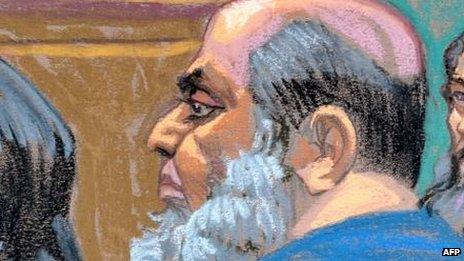

Meeting Khaled al-Fawwaz - Bin Laden's man in London

- Published

Khaled al-Fawwaz operated openly in London as a media officer for Bin Laden

The Saudi terror suspect set to appear on Tuesday before a US judge - who will oversee his trial for complicity in mass murder - once strode confidently into a central London hotel and extended an invitation to the BBC to come and interview his boss, Osama Bin Laden, in his Afghan hideout.

On a warm August day in 1996, I was introduced to al-Qaeda's de facto spokesman in London, Khaled al-Fawwaz, one of the five terror suspects extradited from Britain to the US last weekend.

Along with his co-defendant, Adel Abdul Bary, he stands accused of complicity in al-Qaeda's 1998 bombings of the US embassies in Nairobi and Dar Es Salaam that killed 224 people. Both men have entered a not guilty plea in New York's federal court.

Before his arrest in 1998 and his subsequent 14-year detention in UK jails pending extradition, Mr al-Fawwaz operated openly in London as a media officer for Bin Laden, distributing faxes and pronouncements in the name of the Advice and Reformation Committee (ARC), set up in 1994.

He is also accused of acting as a liaison for al-Qaeda cells in East Africa.

Scowl

It has been reported that during the 1990s he was in regular contact with Britain's domestic intelligence service, MI5, an arrangement that ended in disappointment for both parties.

MI5 appeared to be hoping that Mr al-Fawwaz would provide them with an insight into Islamist extremists living in Britain. Mr al-Fawwaz was under the impression that his contacts with the Security Service would keep him out of trouble.

Al-Fawwaz is accused of complicity in the 1998 bombing of the US embassy in Dar Es Salaam

But after the double bombing of US embassies in East Africa in 1998 he was arrested at Washington's request and has spent all this time fighting extradition to the US.

So what to make of the man described at the time as Osama Bin Laden's PR rep in London?

My colleague, Nick Pelham, from BBC Arabic, had already been in touch with Mr al-Fawwaz and set up the meeting in the palm court tea room of the Waldorf Astoria hotel, in the heart of London's theatreland.

That summer of 1996 was already a time of tension in the wider Middle East. Two months earlier a massive truck bomb had gone off at a US air force barracks in Dhahran, Saudi Arabia, killing 19 US airmen.

Bin Laden had expressed his approval but did not say he was behind it. He had recently moved his base from Sudan - where the CIA was getting uncomfortably close to him - to the mountains of eastern Afghanistan, beyond their reach.

Minutes after we arrived at the Waldorf, a tall, powerfully built man strode in, wearing the traditional white thaub robe of Saudi Arabia.

I noticed the dark brown mark on his forehead that comes from frequent prostration in prayer, an indication of a very devout Muslim.

Mr al-Fawwaz scowled at the hotel's entertainment: a pale girl in a dress with bare arms playing the harp, rather beautifully, I thought.

He joined us in a quiet corner of the room and cut straight to the chase.

"Sheikh Abu Abdullah is ready to see you," he said, using the colloquial term Osama Bin Laden's friends and followers addressed him by.

"He has chosen the BBC to give his first TV interview to."

Bin Laden had already given a print interview before leaving Sudan but, even back then, a full five years before his post 9/11 videos started popping up on al-Jazeera, he could appreciate the power of the media and particularly television.

Game-changing offensive

My colleague and I exchanged glances. We were both thinking the same thing: would we be safe? Only days earlier Bin Laden and al-Qaeda had announced their "Declaration of war against the Americans occupying the Land of the Two Holy Places".

Mr al-Fawwaz looked almost apologetic. "Ah yes," he said sheepishly, "I disagreed with the sheikh about the timing of this announcement, but don't worry, he will vouch for your safety, you will be his guests and enjoy his protection."

This was one of the curious ironies of the whole Bin Laden phenomenon.

A man who could commission mass murder and destruction on an epic scale was also a man of his word when it came to promises of protection. In later months many Western journalists were to beat a path to his Afghan door and return home unharmed.

Many Western journalists beat a path to Bin Laden's Afghan door

We got down to details. Bin Laden did not want us to travel through Pakistan.

"You will be followed by the ISI (Pakistani military intelligence)," said Mr al-Fawwaz.

Instead, he said, we were to fly to Delhi, then catch a flight to Jalalabad, overflying Pakistan without landing.

At Jalalabad airport we would be met and taken up into the mountains of Nangarhar province to meet Sheikh Abu Abdullah and conduct his first TV interview.

It promised to be a BBC scoop and over the next few days I went into overdrive, organising Afghan visas, flights, inoculations and a cameraman.

And then suddenly, two days before we were due to fly, the Taliban launched a game-changing offensive, advancing rapidly out of their southern Afghan stronghold towards the capital, Kabul.

The situation in Afghanistan was fluid and unstable.

"Tell the BBC to wait till things settle down," Bin Laden said to Mr al-Fawwaz in London.

But we had missed our moment. In the ensuing confusion other networks nipped in, did their interviews and made headlines.

Osama Bin Laden lasted another five years in his Afghan refuge before fleeing to Pakistan after the 9/11 attacks.

Khaled al-Fawwaz remained free for only two more years and I never saw him again.