Migrants ride 'the Beast' from Mexico to the US

- Published

Mexican actor Gael Garcia Bernal has spoken with migrants from across Central America who are trying to reach the United States

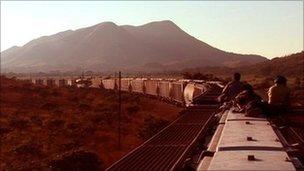

Every year, thousands of undocumented migrants cling to the wagons of "the Beast", a freight train that runs from southern Mexico to the US-Mexican border, braving bandits, immigration officials and the elements to reach "El Norte".

The BBC spoke to two who survived the perilous journey and made it to California.

Frida Hinojosa, Mexican migrant

Frida Hinojosa says she would make the journey again if she had to

To get to Los Angeles, California, where she has lived since crossing the US-Mexican border without documents five years ago, Frida Hinojosa left her tin shack in Southern Mexico ready to board the "Train of Death".

"It was a fearful journey, filled with uncertainties. Those were probably the worst days of my life," she says.

By train, Ms Hinojosa travelled about 1,100km (684 miles) from the city of Tapachulas, near the border between Guatemala and Mexico, all the way to Mexico City.

"Los garroteros [people armed with garrottes] were running from coach to coach in the middle of the night, asking for money," she says. "They said that even though the train was free and we had not paid for a proper ticket, we had to pay them to be able to ride. And if you had nothing, they would just abuse you, verbally or physically."

The migrants face bee attacks in the Mexican jungle, dehydration, hunger, and violence

The train, she says, was the only means to get to the North, as she had very little money and no job, and most of those who ride the Beast take between 10 and 15 different trains to cover the distance.

The train is most dangerous for women, many of whom are raped or coerced into performing sexual favours in exchange for protection.

"I was travelling on my own and, as a woman, really bad things happened. It was very sad. I had no money and most of what I got from begging at every train stop I had to give to others, who would then look after me."

"The Beast is a much worse place for women than it is for men," she says.

From Mexico City she continued by bus, stopping in Guadalajara, where she worked to raise money to pay the "coyote" to guide her over the border. She finally reached Tijuana, a border city on Mexico's west coast. On the other side of the fence lay San Diego, California.

Her son joined her in Los Angeles 18 months later. She is now married to a Guatemalan who helped her get the documents that allowed her to remain in the US legally.

"I saw so many sad things," she says.

"I saw a mother whose child died on the train and had to bury him on the Mexican side of the border before continuing her journey. I saw rapes, I saw murders. Knowing that I was doing this for my son gave me strength and hope to keep going. Now he's a grown-up, God bless him, and we are together."

Most migrants carry little: a change of clothing, money for bare essentials, maybe a mobile phone

Ms Hinojosa is unemployed, a situation she blames on the US economy. But going back home is not an immediate option for her.

Would she brave the Beast again?

"Of course I would," she replies without hesitation.

"All I got here makes it worth the ordeal. I wouldn't have achieved anything if I had stayed [in Mexico]. Most migrants on the train shared a dream, we are in it together."

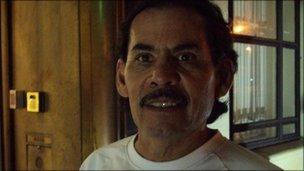

Omar, migrant from El Salvador

Omar failed in his first attempt to reach 'El Norte' and was deported back to El Salvador

Omar, a construction worker who now lives in Los Angeles, started his journey as an undocumented migrant in January 1990.

"Things back then were slightly different, less dangerous perhaps than what they are now," says Omar, who asked the BBC not to use his surname.

He boarded a bus in his native Apopa, a small town in central El Salvador. To reach the US-Mexico border, he first had to travel through Guatemala and Mexico.

A four-day bus ride left him in southern Mexico, ready to board the Train of Death.

"The cargo trains didn't stop, you had to jump on board before it was gone," he says.

"At the beginning it was scary. I let one train go past because I thought I couldn't do it. Then I got used to it. But it's true that your physical abilities determine whether you make it all the way north or you just give up or suffer an accident that can be fatal."

Back then, he recalls, migrants did not have to reach the roof of the carriages for their clandestine journey.

Train guards would open an empty coach for them, with no seats or ventilation, and would seal the doors in between stops.

He travelled for hours jammed into a car with about 200 fellow migrants and suffered severe dehydration.

He had his first glimpse of southern Mexico in the state of Chiapas, where the train made its first stop. He spent the night at a shelters for migrants volunteers had set up along the road.

"I was emotionally drained," he recalls. "I saw people dying falling from the metal stairs of the Beast, some of them mutilated under its wheels. I started thinking that it was harder than I'd been told. I didn't know if I could do it."

Days later, he ran into immigration officers and was deported back to El Salvador.

The majority of the Beast riders are Salvadoran, Guatemalan, or Honduran

Six months after that he tried again, asking an acquaintance to guide him in exchange for money.

"Sexual abuses were common, as well as extortions from the authorities who asked for a "mordida" [bribe] to let us go through a checkpoint," he says.

He was mugged and beaten on board the Beast. He also lost all his money: he had given it to a woman he had befriended, thinking that it would be safer with her, but she was also attacked.

To raise the cash to continue, he worked for a month as a cleaner and gardener for a wealthy elderly couple of Russian origin in Tonalá, in the state of Jalisco.

"They wanted to help and let me sleep in their garage during the night," he says.

The memories of the train, he says, are still engraved in his body.

"I've never felt such heat in my life," he recalls.

"Every time I feel extreme heat, all those memories come back. I saw my own death, I felt it and it felt so real while I was riding that train."