REM: The band that defined, then eclipsed college rock

- Published

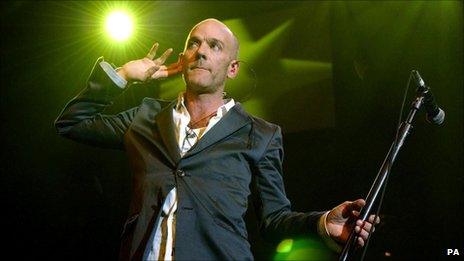

Michael Stipe said the band was influenced by its small-town roots

The story of REM is in many ways the story of alternative rock in the USA.

They emerged in the early 1980s from the college radio scene - scrappy and lo-fi, abrasive but somehow beautiful - blossoming into bona-fide stadium-fillers only in the second decade of their career.

"We were the band that had no goals," Michael Stipe told the BBC earlier this year, while promoting REM's 15th and final album. In hindsight, it was telling that he was by himself.

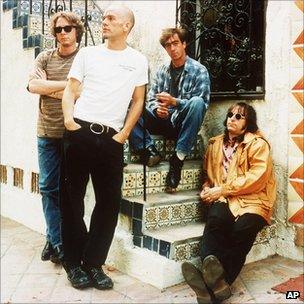

The group - Stipe, guitarist Peter Buck, bassist Mike Mills and drummer Bill Berry - played their first gig in a church on 5 April 1980.

That night they were still called Twisted Kites, and they played a mixture of original material and covers, including the Sex Pistols' God Save the Queen and Jonathan Richman's Roadrunner.

"It was really fun," Stipe said later, "but I don't remember the last half of it."

Small town

The band quickly found a following, their mixture of post-punk poise and jangly, Byrds-esque guitar making them seem simultaneously cutting-edge and a romantic reminder of rock's past.

Mike Mills said the sound was explicitly informed by their small-town surroundings in the "out-of-the-way" town of Athens, Georgia.

"If you grew up in New York or LA, it would change your viewpoint on just about everything," he wrote in a 1985 edition of Spin Magazine. "There's no time to sit back and think about things."

"Our music is closer to everyday life - things that happen to you during the week, things that are real.

"It's great just to bring out an emotion... better to make someone feel nostalgic or wistful or excited or sad."

Pathologically shy, Stipe's vocals were largely unintelligible on early singles like Radio Free Europe and So, Central Rain. But, as the band found their footing musically, so did he as a lyricist.

Losing My Religion music video courtesy of Warner Bros

The breakthrough, commercially speaking at least, was The One I Love - a single from their 1987 album, Document, which unexpectedly hit the US top 20.

More driven and direct than their folksy early singles, it began with a crashing drum-fill and a menacing, vibrato riff from Buck, before Stipe intoned: "This one goes out to the one I love. This one goes out to the one I've left behind."

On the basis of those lyrics, the song is frequently requested by lovestruck couples on radio phone-in shows.

They have seemingly missed Stipe's barb that the subject of the song was "a simple prop to occupy my time".

"[The One I Love] is incredibly violent," he admitted to an interviewer in 1988. "It's very clear that it's about using people over and over again."

'Freaks'

With the song, REM suddenly outgrew the college radio circuit, the university-centred underground scene which had sustained their careers over the course of five increasingly confident albums.

REM went from church hall performers to world rock megastars

For some purists, the band never recovered. Snatched away from independent label IRS by mega-corp Warner Brothers, then home to 80s stars Prince and Madonna, they were seen as sell-outs.

As comedian Stewart Lee put it: "I don't think there's anyone whose career trajectory has been so disappointing, starting so brilliantly and end[ing] up just so dreadful."

But Stipe, too, had qualms about the band's new audience.

"I had to grapple with a lot of contradictions back in the 80s," he told the Guardian.

"I would look out from the stage at the Reagan youth. That was when REM went beyond the freaks, the fags, the fat girls, the art students and the indie music fanatics.

"Suddenly we had an audience that included people who would have sooner kicked me on the street than let me walk by unperturbed."

"I'm exaggerating to make a point but it was certainly an audience that, in the main, did not share my political leanings or affiliations, and did not like how flamboyant I was as a performer or indeed a sexual creature. And I had to look out on that and think, well, what do I do with this?"

In part, the answer was to raise his game. The band's first release on a major label, 1988's Green, was seen by some critics as their true peak.

Stipe's voice had a new clarity of tone, while producer Scott Litt brought a tight focus on the band's burgeoning musicality.

Lyrically, the album saw the band turn to face the world around them. World Leader Pretend is a deft criticism of the remote ruling classes - "I proclaim that claims are left unstated" - while Pop Song '89 neatly tackles claims the band had sold out by purporting to be, in Stipe's words, "the prototype of, and hopefully the end of, a pop song".

Out of time

Green sold more than a million copies in the States, but even that was to be eclipsed by the band's next album, Out Of Time.

REM won three Grammys in 1992

Featuring the career-defining singles Losing My Religion and Shiny Happy People (a track the band came to detest), it entered the charts at number one on both sides of the Atlantic.

It's one of the few albums in the history of rock where a band is clearly aiming to make a massively successful, mainstream record and succeeds without embarrassing, or compromising, themselves.

Overflowing with melody and harmony - thanks to Mills' floating falsetto and guest appearances from fellow Athenian Kate Pierson - it is at once sincere and shivers-down-the-spine emotional.

Losing My Religion is a touchstone of alternative rock - Stipe's plaintive cry that "I don't know if I can do it" delivered with such an aching sadness that you can never quite be sure whether he is talking about faith, the loss of love, homosexuality or his fragile relationship with fame.

Those inner demons came to the fore more strongly on 1992's Automatic For The People.

A more sombre, reflective album, with string arrangements by Led Zeppelin's John Paul Jones, it nonetheless featured Stipe goofing around on the single The Sidewinder Sleeps Tonite, a single that leaves intact a vocal take where the singer collapses in fits of laughter.

Everybody hurts

After spending months in the studio poring over the intricate arrangements of their previous two albums, the band's next records Monster and New Adventures In Hi-Fi were largely recorded live - some tracks on the latter literally taken from tapes at soundchecks on a massive stadium tour.

They featured some new classics - Let Me In, a tribute to the recently deceased Kurt Cobain, remained part of the band's setlist for years to come - but nothing quite achieved the artistic peak of the earlier albums.

After drummer Bill Berry suffered a brain aneurysm and quit the band in 1997, things never quite returned to an even keel.

Moments of brilliance, such as The Great Beyond or Imitation Of Life, seemed to crop up with increasingly less frequency.

Stipe was perhaps distracted by his film work - producing the likes of Being John Malkovich - while the rest of the band pursued side projects, including Peter Buck's country supergroup Tired Pony.

They continued to be unbeatable live performers to the end. Everybody Hurts was capable of reducing entire audiences to puddles of tears, even on its 1,000th outing.

REM's final album, Collapse Into Now, was released in March this year and was hailed - as were so many of its predecessors - as a return to form. Certainly, the band sounded rejuvenated and energetic after the stately torpor of their work in the mid-2000s.

By the closing track, Blue, Stipe was able to bellow: "This is my time, and I am thrilled to be alive!"

And perhaps, that is as good a point as any to say goodbye to one of the most influential bands of their generation.

- Published22 September 2011