As David Nasaw, one of his leading biographers, has written: "William Randolph Hearst was a huge man with a tiny voice; a shy man who was most comfortable in crowds; a war hawk in Cuba and Mexico but a pacifist in Europe; an autocratic boss who could not fire people; a devoted husband who lived with his mistress; a Californian who spent half his life in the East."

It's little wonder why Hearst was, and remains, the object of so much myth and misunderstanding.

As heir to his father's silver fortune, Hearst, a Harvard drop-out, entered the newspaper business at the top, as publisher of the San Francisco Examiner.

In 1895, he went East to buy the New York Journal, which he turned into a flamboyant daily that gave rise to the epithet "yellow journalism".

Hearst invited the contempt of fellow journalists.

Did Hearst start a war?

After all, didn't he famously vow to "furnish the war" with Spain in 1898?

Didn't he make good on that vow by fomenting the war?

Citizen Kane - played by Orson Welles (centre) - was loosely based on Hearst

And didn't he anticipate Rupert Murdoch and his multimedia empire?

Well, no, no, and not exactly.

Let's consider each myth in turn.

Hearst almost certainly never promised to "furnish the war," or anything akin to such a vow.

The anecdote, though, is perhaps the single most-repeated tale in American journalism.

It stems from a cable Hearst supposedly sent to the artist Frederic Remington, whom Hearst had assigned to Spanish-ruled Cuba in early 1897, to draw sketches of the rebellion then sweeping the island.

No-one has much noticed, but Hearst denied having sent such a message - which Spanish censors surely would have intercepted, had it been sent. The cable itself has never turned up.

Nor did Hearst's newspapers bring about the Spanish-American War. That conflict, in the final analysis, was the consequence of a three-sided diplomatic impasse that was far beyond the power of the Hearst Press to control or much influence.

Parallels to Murdoch

The parallels to Murdoch, while intriguing, are mostly superficial and deceptive. Hearst never developed anything akin to the global media empire that Murdoch has established.

Unlike Hearst, Rupert Murdoch has never sought political office

And Murdoch, a naturalised American citizen, never pursued the political ambitions that animated but mostly eluded Hearst.

Hearst used his newspapers as a platform and pursued the Democratic Party's nomination for president in 1904. He failed.

Later, he ran for governor of New York State and mayor of New York City, but lost those races. By 1910 or so, Hearst's ambitions for high political office were mostly spent.

The towering mythology that envelops Hearst began to take hold long before his death on 14 August 1951.

The lore dates to the late 1930s and the first in a succession of wretched biographies about Hearst.

Among them was Imperial Hearst, a truculent work that excoriated Hearst's increasingly conservative politics and resurrected the "furnish the war" myth.

Razing Kane

Even more important in the mythmaking about Hearst was Orson Welles's cinematic masterpiece, Citizen Kane.

Hearst portrayed as a spoilt child about to break his doll in a 1930 cartoon

The movie was based loosely on Hearst's life and times, and received mostly mixed reviews when it was released in 1941.

Hearst did try to have the film killed, which served to enhance its latent appeal. Kane was rediscovered in the 1960s and ultimately gained deserved recognition as a classic.

A rollicking scene in the movie borrows from and paraphrases the "furnish the war" anecdote, which further helped to implant the myth in the popular consciousness.

The mythology has obscured the recognition that Hearst, at least in his early years in journalism, was a dramatic innovator.

During the closing half of the 1890s, Hearst in New York pursued an activist vision of journalism, a typology he called "the journalism of action".

By that he meant newspapers had an obligation to inject themselves prominently and routinely into public life, to address the ills that government couldn't or wouldn't.

'Journalism of action'

As Hearst envisioned it, the "journalism of action" was to be a sustained force, defined by activism on many fronts and fuelled by frequent doses of self-promotion and self-congratulation.

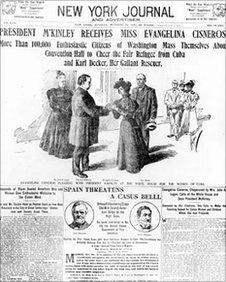

President McKinley meets Evangelina Cisneros, as seen by Hearst Press

The zenith of the "journalism of action" came in October 1897, when a reporter for Hearst's Journal led the jailbreak in Havana of a 19-year-old political prisoner named Evangelina Cisneros.

The reporter, aided by several Cuban accomplices, managed to slip the young woman aboard a passenger steamer bound for New York, where Hearst organised a tumultuous reception to welcome her.

In important respects, Hearst's "journalism of action" echoed the British investigative journalism pioneer William T Stead's advocacy of "government by journalism," which he proposed in the mid-1880s.

Stead was a central figure in Britain's "new journalism" movement of the late 19th Century. He argued that the newspaper editor, in his capacity to frame and shape public opinion, represented "the greatest force of politics".

By applying "either a stimulant or a narcotic to the minds of his readers", the editor could bring to bear decisive influence on the important matters of the day, Stead maintained.

Hearst's commitment to the "journalism of action" was eventually overtaken by his political ambitions and by a rival paradigm advocated by Adolph Ochs of the rival New York Times.

Ochs, who acquired the nearly bankrupt Times in 1896, advocated a detached and even-handed approach to newsgathering - the antithesis of the "journalism of action".

Ochs's vision of impartial treatment of the news ultimately prevailed, and nominally remains the defining standard for mainstream American journalism.

Sixty years on, the mythology surrounding Hearst and his reputation may run too deep ever to be expunged.

W Joseph Campbell is a professor in the School of Communication at American University in Washington, DC. He is the author of five books, including Yellow Journalism: Puncturing the Myths, Defining and Legacies and The Year That Defined American Journalism: 1897 and the Clash of Paradigms. He blogs about journalism history at Media Myth Alert, external.