Where the jobs are: Will skilled labour pay off?

- Published

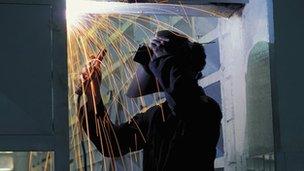

In the US, welders make an average of $16.26 (£10.14) an hour

When the gypsum mines in Empire, NV closed, the town almost shut down as well.

It was another example of the declining American economy, except for one big factor: while Empire turned into a ghost town, the miners fared better, and quickly found new jobs in mines located elsewhere.

That's because mining is one of the job markets where employers are seeing a shortage of trained workers - even as unemployment overall remains high.

"Depending on whose estimates you want to believe, there's 400,000 to 750,000 vacancies in the skilled trades," says Thom Ruhe, director of entrepreneurship at the Kauffman Foundation, a US-based research, education and policy organisation.

The lack of skilled labourers made headlines in 2006 and 2007.

While the recession has reduced demand - fewer companies are building and manufacturing, resulting in a decline in the need for skilled workers - it hasn't eliminated the core problem. A report from the global ratings agency Fitch Ratings, external, published this July, says that high unemployment shouldn't distract from the potentially costly shortages in several industries, including mining and IT.

"Even within the downturn, there's been evidence of very specific skills that employers have had a hard time finding," says Harry Holzer, a professor of public policy at Georgetown University in Washington DC.

Educational barriers

For job seekers hoping to capitalise on the shortage, it's not as easy as deciding to enter the field. The very nature of these jobs are that they require specialised training, which poses several challenges.

The first is that training takes time, and job seekers desperate for economic relief aren't always able to devote the months or years required to become qualified.

"I don't see a lot of people going to night school for nursing, and I don't see a lot of people going to night school for engineering," says Immanuel Ness, professor of political science at Brooklyn College in New York. "It requires a lot of training, and I don't know if it could be a second career."

The other, larger problem is that the educational infrastructure hasn't yet caught up to the demand from workers who do want to make the switch or update their skills.

"A lot of people went back to community college in 2008 and 2009. They did know the one field where there are jobs seemed to be health care, but they didn't get into the classes," says Holzer.

Teaching these skilled fields can require expensive equipment and lots of time in a classroom.

"You can't teach nursing on a computer, or welding on a computer," says Ness.

As a result, these classes expensive for schools to offer, and what programmes do exist are quickly filled.

Some skilled trades are taught through apprenticeships or on-the-job training, but that type of knowledge transfer is less common than it once was. Companies are reluctant to invest in training workers below the managerial level, says Holzer, for fear that workers will then leave for competitors. While unions had stepped in to fill that gap, they've become less prevalent on the America landscape.

A new education

Experts say a more long-term approach to the problem is necessary, one that involves a re-imagining of the American education system.

"There is a disconnect in thinking that all worthwhile knowledge comes out of college," says Mike Rowe. The host of Dirty Jobs on the Discovery Channel, Rowe set up a foundation, external in 2008 to raise awareness of vocational careers.

While he supports the value of a college education, he says, the idea that a four-year university is the only way to succeed is a damaging one, and one that steers people away from worthwhile careers in a trade.

"We don't put the options on the kitchen table that we used to," he says of career paths that are presented to children. "When we do put skilled trade occupations out there, we don't really present them as fundamental or aspirational options."

School curriculum reflects that, says Mr. Ruhe of the Kauffman foundation. "We've drubbed out vocational education from the schools," he says, so that most students are prepared for and sold on the college experience without being able to consider other paths.

Both Holzer and Rowe point to the apprentice system in countries like Germany, which both promotes skilled labour in the general culture and provides educational alternative to classroom learning and university tracking.

Restructuring American education to be more inclusive of vocational careers could help not just future employment numbers, but the entire American economy.

As Joel Kotin points out this week in New Geography magazine, external, the US workforce "is expected to grow by over 40% between 2000 and 2050. In contrast, during the same period the number of entrants to the labour pool will decline by 25% in the European Union and Korea and plummet over 40% in Japan."

This boom in young workers, thanks to increasing fertility rates, could lead to an increase in spending and productivity - but not until the system has time to change.