BerkShares boost the Berkshires in Massachusetts

- Published

Within two years residents should be able to take out loans in BerkShares - an important indicator of the US currency's health.

Tucked away in the western corner of Massachusetts, the rolling hills of Berkshire County seem an unlikely front line in the battle against globalisation.

But that was before the financial collapse of 2008, the current European debt crisis and fears of a double-dip recession in the US.

Now the world is watching how the community of 19,000 people is surviving the global economic turmoil - by using BerkShares instead of dollars.

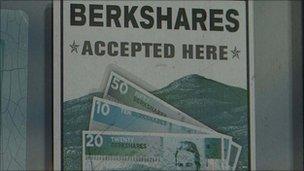

"BerkShares are our own personal local currency backed by US dollars," explains Nancy Fitzpatrick, owner of the Red Lion Inn in Stockbridge, one of 400 businesses that accept BerkShares.

"It's an affirmation of our local economy and an indication that I support our small local businesses, that my dollars will be spent within Berkshire County."

Three million BerkShares have been issued since the legal currency was launched seven years ago and 130,000 remain in circulation.

They're worth slightly more than a dollar - the equivalent of a 5% discount. For example, a $100 dinner at the Red Lion costs $95 if the customer uses BerkShares.

The Red Lion then uses them to pay the area's farmers, who supplied the fresh vegetables. They in turn will come back to the town to spend their BerkShares at local stores.

"The whole idea is not to bring them back to the bank because BerkShares have the most power in circulation. The money never leaves the community and everybody is richer for it," says Stefan Root, owner of Berkshire Bike and Board in Great Barrington.

He believes the currency has the potential to protect communities from fluctuations in the global markets that can affect everything from pensions to the price of produce.

"The idea that we have to belong to a globalised market is proving to be unsustainable. Our global economy is based on growth and if there's no growth the economy collapses.

"The BerkShares are highlighting that we can survive by producing things locally. How you spend your money and where you spend your money is actually very important."

But he admits committing to BerkShares is tough because so much is sourced overseas, including bicycles he sells which are made in China. "And the Chinese don't accept BerkShares."

Fulfilling a community

It's a problem experienced by other businesses in the Berkshires and demonstrates the practical limits of any local currency.

Joe and Darleen Wilkinson have been running their family excavating business in Sheffield for 40 years. They began accepting BerkShares because they wanted to support their community.

Local currencies have been launched around the US and the UK to strengthen a regional economy

But the large amounts of money associated with their industry meant few customers were willing or able to pay in anything other than dollars.

"Few people will come to us with $10,000 worth of BerkShares in cash," says Mr Wilkinson.

"And in some cases, if we're doing something big, they'll have to borrow the money to pay.

"We're limited in how much we would get in BerkShares in our type of business - no question about it."

Mrs Wilkinson estimates that they've collected no more than $2,500 in BerkShares over the last four years. And re-circulating even that amount has proved difficult.

"We buy a lot of materials from out of town and most places don't take them so we don't have the option to spend them on purchases for our next job," she says.

Closing such gaps in the supply chain is the next planned phase in the currency's development.

New businesses aimed at fulfilling a community need will soon be able to apply for loans on condition that 25% of the money is issued in BerkShares.

"Sometimes people run out of things to do with their BerkShares and this would give them the opportunity to reinvest their surplus," says Nick Kacher of the New Economics Institute, which supports BerkShares.

"BerkShares are an experiment. The currency was started as a way of figuring out how to use capital as a tool to strengthen communities.

"The current version appeals to some people, but not everybody. The novelty is starting to wear off but the loans will make them fresh again."

The maple syrup index

Based on a model started in the state of Washington, the loans could become available within two years. And there are also plans to decouple Berkshares from their dollar pegging.

That move gained momentum in July when Congress struggled to reach agreement over the best way to reduce the country's enormous budget deficit.

Until a deal was reached, the US faced defaulting on its loans for the first time in history because Republicans in the House of Representatives refused to raise the debt ceiling.

"We had a lot of people asking, if the dollar collapses, will the BerkShare hold its value - and the answer was no," says Mr Kacher.

"BerkShares need to be backed by a local commodity, in our case, food produced in the Berkshire region."

The value of the dollar is determined by national and international markets, which Mr Kacher says don't necessarily reflect what is going on in Berkshire communities.

"But if the currency was backed by a local commodity, such as maple syrup - so 10 BerkShares would buy a gallon of maple syrup - then whatever happens to the markets or the value of the dollar, 10 BerkShares would always buy a gallon of maple syrup."

Many businesses find it hard to operate in Berkshares only and remain reliant on the US dollar

In that scenario the BerkShare would join a floating exchange. If the price of producing a gallon of maple syrup went up, it would cost more dollars to buy, not more BerkShares.

The exchange rate would change, not the value of the commodity.

It's an economic model that has become popular in other parts of the US and in the UK. London has launched the "Brixton Pound" and the "Totnes Pound" can found in Devon.

Most recently a community in Baltimore, Maryland, introduced the Baltimore BNote.

"People look at what's happening at the moment and they see the economy as a vast thing beyond their control. But this is about making capital work for us," says Mr Kacher.

"We have these resources within our communities, the issue is how can we strengthen them and use them to make people's lives better?"

But other analysts say the idea will never become part of mainstream economic thought.

"They're a rejection of globalisation and come from a strong sense of community," says Mark Calabria, director of financial regulation studies at the Cato Institute, a libertarian think tank in Washington DC.

"But I have a hard time seeing them as more than niche. They'll continue to be interesting but they're not a competitor to the dollar."