Cost of prison prompts change in US states

- Published

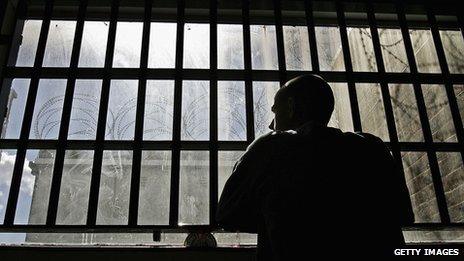

After a few minutes in Baton Rouge Parish prison you forget what the sky looks like.

Men lie on bunks, wait to make a call, watch daytime TV. Guantanamo-orange jumpsuits are everywhere.

You don't have to spend much time in the American criminal justice system to become overwhelmed by the waste, the futility and the failure.

Dennis Grimes is the warden at the prison. He has spent 27 years in these places.

"We are always at our capacity," Mr Grimes says. "Always. As soon as we let some of them out there's nearly always that many coming in."

Louisiana has the highest incarceration rate of any US state. One in 55 of its residents are behind bars.

'A party without women'

"It's just been a trend that's kept going," says Mr Grimes as he walks around his prison. "I think they just believe that if you put them in jail, put a criminal in jail, you don't have to worry about them no more."

Does it stop crime?

"Doesn't seem like it," he laughs, a big dry chuckle going through his big frame. "Doesn't seem like, 'cause this thing is still rolling."

Just under half of those released from prison in the US will be back there within three years. And failure does not come cheap.

It costs $27,000 (£17,650) to hold one prisoner for a year. Last year, US states spent $50bn on incarceration.

Criminal justice professionals have a phrase that sums up the financial challenge: the "million dollar block" - a city neighbourhood where a million dollars a year is spent locking up people from a single block.

And then there is what might be called collateral damage from time spent in prison.

"Like a party without the women" is how Antoine, a former crack dealer, describes it.

The prisons he went to are rife with drugs and rich in criminal-learning experiences.

At 31 years old, he has spent the last 15 years of his life going through the revolving door of state and federal penitentiaries. He saw his two children, now six and 12, in between.

Lawmakers balk

Lori Hart, a church administrator who helps organise programmes for ex-inmates, sees the impact on her community in Baker, Louisiana.

From 1988 to 2007, Texas had quadrupled prison numbers - but now they are being closed

"We see this in the church," Ms Hart says. "We see the children who don't have shoes on their feet. Most of the time their father is locked up or dead.

"There are fatherless homes, these children walk the streets and they are failing, it is having a huge impact on the school systems, on the community."

Across the US, prison numbers have exploded in the past three decades. Now some states - led by those once most enthusiastic about throwing away the key - are trying to call a halt.

In 2007, Republican legislators in Texas were given a bill for $2bn - what it would cost to build 17,000 new prison places in years to come. The state had nearly quadrupled prison numbers between 1988 and 2007.

But this time lawmakers blinked, balked, and instead found $250m for treatment programmes. These programmes - for non-violent offenders - range from alternative courts for military veterans to drug rehab using cognitive behavioural therapy. Texas is now closing prisons.

Such programmes appeal across the political right. It pleases social conservatives that many rehabilitation programmes are faith-based, and that many concentrate on keeping families together.

Above the entrance to the SMART substance-abuse therapy centre outside the Texas state capital, Austin, the line "where change begins" welcomes you in.

Criminal thinking

The paintwork is institution-pastel and the residents - here for five months of treatment - sleep in dorms. A whiteboard lists details for parole hearings and the like.

Here clients come after what has often been a long journey through drink, drugs, crime and punishment.

The staff know why the programme is popular with lawmakers.

"The reason we have support," says one counsellor crisply, "is that we save so much money."

So fiscal conservatives are on board too.

Jane Scott, 43, is a graduate of the unit. "Something happened at SMART when I got here," Ms Scott says.

She started drinking at 14, meandered through nearly every drug there is, and ended up hooked on crack cocaine. She was on the streets and in and out of prison for seven years.

"I had to accept where I was at, that my life was completely destroyed, I had to start with that," she says.

"They taught me I had criminal thinking. I applied a criminal solution to every situation I got in. I learned how to counteract that.

"I surrendered. I surrendered the control that I thought I had, and I allowed other people to show me how to do something different."

She now has a job and what she thought would be impossible when she was an addict: a good relationship with the family she betrayed over and over again.

- Published26 April 2011