Sandy and the Jersey Shore: The struggles of Ortley Beach

- Published

The ever-growing piles of rubbish outside every home in Ortley Beach only hint at the sadness of the owners inside.

There is a lot of wooden furniture, much of it clearly carved and crafted decades ago, and sofas upholstered in patterns of the past. There are mattresses and clothes left sodden by water.

But there are also leather footballs, children's bicycles, and vintage LPs; there are gas-fired BBQs, refrigerators and plastic flowers.

As good Italian home-makers, John and Merlinda Berish even had six months' worth of home-cooked meals in their freezer. No longer.

Sandy's salty floodwater and its deadly ally, a creeping mould, have spared little.

Instead of personal possessions the Berishes now have a rogue home sitting outside the front porch, a beachside bungalow that has come to rest a full quarter of a mile from its usual spot.

Sandy tore the house from its foundations in Beier Avenue and sent it careering up 3rd Avenue, where it eventually slammed into the Berishes' property and came to a halt. It's still there, weeks later.

"It hit my house pretty good," says John Berish, 75. "I wish they'd get it out of here now. It's an eyesore.

"Everything you see in most houses up and down the street is destroyed. You name it, it's gone."

John and Merlinda Berish's home white wooden home was hit by the corner of the rogue house

He looks out over his front porch and surveys his belongings.

"Everything you have personally in your life is now going out in the garbage cans."

The Berishes' experience is entirely typical of the new reality in Ortley Beach. One month on from Sandy's inundation, it's not that Ortley Beach is yet to recover; the problem is that it has barely begun.

The barrier island community was especially vulnerable to a storm like Sandy, which pushed great swells of ocean towards the coast, breaching protective dunes and flooding virtually every home.

While Ortley Beach is often referred to as "ground zero", other Jersey Shore communities were also badly hit: Seaside Heights, Lavallette, Normandy and Mantoloking on Ortley's island strip; on Long Beach Island and in Atlantic City to the south.

The governors of New York and New Jersey states have now asked for almost $80bn (£50bn) in federal funding for disaster relief and future flood prevention. New Jersey's $37bn request is bigger than the state's entire annual budget.

In Ortley Beach, it is hard to overstate the chaos and sadness the storm has left behind.

Although no-one died here, tales of loss are on every street corner and in most of the homes in between.

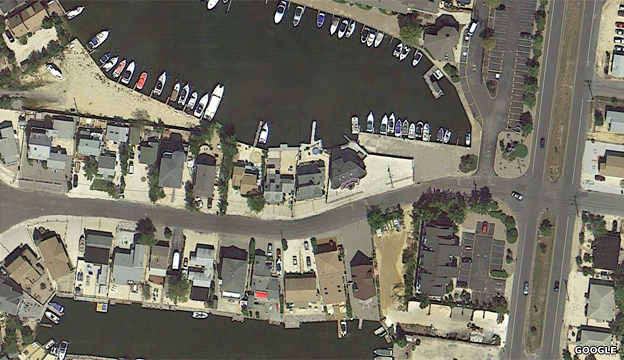

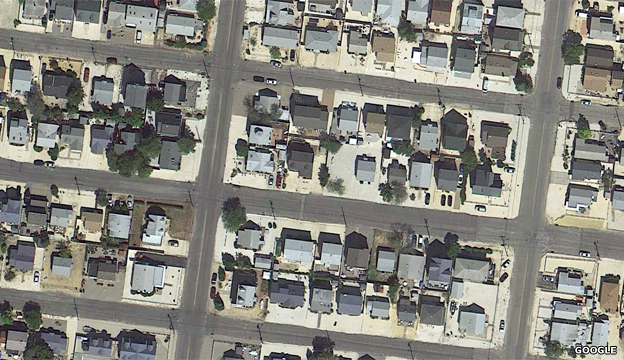

Ortley Beach on the New Jersey Shore took the full force of Sandy

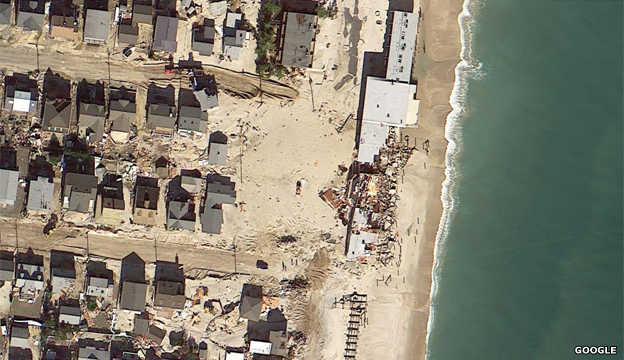

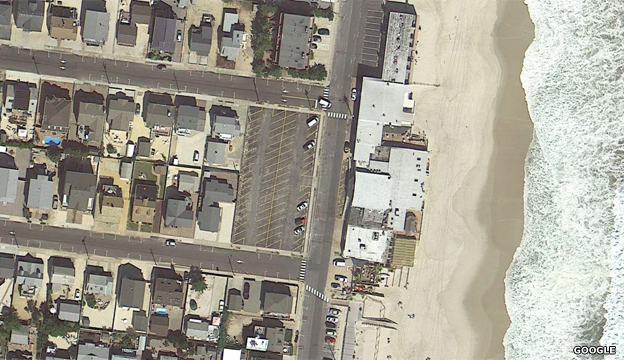

Beachfront homes on Ocean Avenue were washed away by the storm

The Ortley Cove side of the community was also hit

The famous Surf Club and boardwalk were reduced to timber

A house moved from several streets away to Washington Avenue

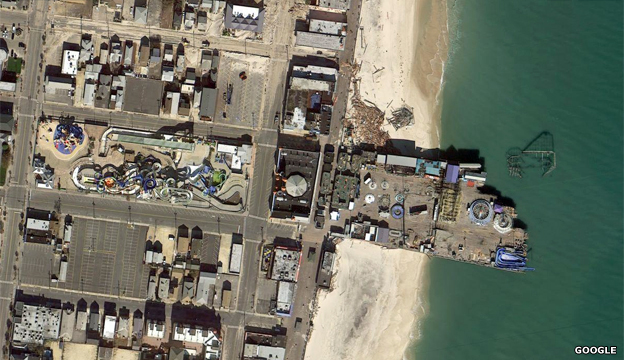

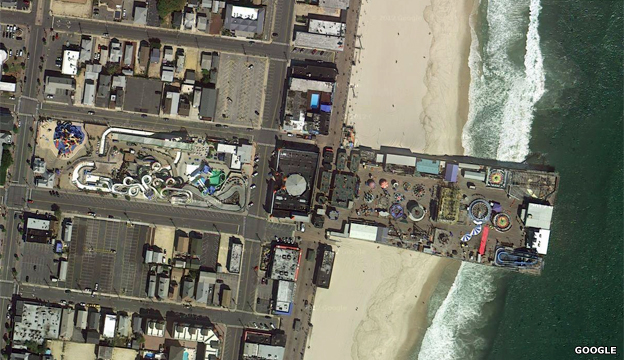

The funfair in the next town, Seaside Heights, suffered too

Residents and homeowners gained regular access to the island only last weekend, after Thanksgiving. One-third of Ortley Beach is now open each day, albeit with access controlled by police.

There is no power, no gas, few toilets, no sewerage, no phone service, no shops and no restaurants. No-one sleeps in the town at night.

"They're all victims, and our goal is to help them one victim at a time," says Mike Mastronardy, chief of police for Toms River Township, which includes Ortley Beach.

As the water receded, Mastronardy and the Toms River council kept residents off the island, away from their ruined homes, until emergency infrastructure repairs made Ortley Beach safe to enter.

It was not a universally popular policy, and public discontent grew as impatient residents clamoured to see their homes and assess the damage.

Those who did make it in found the town in ruins. The beach had been eviscerated, with 8ft-high (2.4m) protective dunes simply washed away. Instead, streets within two blocks of the water were filled with 2-3ft of sand.

Homes, boats and cars were strewn around, power lines were down, sinkholes appeared, and many buildings were unsafe.

"It really wasn't a good idea to go back there," Toms River council member George Whitman Jr says.

"I think once residents were able to get over to the island after it was cleaned up they got a full appreciation of the damage over there."

Only by visiting Ortley Beach itself is it possible to understand what Whitman means.

At its northern tip is a towering mountain of sand, reclaimed from the streets and corralled on top of what was once a popular pier.

From there, sweeping south, much of what remains is a withered mess.

The Surf Club, a Jersey Shore institution, now lies in ruins, and the wreckage of Ortley Beach's boardwalk runs both ways along the beach, meandering south towards Seaside Heights and its now-famous rollercoaster-in-the-ocean.

Before the storm, beachside dunes higher than the boardwalk protected the walkway - and the road and homes beyond - from storm-tossed seas.

But there are no dunes anymore. There is no tarmac road either, just an expanded and flattened beach stretching from the sea to the streets.

The houses ranged along Ocean Avenue are shattered, broken or simply not there anymore. The road that once ran parallel to the boardwalk is now twisted, broken and buckled.

There was no rain, and little wind, as Sandy closed in on the Jersey Shore on 29 October. But water had already seeped into the streets by the time the clock struck noon. As night fell, Ortley Beach was already flooded.

"I went up to the ocean and they said the storm was about 500 miles away, and it had already breached the dunes and damaged oceanfront homes," says Frank Mazzo, a local builder who defied an evacuation order as the waters rose.

"That was about noon. By eight o'clock, eight-thirty, the water just rose about 2ft. By nine we were really in the thick of it."

Mazzo's sturdy, modern house - by the bay almost half a mile away - was barely damaged. Water flooded his garage, but most of his property is built on sturdy concrete pillars, and no structural damage was done.

"I built the house to withstand these things. But who knew the first hurricane we faced would be the 100-year storm, or the 500-year storm?"

Mazzo's neighbours were not so fortunate. To his right, Joanna Anselmo's neat, pink summer home - bought by her family in 1948 - is at least still standing. But it now perches precariously over a watery pit.

"It's very, very surreal," she says. "I keep waking up and thinking it didn't happen."

The house to Frank Mazzo's left, at 2029 Bay Boulevard, is listing oddly, its front aspect plunging forward into the same hole that scuppered the Anselmo home.

"The house is cracked in half at the back, I got a four foot pit around the back of my house, and my shed is nearly in the bay," says Bill Carroll, who has lived in Ortley Beach for 50 years.

John Berish says he has doubts about rebuilding. "It will never be the same again"

"Pretty much, we lost everything here. We're coming out with nothing."

But if Ortley Beach is sad, it is not universally depressed.

Across the road, Karen and Rick Vail are literally taking a breather. Clad in white all-in-one Tyvek "disaster suits", they sit by their car and remove the face masks protecting them from prolonged exposure to mould spores.

The Vails are clearing Karen's mother's home, salvaging what they can. But she worries that many people might suffer at the hands of insurance companies.

Homeowner insurance generally does not cover flood damage, and many people were either unwilling to buy flood insurance or unable to get coverage.

"Right now everybody is worrying about the immediate, rather than when the insurance company starts paying off later," she says.

"People have a tendency to get angry as they get removed from something. I think the fallout from the insurance is still to come."

But she is optimistic, too: "Coming back in and seeing all the people rebuilding, instead of making me sad it's making me more hopeful."

Back on the beach, Police Chief Mike Mastronardy looks around the splintered landscape and sees a recovery already under way.

"You should have seen it two days after the storm hit," he says.

"We'll be in business this summer. You want to get a beach patch?"