Young migrants make perilous US-Mexico journey

- Published

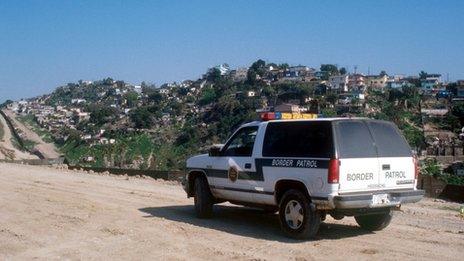

The number of unaccompanied minors making the journey into the US has risen sharply in recent months

Born in Nayarit, on Mexico's west coast, Daniel had planned for months to organise a trip to the US to find himself a job in construction.

He thought of taking a small boat up the coast from Tijuana to San Diego. But he got frightened and instead hired a coyote who took him across the Rio Grande by boat.

He eventually landed on the other side but was spotted by the border patrol, handcuffed and taken to a station to be interrogated. He was 16 years old.

Maria left Guatemala to head north: it took her weeks to make the perilous journey through Mexico, during which she encountered traffickers, smugglers and abusers.

She was escaping abuse and neglect from her own family and had been on her own from the age of 14, first as a domestic worker and then as a solo migrant.

US border agents caught her as soon as she crossed into their territory, and Maria ended up in a detention centre in Florida.

Experts say Maria and Daniel (their names have been changed to preserve their anonymity) are just two cases among many.

The number of unaccompanied, undocumented minors apprehended along the southern US border is at a record high, they say, and could nearly double in 2012 compared to 2011.

Custody or deportation

Between October 2011 and March 2012, a total of 5,252 minors were taken into custody after trying to get into the US illegally - a 93% increase from the same period in the previous year, according to the US Department of Health and Human Services. The department's Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR) handles the custody of undocumented minors caught in the border zone.

"There was a spike in the number of unaccompanied minors coming in. By the end of April, the number of apprehensions topped the mark of 6,000 and we estimate it will be around 8,000 before July," David Shirk, director of the Trans-Border Institute, University of San Diego, told the BBC.

"That is near the peak of 8,200 cases of unaccompanied minors detained in 2010 and well over the agency's estimate for the entire year," he said.

But experts say these figures only reflect part of the migration flow of unaccompanied minors.

"These cases are only of those who are apprehended and taken into the US legal system. But they do not count those who actually succeed in getting through or those who are deported right away, within hours of arriving into the US," Mr Shirk added.

When intercepted by the US authorities, unaccompanied children are first processed by the Department of Homeland Security and then turned over to the ORR.

They are allocated to shelters, where a search for a relative or guardian is carried out. If successful, the minor will be relocated to the custodian's house.

Both those who are found a suitable guardian and those who remain in shelters have to face immigration proceedings.

According to the Vera Institute of Justice - a non-partisan centre that has administered the federal government's Unaccompanied Children Program since 2005 - 40% of the children were identified as potentially eligible for some form of relief from removal.

Children from Guatemala make up the largest group of unaccompanied minors that the ORR deals with (35%), followed by those from El Salvador (25%) and Honduras (20%).

But most of the minors caught at or near the border are of Mexican origin. They account for over 80% of the flow, according to a report on migrant Mexican children from non-profit network Appleseed, published in 2011.

"Mexican kids get turned around right away at the border in almost all circumstances", said Betsy Cavendish, executive director of Appleseed.

In 2009, Customs and Border Protection (CBP) said they had caught 15,500 unaccompanied Mexicans under the age of 18, nearly all of whom were immediately repatriated.

"Kids from Central America may have a better access to counselling, to legal and social services, simply because they are taken into custody," Ms Cavendish told the BBC.

'Caging effect'

Experts are unable to pinpoint the reasons behind this exponential increase: more in-depth research needs to be done, they say, since answers from the children themselves during questioning have not changed enough to explain the phenomenon.

Experts say the reasons why children are migrating have not changed much in recent months

"Violence in their home countries, sexual abuse, social and economic adversity, the search for better job opportunities and family re-unifications are the most common reasons they give," said Michelle Abarca, a lawyer with Americans for Immigrants Justice, an organisation that provides pro-bono representation for children facing immigration proceedings.

But various factors have been suggested as drivers for the increased migration of unaccompanied minors.

Experts suspect that tightened security at the border has paradoxically increased the flow of undocumented children travelling alone.

"Seasonal migrants who used to come to work and then returned to their home countries, especially those employed in agriculture, now often decide to stay: it has become increasingly dangerous and costly to cross back and forth," said Mr Shirk.

Experts call it the "caging effect": law enforcement policies on the border area have "locked" migrants in the US - mostly men who come on their own and leave families behind - and their children often have to travel solo to rejoin.

Also, the number of migrant women is on the increase, says Ms Cavendish, "and those women are likely to be followed by their children if they were left behind".

Social unrest and spiralling waves of crime and violence in Central America could also foster the migration trend.

A newly released World Bank report highlights three main drivers for crime in Central American countries: drug trafficking, youth violence and gangs, and availability of firearms.

As a result, a region the size of Spain registered 40 homicides a day, while Spain has 336 a year.

"Research shows that the number of Central American children who are migrating is on the rise and we may attribute that to the increased violence in the region", said Betsy Cavendish.

- Published25 January 2012

- Published17 December 2011