Bill Bratton: How 'Supercop' cleaned up US cities

- Published

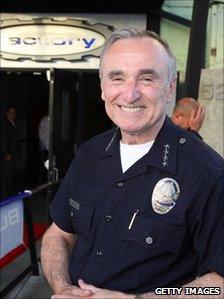

Bratton emphasises his 'progressive' policies

The American police officer advising the UK Government about crime in the aftermath of the riots has been characterised as "Supercop" in the British media. But is Bill Bratton really the tough-talking, zero-tolerance cop that his reputation suggests?

When William Bratton became a police officer in Boston at the age of 23, it was the fulfilment of a childhood dream.

Television police shows like Dragnet had fired the young Bratton's imagination and in 1970, he at last entered those hallowed ranks.

British Prime Minister David Cameron was only four at the time, but 40 years later he is drawing on the wisdom of the American after nights of unrest in English towns and cities, despite opposition from senior British police officers.

Due to an illustrious career in which he has arguably transformed the fortunes of three of America's biggest police forces, the 63-year-old Mr Bratton has been dubbed "Supercop" in the UK media.

The phrase "zero tolerance" is not far behind, reinforcing the image of a no-nonsense, tough guy, much like the stereotype American "cop".

That British perception stems very much from his time in New York, when he transformed the fortunes of the city by taking a very hard line on petty crime.

In an hour-long speech to the Policy Exchange, external think-tank in London last year - one of many visits to the UK - he said New York resembled a "Mad Max movie" in 1990, with aggressive beggars, muggings and graffiti-covered subway trains. It was the "poster boy" of a country in disarray.

Police had wrongly been obsessing about their response to crime, rather than preventing it, he said, and ignoring the "quality of life" issues that created fear in neighbourhoods.

Appointed by Mayor Rudy Giuliani in 1994, he adopted the so-called broken windows theory, external that suggests tackling anti-social behaviour with a strong arm has huge benefits in preventing violent crime.

But he also fully embraced the community policing phenomenon that emerged in the late 1980s - the belief that police officers should engage with the public, be seen on the streets and join as partners with the judiciary and community organisations.

This dual approach, backed by the arrival of 5,000 newly trained officers, brought immediate results, with huge falls in crimes across the board, particularly murder.

He had fewer resources at his next big job, in Los Angeles, which presented a different challenge - gang violence in a smaller city spread over a larger geographical area.

The man who hired him was the mayor at the time, James Hahn. Now a judge at the Los Angeles County Superior Court, Mr Hahn recalls the bullish man he interviewed in 2001.

"He said in the interview that he would reduce crime by 25% or he would leave. Each year he would do something I have never seen a police chief do. He called them 'stretch goals' and he would say 'I'm going to reduce crime by, say, 15%.'

"Most people brag about it at the end of the year, but Bill would commit to this at the start of the year. And he would not only meet the targets but exceed them."

In three years, he reduced crime in the city by 40%, says Mr Hahn, but just as importantly, his honest leadership restored morale to a flagging department.

"We were losing officers faster than we could hire them. It wasn't a money problem, because they would go and work for other police departments with a better working atmosphere.

"The rank and file at first was very suspicious of this outsider who had not come up through the ranks but they came to respect him because he's a no-nonsense, plain-talking guy."

Bratton's links with the UK go back years

Community relations improved because he introduced a more diverse recruitment policy and the police were seen to be engaging with Hispanic and African-American communities.

There was criticism about the time he spent away from the city, at conferences in other parts of the country, but Mr Hahn says he didn't care because he got results.

"The thing I'm most proud of in my brief tenure as mayor was to reverse three years of rising crime, and Bill Bratton was the reason I achieved that goal."

And as a person, he's charming and fun to be around, says Mr Hahn, with a self-deprecating humour which the British will appreciate.

He appears to be a keen student of British policing, referring in the past to the "phenomenal wisdom" of Robert Peel, who he says shaped his thinking. And he has expressed a strong interest in the vacant position running the Metropolitan Police, although it is only open to Britons.

An interview with the Guardian newspaper, external this week suggests he himself would prefer to emphasise his community-building skills, rather than his zero-tolerance methods.

But his critics say his reputation is burnished by the fact that long-term crime trends in the US have been falling anyway, for a number of reasons.

One of the country's leading criminologists, Professor Alfred Blumstein, prefers to give Mr Bratton credit, saying the drop in New York crime was greater than elsewhere and he repeated the trick in LA during a period when crime nationally was pretty flat.

"I've developed a high regard for Bill Bratton. He brought some important innovations to New York, including the highly regarded and widely replicated Compstat management system.

"That system used fast-response computerised information on crime to hold precinct commanders for reducing crime in their precincts, and that management shift was an important contributor to lowering crime rates in New York."

His restructuring of the ethnic composition of the police department in Los Angeles and improving community relations there shows he can tailor his skills to different problems, says Mr Blumstein.

"That wisdom and those skills will allow him to bring important insights to policing in the UK.

"Also, he's a very low-key individual, so I'm confident he won't come roaring in as a Mr Know-it-all, which would certainly be a serious turn-off in the highly respected Scotland Yard.

"I've talked to him about various aspects of crime and criminology and there's always a very open atmosphere in dealing with him. He's not like a Supercop."

- Published15 August 2011

- Published12 August 2011