Rohingya minority group presses US on Burmese sanctions

- Published

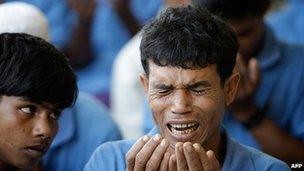

Last year, Indonesia picked up 130 starving, dehydrated Rohingyas from a boat in its waters

A prominent member of Burma's persecuted Rohingya Muslim minority has urged the US to limit any plan to lift sanctions against the country until the group's human rights can be guaranteed.

This week Dr Wakar Uddin, chairman of the Burmese Rohingya Association of North America, met officials of the US state department, members of the Senate foreign relations committee and members of the House of Representatives human rights commission to urge caution.

His plea comes in the wake of the election to parliament of dissident Aung San Suu Kyi, and as the US reconsiders some of its two-decades-old suite of sanctions against the South-East Asian country.

In the meetings, Dr Uddin also called for the release of Rohingya leaders imprisoned since the 2010 election that brought President Thein Sein to power.

"If somehow the Burmese government manage to get sanctions lifted and the Rohingya issue is not resolved, we are finished," Dr Uddin told the BBC.

"There is no hope because they will not revisit this. Whatever needs to be done about the Rohingya, it has to be done before the sanctions are lifted."

'Some positive steps'

In response, the US state department says it is concerned about human rights violations in ethnic minority areas, including restrictions and discrimination imposed against the Rohingya.

Dr Wakar Uddin is one of only a few hundred Rohingya refugees in the US

Secretary of State Hillary Clinton raised the issue during her meeting with Mr Thein in December.

In a statement, the US state department called on the Burmese government to take "concrete steps" to formalise the Rohingyas' legal status and to "immediately end human rights abuses" directed at them.

The United Nations describes the Rohingya as an ethnic, religious and linguistic minority from western Burma.

But the Burmese government says they are relatively recent migrants from the Indian sub-continent. As a result, the country's constitution does not include them among indigenous groups qualifying for citizenship.

The UN and other advocacy groups say their lack of legal status has led to systematic human rights abuses including rape, torture, abduction, forced labour, land confiscation. They are also forbidden to marry and to travel outside their villages without official permission.

The BBC approached the Burmese embassy in Washington DC for comment, but has received no response.

Hundreds of thousands of Rohingya fled to Bangladesh in 1978 and the early 1990s. Twenty-eight thousand are sheltered in UN refugee camps, but the majority live in informal camps where they suffer from malnutrition and have little access to healthcare and education.

The United Nations Refugee Agency describes their plight as one of the world's most enduring refugee crises.

'Carrot and stick'

Jennifer Quigley, of the US Campaign for Burma, an advocacy group, says: "The US and the international community need to make citizenship and the treatment of the Rohingya a benchmark for lifting sanctions.

"The US is giving too much too fast. It doesn't give any incentive to keep the reform process going."

While evidence of abuse is anecdotal and hard to verify because of restricted access to the region, Dr Uddin, a biologist at Pennsylvania State University, says his sources tell him that the Burmese government has stepped up oppressive action.

"The Rohingya situation - the human rights situation - has gotten worse since the election," he says.

But the state department says it has no "substantive evidence" the Burmese government has launched a co-ordinated crackdown against the Rohingya. According to a spokesman, some aid groups say conditions have even eased, with Rohingyas being granted more freedom of movement inside townships.

However, Dr Uddin fears the West is being distracted by apparent reforms elsewhere in Burma and wants an independent team of international observers to monitor the situation in Arakan State where the Rohingya live.

In January the government signed a ceasefire deal with Karen rebels who had waged a battle for greater autonomy for more than six decades. Western governments demand an end to the conflict before they will lift sanctions.

"The government is trying to show the West that they are dealing with the Karen and other groups by giving rights and making a truce," he said.

"But they are showing the carrot in one hand and the stick for us [the Rohingya] in the other. It's a distraction and a diversionary tactic."