Kehinde Wiley: Paintings of a moment that never occurred

- Published

The first time I saw a painting by Kehinde Wiley, external I was entranced by his vivid, hyper-real portraits. They hit you like a punch and take your breath away because they're funny and mocking and strong, with a message about power in the past and in the future.

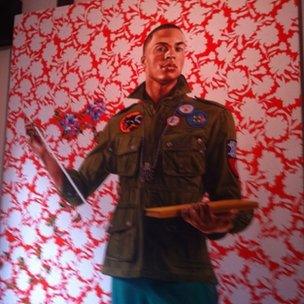

His speciality is painting modern African Americans in street clothes in the poses of the rich and powerful made famous in classic European painting.

A smaller man than many of those he paints, he's reflective and self-possessed.

"By using subjects who come from underserved communities, creating a global conversation around who has power, who deserves to be seen in the great museums throughout the world, I don't think I'm throwing any systems," he says.

"I think I'm simply pointing to moments of beauty, moments I definitely recognise as being worthy of being celebrated. I think in those small moments, that's where art works at its best.

"It's not about creating grand sweeping political narratives, it's about finding quiet moments of beauty in the world, and for me, those moments happen to look like me."

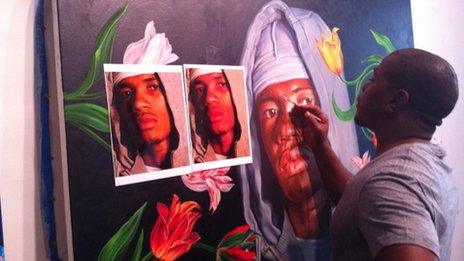

He describes his work in striking terms: "My style is in the 21st Century. If you look at the process it goes from photography, through photoshop where certain features are heightened, elements of the photo are diminished."

"There is no sense of truth when you're looking at the painting, or the photo, or that moment when the photo was first taken. So in that sense, these are paintings of a moment that never really occurred, these are moments of hyper-reality."

'Energy of streets'

He's just back from a gruelling tour of Africa, where he wants to set up a new base.

His main studio is in Beijing, but I catch up with him in New York where the streets outside are filled with the faces of those who first populated his paintings.

He films the first encounters with his subjects and plays me some of this footage. Spotting potential is easy, selling the idea that someone should become an art model is not.

The streetwise suspicion of those he accosts can be intense, but some are clearly intrigued by his unexpected proposal.

"I'm looking for a sense of self-possession, a type of swagger, a sense of grace in the world. It's hard to say exactly what that is, you know it when you see it," he says.

"I think it's important to allow for the energy of the streets, the absolute chance to determine who gets to be in these paintings.

"Unlike the paintings of the celebrated - the powerful in the past - these are paintings of people who happened to be in the streets that day, minding their own business, trying to get to the subway, and an artist stops them and pleads with them to engage in the process.

"I usually bring books and examples of my work because most people say 'No', but I think that the people who do say 'Yes' do that because they see promise and potential in the work, there's a little bit of curiosity there."

Cultural shift

Those he chooses and agree to help are drawn further into the creative process - they are not merely passive faces and bodies.

"The next step is to invite people to my studio whereupon we go through a series of our history books.

"Each model is looking at portraits from the past and imagining how they would fit into that narrative and so I allow them to chose how they want to pose, how they want feature in the creation of this image-making."

Since I first discovered one of Kehde's paintings in a Washington gallery, I have been seeking out other examples of his work. But an obvious thought struck me at once.

While Kehinde specialises in putting the traditionally powerless in poses of the powerful, reality has provided an ironic counter point - a black man is, in fact, one of the most powerful men in the world, more powerful than Napoleon or the Duc d'Arenberg, external, the subjects of the originals he draws on.

"The reality of Barack Obama being the president of the United States - quite possibly the most powerful nation in the world - means that the image of power is completely new for an entire generation of not only black American kids, but every population group in this nation.

"The way that we're coded for power has been recontextualised in terms of race. Now there are children who are four or five who would have known only a black man at the seat of power in this nation. It's an important social message.

"There is a cultural shift in the nation that says possibility is not necessary impacted or determined wholly by the colour of your skin.

"That said, this society has a long way to go, and - as we go through this election cycle - there are echoes of racism that continue to enter and occupy the American imagination.

"There is - and always will be - the legacy of chattel slavery in this nation, an obsession with racial and gender differencec, but I think that, at its best, this nation is capable of creating standards for itself and reaching towards those standards.

"Obama stands as a signal that this nation will continue to redefine what it means to push beyond the borders of what's possible."

Troubling times

He says Mr Obama sends a signal far beyond the US.

"As an artist who travels the world and interacts with other artists throughout the world community, I've constantly been asked about Obama.

"Many people want to know how black Americans feel about him being in this position of power.

"And I think, clearly, there's a great amount of excitement and elation, but what I'm most fascinated with is their response to the fact that a black man is in charge - specifically the response of international artists.

"What I find is that so many artists, thinkers and writers have a new respect for America. They have a sense in that America has redeemed its brand.

"For so long the build-up to the first and second Gulf Wars, during the turmoil and strife that pervades Afghanistan currently, the American brand came under great political and cultural scrutiny. And for so many creative individuals, the trust - that social pact America had with itself and with the world - was tarnished.

"With the decision to bring Obama into the leadership of this nation, America as a group decided to say 'Yes' to a different track."

Although we don't talk about it, his background is quite similar to Mr Obama's. Both were brought up by single mothers, who were fascinated by anthropology, and whose fathers were Africans who returned home.

It was his mother who encouraged his interest in art as a child.

"I became engaged with the old master paintings and the tradition of painting in Europe as a child. My mother sent me to art school at the age of 11 as a way of getting me off the violent city streets of south-central Los Angeles.

"During the 1980s, south-central Los Angeles was going through a very troubling time. There would often be shootouts in the streets, and you would want to be home, somewhere safe, while bullets were flying.

"This was not a beautiful time for the inner city in Los Angeles.

"My art school had a number of classes that would teach us the foundations of painting, but part of that had to do with going to the museums and actually looking at real works.

"So it was not about just simply looking at a bowl of fruit and copying a bowl of fruit, it was looking at some of the great Dutch masters who created still lives and fetishised that moment.

"It was more than just that idea of making the still world into a plastic form, it was actually that spectacle in real time, in the real world, in front of me."

I ask him whether he would like to do a portrait of the president.

"I think it would be really interesting to paint Obama," he says. "I've done several studies in the past, I've sort of worked out different strategies about how that would be, but it's a very curious possibility. We'll see where that goes."