Mark Mardell: Good politics reads for the weekend

- Published

- comments

Do debates make the presidential race anymore? A raft of US presidential politics and other must-reads from Mark Mardell

In the spirit of the BBC Magazine's Seven of the Week's Best Reads, I continue my weekly list of must-reads for the second time.

As with all links and tweets, I hardly need to say that I am not endorsing any views contained within my picks. But I am saying they are worth a read.

Debate night

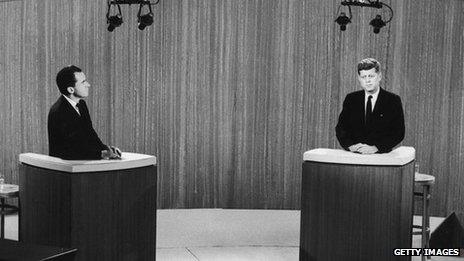

Barring unexpected asteroid strikes, next week will be dominated by the first debate between Mitt Romney and Barack Obama.

You can hear me discuss how much debates matter on the BBC's Today programme, external on Wednesday morning, but in GQ, Robert Draper argues they will determine the outcome of the election, external.

I am not sure I agree with that, but he's got some interesting insights into the two men's debating history and punctures some myths about debates of the past.

What makes a good president?

I've covered loads of election campaigns and they are nearly always enthralling and revealing, at least to political junkies. But Slate poses a vital question, external, which is not often asked enough: whether campaigns are a good way of choosing our leaders.

As John Dickerson writes: "If good campaigners made good presidents, we'd have a constant string of successes. Most sitting presidents, almost by definition, have been skilled on the campaign trail. Yet the talents do not necessarily convey."

He suggests that perhaps presidents should be chosen as big companies would pick their CEOs - by rigorous job interviews asking questions about how they would handle key aspects of the job, including political skills, management ability, persuasiveness and temperament.

He's asking people to come up with their own ideas. It's a fascinating start to a series I will be following closely.

The cost of stopping Iran

My next pick is perhaps not a great read in the classic sense, but it is an important one, in a week in which the Israeli prime minister seemed to move back the deadline for when he thinks there should be an attack on Iran. The World Affairs Council has published a report, external by bipartisan experts on what impact a military attack on Iran would have on the country's nuclear programme.

They are explicit that they are not trying to make a political or moral judgment, but attempting to set out the facts, even if they are hard to come by.

Their conclusion is that an "operation carried out to near perfection" by the US would set back the programme four years, and by Israel alone, two years.

They say to stop Iran ever getting the bomb (by producing regime change or something similar) would mean an "air and sea war over a prolonged period of time, likely several years".

"In order to fulfil any of the more ambitious objectives suggested above, an even greater commitment of force, including troops on the ground, would be required to occupy all or part of the country."

They conclude that this would cost more than the Iraq and Afghanistan operations combined.

The making of Richard Nixon

But head and shoulders above anything else I have read in the last few days is about a moment of TV and political history,, external by Professor Lee Huebner, a former Nixon speech writer.

Sixty years on from Nixon's Checkers speech, he vividly tells the tale of how the young politician picked as Eisenhower's vice-president saved his political life with an emotional broadcast after being accused of having a seedy campaign fund.

He makes a convincing case that this TV broadcast changed communications in American politics, bringing a politician's family to the centre of the screen, that it made Mr Nixon a star and sowed the seeds of future disaster.

But most interesting is his argument that it was the beginning of a cultural divide still hugely important today - the right's populist attack on elitism.

"He accomplished this goal by identifying himself not only with the circumstances of 'ordinary' Americans, but also with their resentments of the fancy and facile elite," Mr Huebner writes.

"The attacks on him, in this context, became yet another symbol of privileged arrogance. And the apparent normalcy of his life convinced millions that he was truly 'one of us.'"

And it heightened the hostility of those who were attacking him.

"The 'Checkers speech' would account, in significant measure, for a visceral sense of distaste and distrust among many of Nixon's permanent critics, forever suspicious of what they saw as his 'maudlin' or 'corny' appeals."

A fascinating read - hope you enjoy this and the other picks.

- Published21 September 2012