US election: How can politicians bring back jobs from China?

- Published

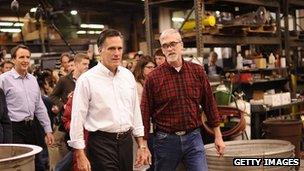

Factory visits are a staple of US campaigns; Romney visited one in New Hampshire in January

Presidential candidates Barack Obama and Mitt Romney pledge to create jobs, and that will involve bringing home manufacturing jobs from China. But do politicians even offer American businesses what they need to bring jobs back?

Voters in the swing state of New Hampshire have an extra interest in hearing more details about Mr Romney and Mr Obama's jobs plans.

New Hampshire earned the dubious distinction of losing more jobs to China, per capita, than any other state from 2001-11, according to a new study from the Economic Policy Institute.

Companies like Watts Water Technology helped the state secure that spot.

The company had been making water control valves at a factory in the town of Franklin since 1959, but the company began shifting jobs to China a dozen years ago.

The company didn't entirely shut things down in New Hampshire, and today, the Franklin factory is once again bustling.

That's because it has begun to make sense to bring some jobs back home, says operations manager Ken Sargent.

"The cost of labour in China is constantly going up, the fuel to get [the product] here is constantly going up," he says. "A lot of the benefits of doing business in China have deteriorated."

And operations are becoming more streamlined in New Hampshire, he says, "which makes it a lot more cost effective to bring the work back to the states".

Markets and customers

And Mr Sargent is just happy to be back home.

"In China, I really didn't know what to expect," he says. I had translators for many of my meetings.

"The cultural barrier is significant. It's much harder for a manager to come from the US and not offend the Chinese people."

Mr Sargent says Watts Water has brought back more than 125 jobs, about two-thirds of what they originally moved to China.

Tyler Stone, the company's director of operations, says government incentives can influence the decision to relocate jobs, "but it's usually never the driver".

"The driver is really around how we serve our markets and our customers," Mr Stone says.

Though politicians may be quick to take credit for bringing manufacturing jobs back from China, "it's all baloney", says Richard D'Aveni, professor of strategy at Dartmouth College's Tuck School of Business.

US 'disadvantage'

That's not to say that government shouldn't try to help businesses compete with China.

Most of Hypertherm's employees work in New Hampshire

The US is fighting and losing a new economic Cold War with China, he says, in part because the country has failed to adapt.

"Our form of capitalism is at a disadvantage compared to state capitalism," says Mr D'Aveni.

"And so far, what we've tried to do is to level the playing field by getting the Chinese to act like us," by invoking World Trade Organization free trade rules and pressuring Beijing to curtail currency manipulation.

That might stop China's economic juggernaut in the short-term, but Mr D'Aveni says it is a losing strategy for the long term.

And what voters often hear are promises to restore what we've lost, says Dennis Delay, an economist with the New Hampshire Center for Public Policy Studies. That does voters little good.

"If you look at the manufacturing jobs that have been lost, in a very real sense those jobs have gone and probably will never come back," he says.

"They've gone to China or to Mexico, or to other countries with lower labour costs or lower natural resource costs.

"But in part, they've been replaced by automation, by technological change."

Tax breaks and subsidy programmes can create a short-term boost, he says. But to promote long-term economic growth, policymakers need to focus on educating the workforce.

"Where New Hampshire competes is in producing high value-added products that require a significantly trained workforce," he says.

"And that's a very difficult combination for other countries to be able to match."

'Deep tradition'

To see that formula in action, I ride up the road to the town of Hanover, where Hypertherm Inc makes equipment used around the world to cut steel and aluminium.

And Obama visited a Wisconsin factory last year

Most of Hypertherm's 1,300 employees work in New Hampshire, and the company exports 20% of its product to China.

The company has decided not to move the factory to China, even though "there's nothing that technically requires it to be here in the US", says president Evan Smith.

He compares his firm to successful German manufacturers who have invested locally and for the long term rather than chase short-term profits.

Hypertherm has spent a couple of million dollars on a training institute to ensure a steady stream of skilled machinists. The states of Vermont and New Hampshire and the federal government in Washington helped.

That is the type of government support many in the state call for. The presidential candidates do address workforce training in their platforms, but most of their economic arguments focus on taxes.

Mr Romney promises lower business taxes, while Mr Obama says he'll end tax breaks for companies that outsource American jobs.

I asked Evan Smith at Hypertherm how much he considers taxes when deciding where to manufacture.

"I can't think of a single strategy meeting that we've had where that's come up," he says.

Listen to more on this story at PRI's The World, external, a co-production of the BBC World Service, Public Radio International, and WGBH in Boston